Bizarre tusked creature that lived in Antarctica 250 million years ago ‘survived by hibernating’

History of hibernation could be much longer than previously estimated, new fossil study suggests

Paleontologists have discovered evidence of hibernation in a bizarre species of tusked animal which lived 250 million years ago in what is now Antarctica.

Winter hibernation is a familiar trait among animals on the planet today, particularly those which live close to or within polar regions. It allows such species to survive through months when food is scarce, temperatures drop and daylight hours are short.

The new research indicates this adaptation may have a longer history than previously thought.

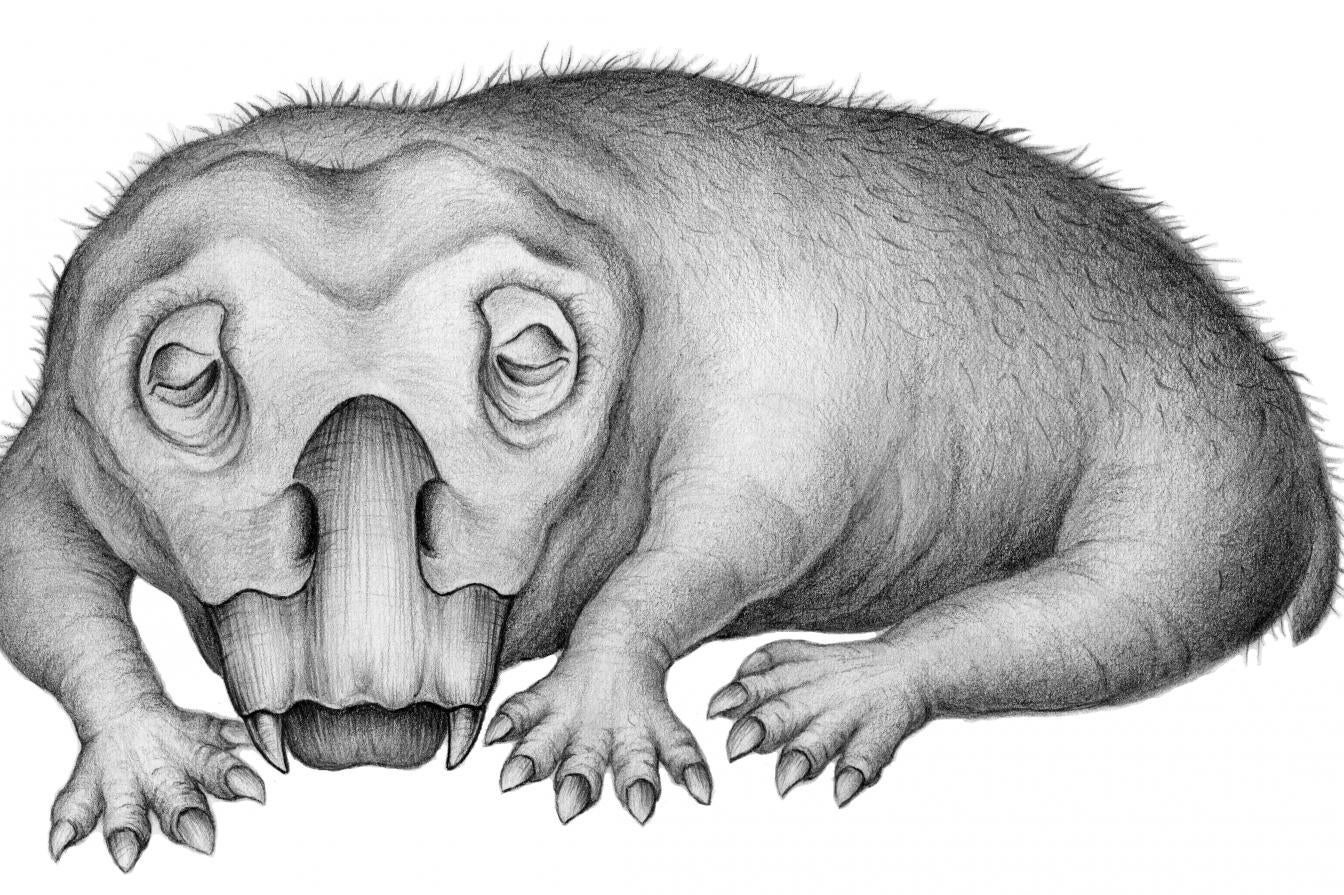

Lystrosaurus - a heavily built pig-sized herbivorous animal with tusks and a beak - lived on many continents and was one of few species which survived the extinction event which killed the dinosaurs.

But it is the remains of lystrosaurus populations found on Antarctica which have revealed the animal’s predilection for hibernation.

The scientists compared the fossilised tusks from Antarctica with those found in South Africa.

They found that the tusks from the two regions showed similar growth patterns, with layers of dentine deposited in concentric circles like tree rings. But the Antarctic fossils also had an additional feature which was rare or absent in tusks collected further north: closely-spaced, thick rings, which likely indicate periods of less deposition due to prolonged stress, according to the researchers.

“The closest analog we can find to the 'stress marks' that we observed in Antarctic lystrosaurus tusks are stress marks in teeth associated with hibernation in certain modern animals,” said lead author Megan Whitney, a postdoctoral researcher at Harvard University.

“Animals that live at or near the poles have always had to cope with the more extreme environments present there.

“These preliminary findings indicate that entering into a hibernation-like state is not a relatively new type of adaptation. It is an ancient one.”

Though present-day South Africa and the Antarctic region where the fossils found were not in the same place 250 million years ago, the collection sites in Antarctica were at about 72 degrees south latitude - still well within the Antarctic Circle, at 66.3 degrees south. The collection sites in South Africa were more than 550 miles north during the Triassic at 58 to 61 degrees south latitude, far outside the Antarctic Circle.

The research team said they cannot definitively conclude that lystrosaurus underwent true hibernation - which is a specific, weeks-long reduction in metabolism, body temperature and activity.

They said the stress marks could have been caused by another hibernation-like form of torpor, such as a more short-term reduction in metabolism.

“To see the specific signs of stress and strain brought on by hibernation, you need to look at something that can fossilise and was growing continuously during the animal's life,” said co-author Christian Sidor, a University of Washington professor of biology and curator of vertebrate paleontology at the Burke Museum.

“Many animals don't have that, but luckily lystrosaurus did.”

Due to the rarity of the fossils the researchers have not been able to examine large numbers of lystrosaurus tusks. In total they studied cross-sections of tusks from six Antarctic lystrosaurus and four lystrosaurus from South Africa.

But if analysis of additional Antarctic and South African lystrosaurus fossils confirms their discovery, it could also point to a specific trait seen in these ancient animals which is still observed in modern mammals.

“Cold-blooded animals often shut down their metabolism entirely during a tough season, but many endothermic or ‘warm-blooded’ animals that hibernate frequently reactivate their metabolism during the hibernation period,“ said Dr Whitney.

“What we observed in the Antarctic lystrosaurus tusks fits a pattern of small metabolic reactivation events during a period of stress, which is most similar to what we see in warm-blooded hibernators today.”

The research is published in the journal Communications Biology.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks