Scientists complete first map of an insect brain

Achievement brings experts closer to true understanding of the mechanism of thought, researchers say

Researchers have built the first-ever map of an insect’s brain, according to a new study.

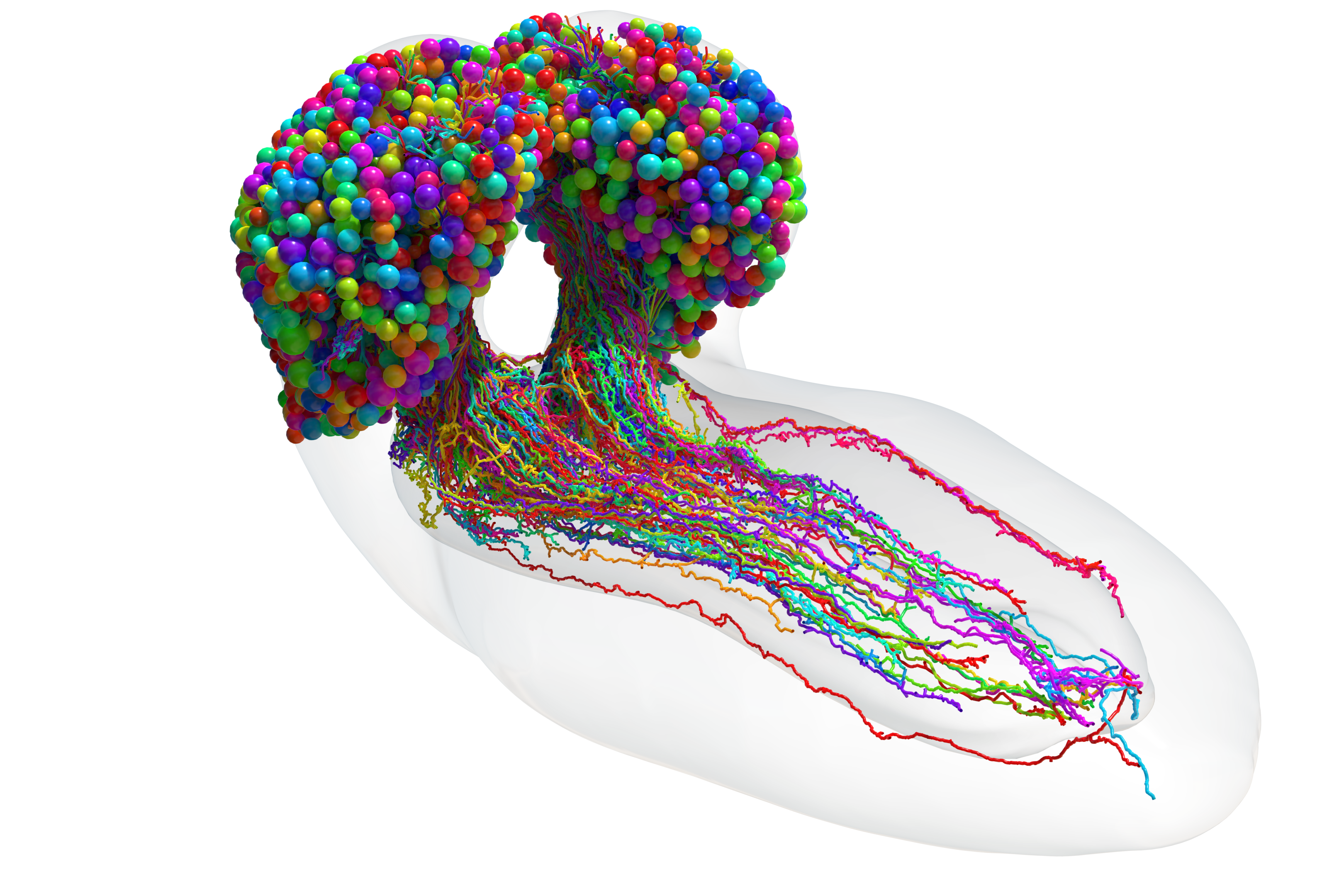

The map shows every single neuron (messenger cell) in the brain of a baby fruit fly, and how they are wired together.

Scientists say the landmark achievement in neuroscience brings experts closer to a true understanding of the mechanism of thought.

The map of the 3,016 neurons that make up the larva’s brain and the detailed circuitry of neural pathways within it is known as a connectome.

This is a big step forward in addressing key questions about how the brain works

It is the largest complete brain connectome described yet, researchers say.

Professor Marta Zlatic and Professor Albert Cardona, of the Medical Research Council Laboratory of Molecular Biology based at the University of Cambridge, along with colleagues from the University of Cambridge and Johns Hopkins University and others led the research.

An organism’s nervous system, including the brain, is made up of neurons which are connected to each other via synapses.

In the form of chemicals, information passes from one neuron to another through these contact points.

Prof Zlatic said: “The way the brain circuit is structured influences the computations the brain can do.

“But, up until this point, we’ve not seen the structure of any brain except of the roundworm C. elegans, the tadpole of a low chordate, and the larva of a marine annelid, all of which have several hundred neurons.

“This means neuroscience has been mostly operating without circuit maps.

“Without knowing the structure of a brain, we’re guessing on the way computations are implemented.

“But now, we can start gaining a mechanistic understanding of how the brain works.”

Jo Latimer, head of neurosciences and mental health at the Medical Research Council, said: “This is an exciting and significant body of work by colleagues at the MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology and others.

“Not only have they mapped every single neuron in the insect’s brain, but they’ve also worked out how each neuron is connected.

This detailed understanding may lead to therapeutic interventions in the future

“This is a big step forward in addressing key questions about how the brain works, particularly how signals move through the neurons and synapses leading to behaviour, and this detailed understanding may lead to therapeutic interventions in the future.”

Current technology is not advanced enough to map the connectome for higher animals such as large mammals.

But Prof Zlatic added: “All brains are similar – they are all networks of interconnected neurons – and all brains of all species have to perform many complex behaviours: they all need to process sensory information, learn, select actions, navigate their environments, choose food, recognise their conspecifics, escape from predators etc.

“In the same way that genes are conserved across the animal kingdom, I think that the basic circuit motifs that implement these fundamental behaviours will also be conserved.”

In order to build a picture of the fruit fly larva connectome, researchers scanned thousands of slices of the larva’s brain.

They reconstructed the resulting images into a map of the fly’s brain and painstakingly annotated the connections between neurons.

As well as mapping the 3,016 neurons, they mapped an incredible 548,000 synapses.

The work took researchers 12 years to complete, with the imaging alone taking about a day per neuron.

The findings are published in the Science journal.

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks