Mice playing VR games shed light on how long-term memories are stored in brain

Researchers discovered the brain region linking short-term memory to long-term memory.

Scientists have analysed the brains of mice playing virtual reality (VR) games with the aim to learn more about how long-term memories are stored.

The rodents ran on a rotating styrofoam ball – much like a treadmill – while viewing mazes in VR.

The mice received high rewards – unlimited sugar water – for making certain turns in the maze.

When the turns were different, it resulted in either only a few drops of sugar water or a puff of air to the face.

Josue Regalado, a PhD student at Rockefeller University in the US, said: “We structured the virtual reality tasks so that they required a lot of engagement from the mouse in order to start the trial, run through the mazes and get the rewards.

The key was that the mice could learn all three outcomes in the short-term – very high rewarding, low rewarding, and adverse – but only the high reward would be remembered a month out, because it was the most salient memory

“The more explicit and cognitive the task, the more we’re able to look at how the different brain regions are engaged.”

After the mice learned the three different scenarios, they were assessed again a few weeks later.

The team found the mice were still scampering toward the areas in the maze that had resulted in high rewards.

This was a clear indication that they only remembered decisions that had resulted in big rewards, the team added.

Mr Regalado said: “The key was that the mice could learn all three outcomes in the short-term – very high rewarding, low rewarding, and adverse – but only the high reward would be remembered a month out, because it was the most salient memory.

“That way, we could measure the differences in the neural circuit when recording memories that will be conserved.”

The researchers then monitored the brain activity of the mice while they were performing the tasks.

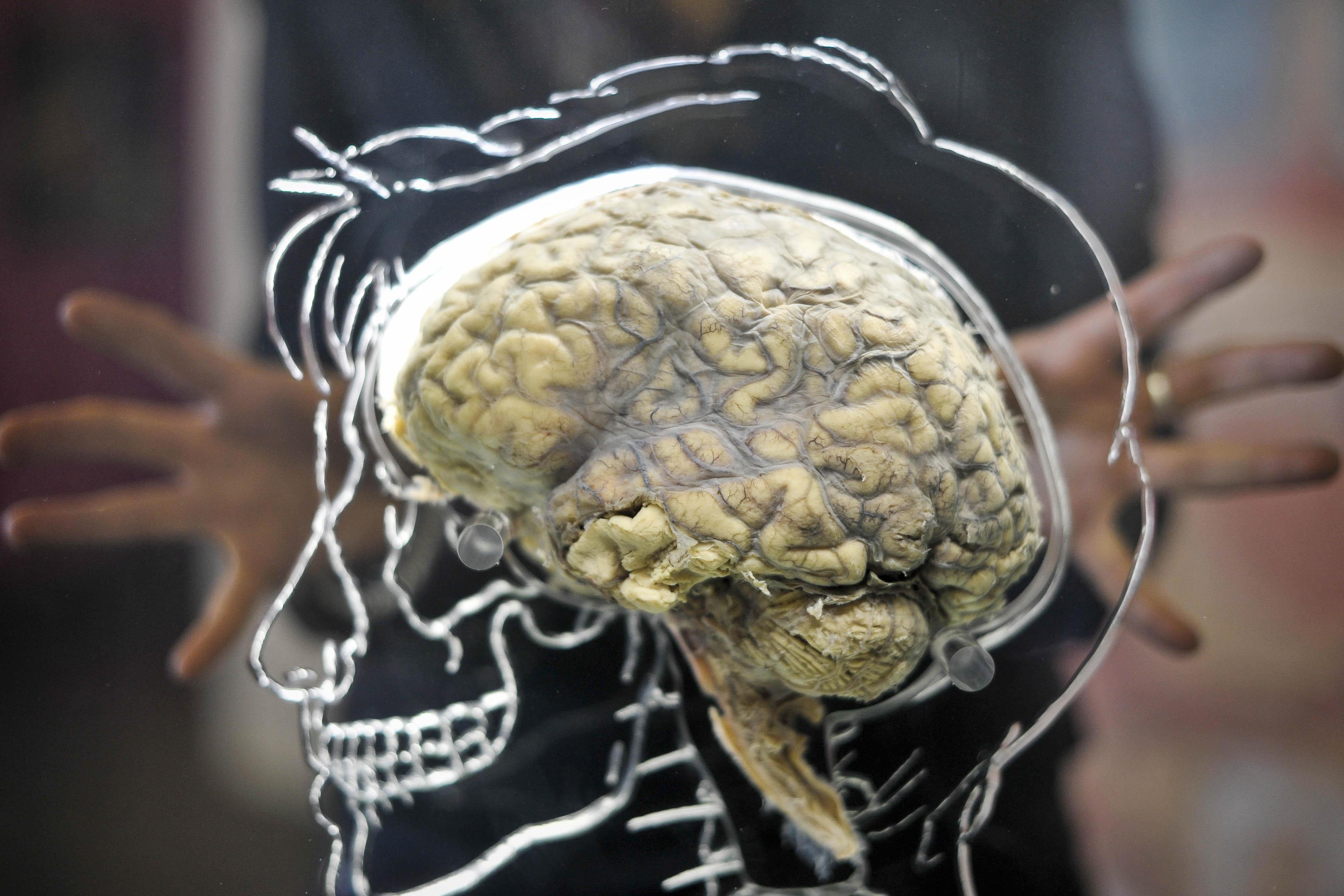

They focused on two areas of the brain – the hippocampus, where short-term memories are stored, and the anterior thalamus, which regulates emotions.

The aim was to find out how short-term memories in the hippocampus became long-term memories stored in the anterior cingulate cortex, which is involved with emotion formation, learning and memory.

Findings indicated the anterior thalamus played a role in consolidating memories deemed rewarding, which were then were passed on to the cortex.

Andrew C Toader, also a PhD student at the Rockefeller University, said: “The analogy would be your birthday dinner versus the dinner you had three Tuesdays ago.

“You’re more likely to remember what you had on your birthday because it’s more rewarding for you — all your friends are there, it’s exciting — versus just a typical dinner, which you might remember the next day but probably not a month later.”

As part of the next steps, the researchers are planning to investigate how the anterior thalamus contributes to long-term memory storage.

Priya Rajasethupathy, a neuroscientist and assistant professor at the Rockefeller University, said: “The question is what the thalamus does when a memory is valuable and needs to be saved long-term, that it doesn’t do for less valuable memories.”

The research is published in the journal Cell.

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks