Scientists spot huge, ancient collision in space that could change our understanding of the universe

Region is by far the most active place ever observed in the universe

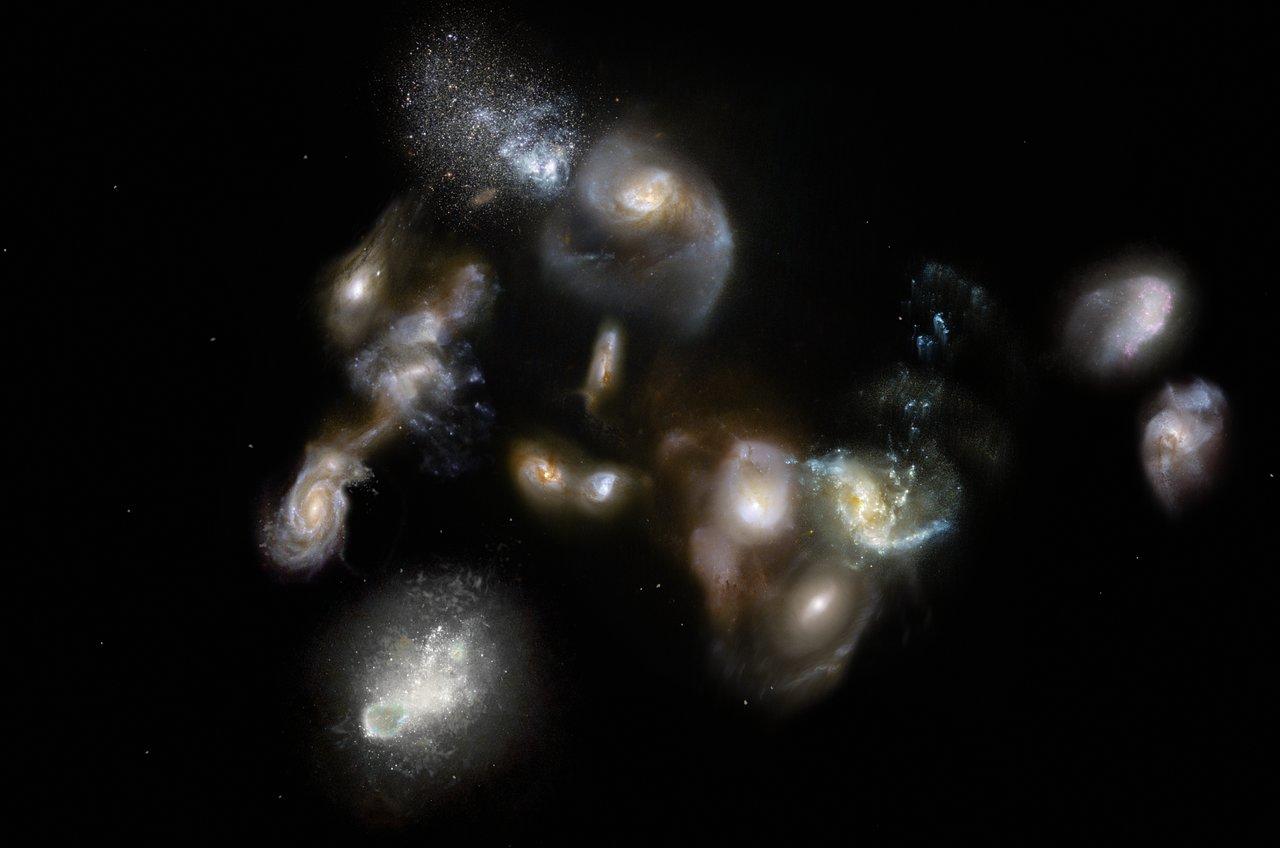

Scientists have spotted a colossal collision of many different galaxies, deep in the universe and in time.

The breakthrough marks the first time that scientists have ever seen such a megamerger. And the discovery could change our understanding of the way the universe works.

The huge collision of 14 different galaxies was seen at least 90 per cent of the way across the universe. At that distance, what we see is the universe at only a tenth of its current age, allowing us to peek back into time into the formation of new galaxies.

As it grows up, the combined superstructure will go onto become one of the biggest things in the entire universe.

"Having caught a massive galaxy cluster in throes of formation is spectacular in and of itself," said Scott Chapman, an astrophysicist at Dalhousie University in Halifax, Canada, who specialises in observational cosmology and studies the origins of structure in the universe and the evolution of galaxies.

"But, the fact that this is happening so early in the history of the universe poses a formidable challenge to our present-day understanding of the way structures form in the universe," he said.

Each of the 14 galaxies are starburst galaxies, throwing out new stars. Together the region is by far the most active place ever seen in the universe, and is producing thousands of new stars every year.

Finding all of those stars is perplexing, because such activity is so energetic that it consumes its gas extraordinarily fast. Scientists are not clear how they have all managed to be in the same place, shining so brightly.

"The lifetime of dusty starbursts is thought to be relatively short, because they consume their gas at an extraordinary rate," said Iván Oteo from the University of Edinburgh, who led one of the two teams that found the huge collision.

"At any time, in any corner of the Universe, these galaxies are usually in the minority. So, finding numerous dusty starbursts shining at the same time like this is very puzzling, and something that we still need to understand."

It's still not clear how they are managing to do that, so quickly and when the galaxy is so young.

"There's some special aspect of this environment that's causing the galaxies to form stars much more rapidly than individual galaxies that aren't in this special place," says Hayward. It is possible that the gravity from the other galaxies is compressing the gas within each of the individual ones, scientists said.

Scientists first spotted the galaxies as faint smudges of light, seen from the South Pole Telescope and the Herschel Space Observatory. Scientists then used an even more powerful telescope known as the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) to peer back into space to explore them in more detail – and found they were coming from the very early universe, only 1.5 billion years after the Big Bang.

They are so far away that we are seeing them at a very early stage of their development. But with time they will go on to become form a huge cluster, of the kind of giant structures we see around the universe.

It is not clear how we managed to spot such a giant collision so early on in the universe.

"How this assembly of galaxies got so big so fast is a bit of a mystery, it wasn't built up gradually over billions of years, as astronomers might expect," said Tim Miller, a doctoral candidate at Yale University and coauthor on the paper.

"This discovery provides an incredible opportunity to study how galaxy clusters and their massive galaxies came together in these extreme environments."

But the researchers can now use detailed computer simulations to understand what will happen in the wake of that collision.

"ALMA gave us, for the first time, a clear starting point to predict the evolution of a galaxy cluster. Over time, the 14 galaxies we observed will stop forming stars and will collide and coalesce into a single gigantic galaxy," said Chapman.

The new research, 'A massive core for a cluster of galaxies at a redshift of 4.3', is published in Nature.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks