Trillions of flies can't be all that bad

They spread disease, damage crops and don't mind eating decomposing bodies... but is having trillions of flies buzzing around the planet such a bad thing?

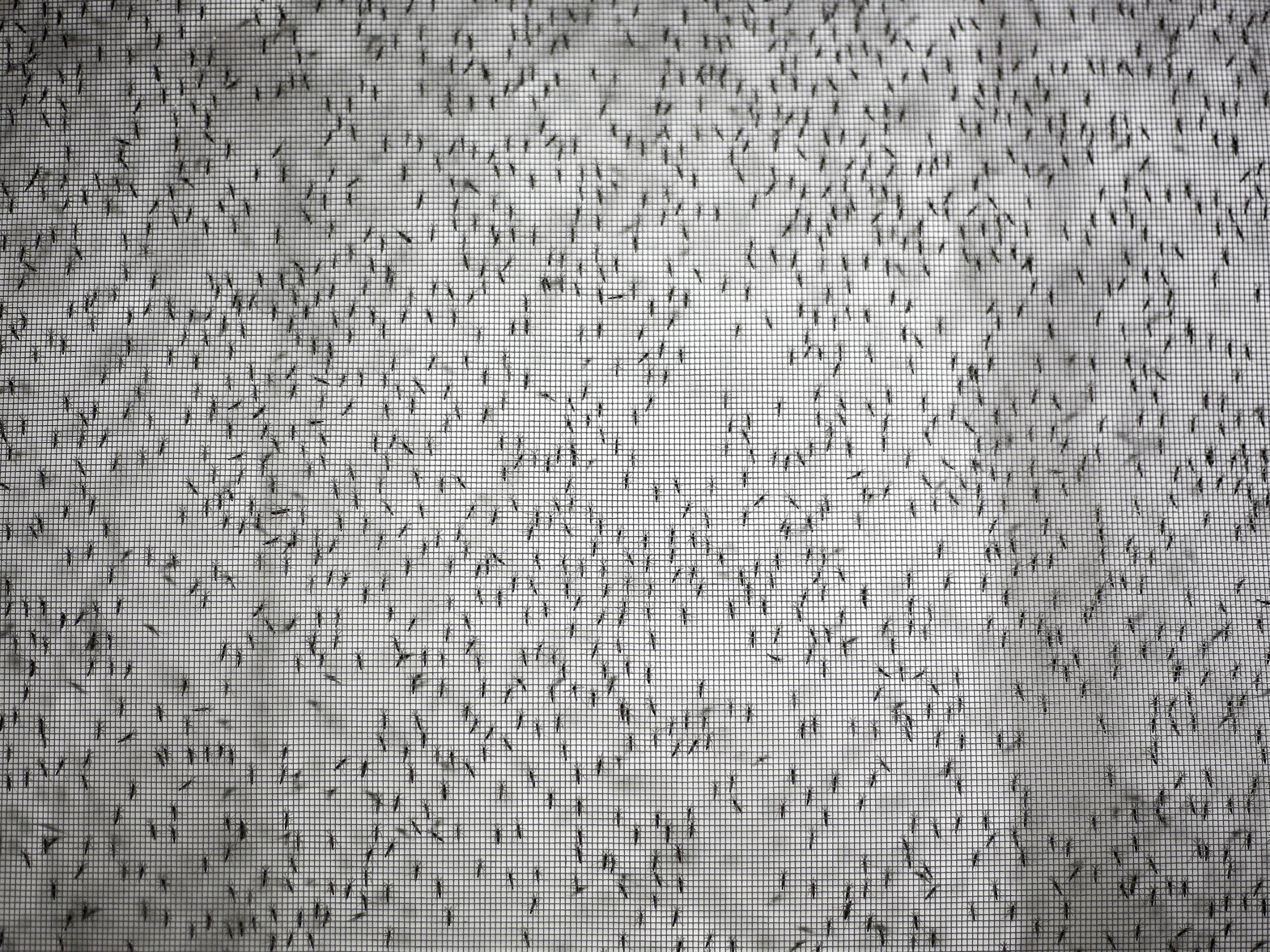

For each person on Earth, there are 17 million flies. They pollinate plants, consume decomposing bodies, eat the sludge in your drainpipes, damage crops, spread disease, kill spiders, hunt dragonflies.

Some have even lost their wings so as to live exclusively on bat blood, spending their lives scuttling about the fur of their hosts, leaving only to give birth to a single larva – usually.

“That’s why I love them. They do everything. They get everywhere. They’re noisy. And they love having sex,” said Erica McAlister, a curator of Diptera – flies, to the rest of us – at the Museum of Natural History in London.

McAlister has captured her affection for the Diptera in The Secret Life of Flies: a short, rich book, by turns informative and humorous – both a hymn of praise to her favourite creatures and a gleeful attempt to give readers the willies.

Her book is also the source of the 17 million number, which, she pointed out, is just an estimate.

Like other fly writers before her, McAlister has more than fun in mind. She wants to remind the world at large of the importance of flies to humanity, and to the planet. They are not just something to swat.

Without them, to take just one example, there would be no chocolate. McAlister herself hates chocolate, but she is fond of the kind of flies that pollinate the cacao plant: a variety of biting midge. The midges are tiny, mostly blood-feeding insects, but the chocolate midges like nectar and carry pollen from one plant to another.

Biting midges are, in fact, part of McAlister’s specialty. She is fond of all flies, but focuses on those that are included in the lower Diptera, which include mosquitoes, black flies and, as she puts it, “everything that’s bitey, stabby, nasty”.

Her life among flies involves both museum work and field research. For her, this is a dream job. She recalled the first time she went behind the scenes at the museum, as a student, before she actually worked there.

“I’d been let into a building that had 34 million insects. I said, ‘Oh hello, I quite like you.'”

McAlister’s fascination began in childhood. “I used to catch the fleas off the cats,” she said, inspecting them with a microscope her parents had given her. But she soon gravitated toward more gruesome insects.

Decomposing carcasses of small creatures, also courtesy of the cats, were treasure troves of maggots, which she still delights in. “I quite like the darker side of nature,” she said, just before discussing the lives of spider-killing flies.

The larvae “hurl themselves at spiders” in order to land on them and burrow into the abdomen. They then eat the spider from the inside out. But if the spiders are immature, the larvae may go to sleep for a few years until the spider grows into a bigger meal.

Many flies do an enormous service for us and the planet by cleaning up all sorts of the biological world’s detritus, from dead wood to the slime in drainpipes. Drain flies, or sewer gnats, are actually cleaning up human mess.

Occasionally, however, they may have a population boom that sends the adults into the air, which is annoying; if the bodies disintegrate into tiny particles in the air, they are potentially harmful to human health.

And, of course, there are the flies that feed on dead bodies – the 1,100 species of blow flies, favourites of forensic detective shows. The maggots of these flies, like the very attractive bluebottle larva, devour corpses of mice and men and everything else.

Knowledge of which species lay eggs at which stages of decomposition can help determine how long ago a person turned into a body. (If it’s Tuesday, it must be a bluebottle.)

There are 160,000 known species of fly, and entomologists can only guess at the number we do not know – it is somewhere between hundreds of thousands and millions.

Within science, flies are one of the great subjects of laboratory study. Or rather, the fly: Drosophila melanogaster, commonly known as the fruit fly – although McAlister points out it actually belongs to a group called the vinegar flies.

They are easy to work with and share the same basic DNA as all life. Historically, they have provided much of the foundation for modern genetics. And now they may provide deep insights into neuroscience and other fields.

Scientists at the Salk Institute have reported that their studies of how the fly brain works can improve internet search engines. At the Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s Janelia Research Institute in Virginia, the search is on to develop a wiring diagram of the fly brain, and then figure out in the greatest detail how they think.

And they do think, according to Vivek Jayaraman, who runs a lab there, in the sense that flies do not just react instinctively. Their brains make decisions based on several different inputs – smell, memory, hunger and fear, for instance. And that whole process is what he hopes to decipher, neuron by neuron. “You can go end to end, potentially, in the fly,” he said.

McAlister said that her work and her book have bemused and pleased her relatives, including an aunt who is quite delighted to have an author in the family. “My parents were a bit confused to start,” she said. “But I was a middle child and they let me do my own thing.” Eventually, she said, they realised, “Oh, she’s done all right.”

Flies can be startling in their appearance as well as their behaviour. One Middle Eastern fruit fly has patterns on its wings that look something like spiders. No one knows why. Another fly, Achias rothschildi, must swallow air to inflate its eye stalks when it first emerges as an adult.

There are, McAlister notes in her book, limits to even her affinity for flies. Houseflies, for instance, may be affected by climate change. According to one projection, the population could increase by 244 per cent by 2080.

“That’s a lot of flies,” she writes, “even for my tastes.”

Presumably, many flies will also suffer with climate change. A recent paper looking at all insects reported an apparent decline that may already be linked to global warming.

There are countless mysteries remaining in the fly world – big ones, like how many species of flies there really are, and more limited ones, like the insect with the big orange head, the bone skipper fly. It eats carcasses, but only ones that have been picked over, and comes out at night in the winter. It was thought to be extinct until it was rediscovered a few years ago.

McAlister is doing her part to recruit a new generation to solve these puzzles and others by appealing to the same instincts in young people that led her to seek out the spoils of hunting house cats.

“I was telling these kids about maggots and decomposing and why they’re fun,” she recalled. One of them later persuaded his father to leave a rotten chicken in the yard and to plant an iPhone nearby to make a video as it pulsed with the energy of its consumers.

Helpfully, father and son sent McAlister the video. She looks on the bright side: “Hopefully, by inspiring this little kid to have a rotten chicken in his garden, we can spark their interest.”

On such outreach rests the future of dipterology.

© New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks