Intelligent people's brains wired differently to those with fewer intellectual abilities, says study

Scientists claim to have found a correlation between how well wired-up some individuals were to their cognitive abilities and general success in life

The brains of high-achieving individuals are wired up differently to those of people with fewer intellectual or social abilities according to one of the first studies to find a physical link between what goes in the brain and a person’s overall lifestyle.

An analysis of the “connectivity” between different parts of the brain in hundreds of healthy people found a correlation between how well wired-up some individuals were to their cognitive abilities and general success in life, scientists said.

The researchers found that “positive” abilities, such as good vocabulary, memory, life satisfaction, income and years of education, were linked significantly with a greater connectivity between regions of the brain associated with higher cognition.

This was in contrast to the significantly lower brain connectivity of people who scored high in “negative” traits such a drug abuse, anger, rule-breaking and poor sleep quality, the scientists said.

“We’ve tried to see how we can relate what we see in the brain to the behavioural skills we can measure in different people. In doing this, we hope to able to understand what goes on ‘under the bonnet’ of the brain,” said Professor Stephen Smith of Oxford University, who led the study published in Nature Neuroscience.

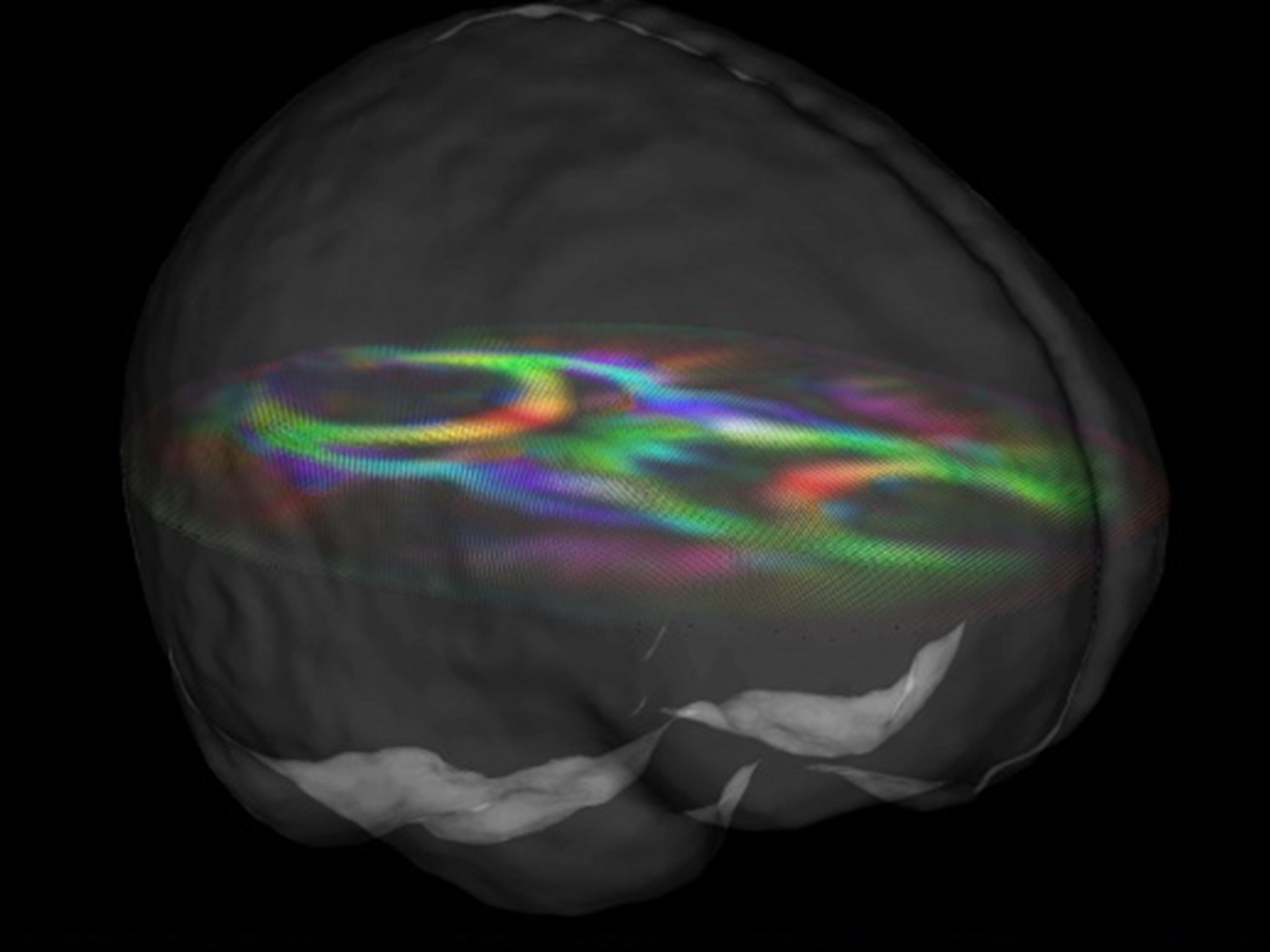

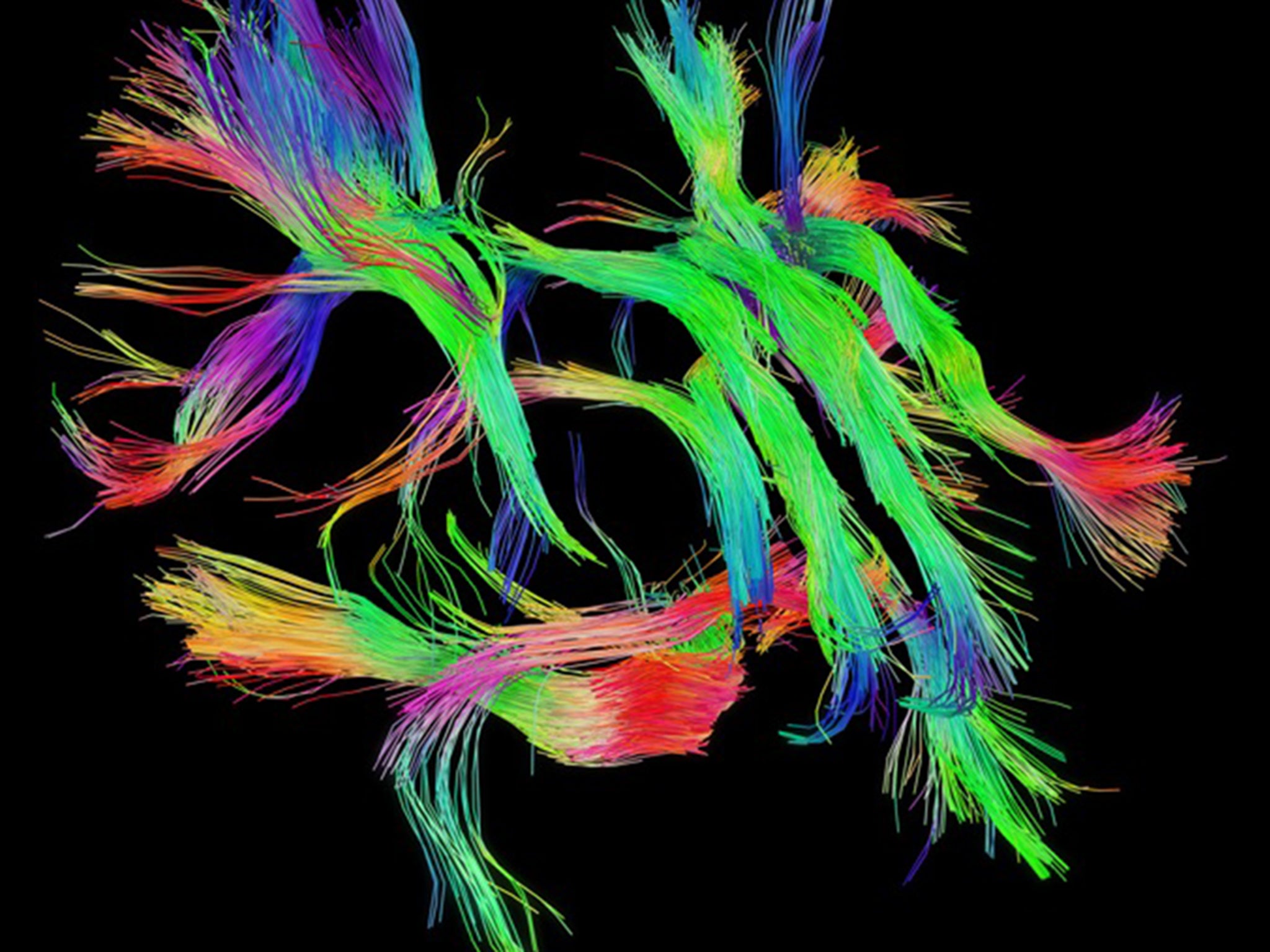

The scientists were part of the $30m (£20m) Human Connectome Project funded by the US National Institutes of Health to study the neural pathways of the brain. Connectomes have been likened to taking real-time images of the living circuit diagrams governing the communication of signals from one part of the brain to another.

They compared the “connectomes” of 461 health people taken by real-time brain scanners called functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and attempted to see if there were any significant correlations with 280 different behavioural or demographic measures, such as language vocabulary, education and even income.

Each fMRI analysis looked at the connectivity – the amount of nerve signalling – that takes place between about 200 different regions of the brain. The one that stood out was the connectivity between the parts of the brain involved in so-called higher-level cognition, such as language and learning, Professor Smith said.

“You can think of it as a population-average map of 200 regions across the brain that are functionally distinct from one another. Then we looked at how much all of those regions communicated with each other, in every participant,” Professor Smith said.

“The quality of the imaging data is really unprecedented. Not only is the number of subjects we get to study large, but the resolution of the fMRI data is way ahead of previous large datasets,” he said.

The ability to measure the amount of nerve signalling between different parts of the brain, especially those involved in high cognition such as learning and memory, could help scientists to better understand the nature of general intelligence, which is currently measured by tests that examine a range of intellectual skills.

“It may be that with hundreds of different brain circuits, the tests that are used to measure cognitive ability actually make use of different sets of overlapping circuits,” Professor Smith said.

“We hope that by looking at brain-imaging data we’ll be able to relate connections in the brain to the specific measures, and work out what these kinds of test actually require the brain to do,” he said.

It may also be possible to use the research to work out how to train people to improve their brain connectivity and therefore push than up the scale so that they achieve more than they otherwise would, he added.

“It’s a question of whether it’s possible to move people up the axis of connectivity. We know from other research that it is possible to improve cognitive performance with training, but what we don’t know yet is whether this is true of connectivity,” he explained.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks