The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

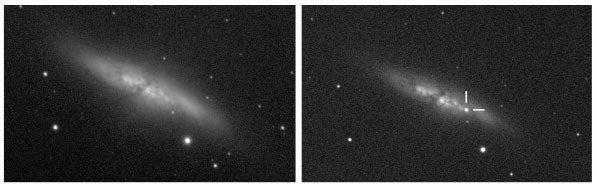

White dwarf explodes in the galaxy next door: Type 1a supernova spotted in Galaxy M82

The stellar explosion is the closest to be spotted since 1987 and will provide a 'galactic yardstick' for astronomers judging distances across the universe

Exploding stars rarely make astronomers blink. Not because they’re incredibly jaded but simply because supernovae are a fairly common event. However, when a star explodes only 11.4 million light years away (practically next door in astronomical terms) they really sit up and take notice.

This is the case with supernova M82, a stellar explosion so close to Earth that it could soon be visible with binoculars. Named after its nearest galaxy, supernova M82 looks to be the brightest of its kind observed since 1987, and is expected to increase in brightness of the next two weeks.

Supernovae occur when a star – or more than one stars – explode, emitting in a matter of weeks as much energy as the Sun is expected to emit over its entire lifespan (around 10 billion years - 4.6 billion of which it’s gone through already).

There has been some contention over who was the first to spot the new supernova, with a team of amateur Russian astronomers in Blagoveshchensk and an astronomer from University College London, Dr Steve Fossey, both claiming to have been first on the scene.

After Fossey spotted the supernova on 21 January he emailed colleagues at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena. There, graduate student Yi Cao undertook a spectral analysis of the object, confirming that it was a supernova and identifying it as a type Ia event.

"This particular galaxy is unusual and it's pretty close by to use so close, nearby supernovae of this type happen probably once every few decades," said Dr Fossey to the Today programme, explaining that the scientific community would have to now muster various telescopes to examine the supernova.

"This is a time critical opportunity. The object will remain bright for several weeks - and we need to conduct an autopsy on the patient to find out how it died."

This is especially exciting for astronomers as the 1987 supernova was a type II. Type I supernovas occur through a process known as ‘thermal runaway’ between a binary system (a pair of stars) whilst type IIs are triggered by the core collapse of a single, massive star.

Type Ia supernovae – as this event is suspected to be – begin with a pair of stars orbiting one another. At least one of the pair will be a white dwarf (the dense remnant of a star the size of our own Sun after it has exhausted all its nuclear fuel) whilst the other will usually be a red giant.

The denser white dwarf will then begin pulling matter away from its larger neighbour, and when it has absorbed enough nuclear fusion will reignite inside its core and it will explode.

Type 1a supernovae are particularly useful for astronomers as their variations in brightness follow a well-established pattern. This allows them to be used as ‘standard candles’ – objects of known luminosity that allow distances to be judged on the cosmic scale.

Because galaxy M82 (also known as the Cigar Galaxy) is so close to us, astronomers have plenty of pictures of the region prior to the supernova’s appearance and have already begun comparing these images, sifting through the galactic dust to find out more about how supernovae create different elements.

As Shri Kulkarni, an astronomer at the California Institute of Technology, told the journal Nature: “Dust has its own charms.”

More space news:

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks