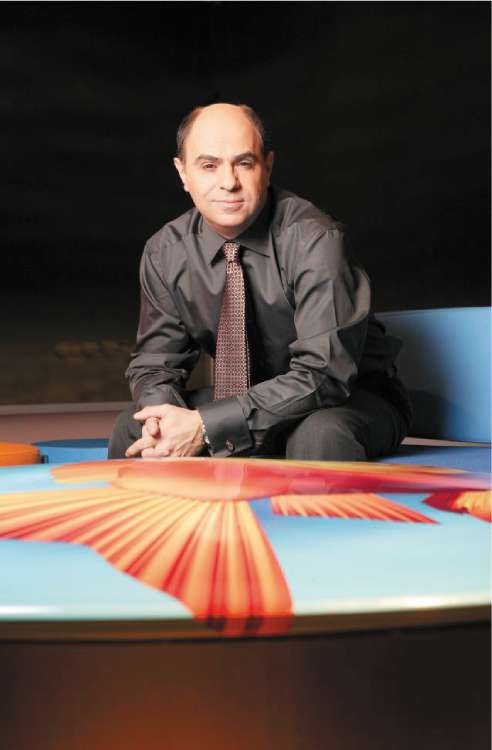

Adam Shaw: A good face for radio ... and not bad at it either

As a trained Shakespearean actor, Adam Shaw knows audiences love the 'power, greed and vanity of a good business story. Amol Rajan meets Today's new recruit

Maybe it's his bald pate, or his mildly rotund jaw, or the arched eyebrows that give him more than a passing resemblance to David Suchet, of Agatha Christie's Poirot fame. Either way, Adam Shaw has definitely got a great face for television. Not in the conventional way of a Kaplinsky or a Buerk, perhaps, but in the sort of understated theatricality one might more readily associate with Elizabethan tragedy.

Which is not surprising, given his years spent touring the country with fringe theatres and even spending a season at the Royal Shakespeare Company. "Acting, and specifically the process of auditioning, taught me an enormous amount about myself not least that I wasn't cut out for the stage," Shaw says. "It's not true that I stumbled into journalism after failing in my first career choice; I prefer to think of it as a kind of natural progression".

Shaw, who has co-presented Working Lunch on BBC2 for 13 years, has received a further compliment from senior executives at the BBC. They think he's got a great face for radio, too, and have granted him the prestigious duty of replacing Greg Wood in the business slot of Radio 4's flagship Today programme. He starts there tomorrow.

Coming not long after he filled the enormous gap left by Adrian Chiles the faux-gruff Brummie whose departure from the lead role in Working Lunch precipitated his becoming one of Britain's most sought-after television personalities the additional role suggests that these are purple times for Shaw.

"I'm not thinking about it like that," he says. "I see it as part of a much wider trend. In our current economic climate the importance of business journalism is greater than ever. People are feeling the pinch in a way they haven't for a long time, and it's up to journalists who talk to businesses to work harder than ever".

In particular, Shaw says, journalists who know what a tough economic climate can do to people's living standards. "I'm not going to pretend I'm poor," says Shaw, who was educated at an inner-city comprehensive in Kilburn, north-west London, "because I'm not. But I do know empathy is a big part of what I do, and my childhood certainly gives me a sense of perspective".

In one respect he is undoubtedly right: business journalism is thriving in Britain. Evan Davis, the BBC's former Economics Editor, recently moved into Carolyn Quinn's presenter's chair at Today. The Financial Times won newspaper of the year at the British Press Awards on 8 April, largely in recognition of its coverage of Northern Rock and the worldwide credit crunch. Robert Peston, the BBC's mercurial business editor and a veteran of several newspapers, has won various awards for his agenda-setting coverage of the same issues.

Meanwhile, James Harding and Will Lewis, the relatively new editors of both The Times and The Daily Telegraph, were promoted from the jobs of business editor and city editor respectively. Why the flurry of success?

"Businesses themselves are only just learning to talk to the media," Shaw says. "For a very long time many of them were awful at their own public relations, but now many of them are realising how essential good journalism is to their own work. In such an environment, people like me, who spend hours poring over obscure spreadsheets or being titillated by quarterly profit margins, find ourselves becoming indispensable to a lot of very powerful people. And that, ultimately, is why business and a corporate culture more widely is thriving: many people are finally getting the message that business is about emotions and turbulence, about power, greed, vanity, avarice things that people want to know about."

His theatrical leanings never less than tangible, Shaw's enthusiasm is infectious. It rises to a kind of peak as he describes the moral imperative behind his work by invoking the ubiquitous mantra of "relevance".

"Essentially, I think of what I do as running a translation service," he says. "There's no question that the whole language of business in the media was for a long time a deliberate and organised attempt at obfuscation. At times, this is malicious; at other times it's simply the by-product of the jargon pervading all business life".

The spectre of George Orwell's celebrated disdain for political language "designed", Orwell said, "to make lies sound truthful and murder respectable, and to give an appearance of solidity to pure wind" looms over Shaw's words. "Business language is frequently devoted to making the highly relevant seem irrelevant, and to disguising failure as success," says Shaw. "I'll never flinch from asking the simple questions."

If this is true, what are we to make of the swelling success of programmes such as The Apprentice and Dragons' Den, which take a business ethic as their foundation? Are they really just vehicles for meretricious rich people?

"There is much to admire about those programmes but I think we should stop short of seeing them as some sort of perfect business model. Both those productions are highly stylised, and I'm not sure I'd want to work for any of the people on them".

Despite studying Economics at the University of Kent at Canterbury, Shaw's route to Working Lunch was far from conventional. Aside from an "unexceptional" season at the RSC, he spent years "touring theatres in the West Midlands living in awful digs", and even spent some time doing bit-parts in Soho. "It was mostly Kafka, a bit of Bulgakov; esoteric stuff."

After getting a job at the BBC as a junior producer he worked on The Late Show and Watchdog, then moved to BSB (which later merged with Sky) to work in its business unit. He only moved in front of the camera when, after several other presenters retired, the finger landed on him as "last man standing".

Now, after more than a decade presenting Working Lunch, which has a solid, loyal audience of half-a-million viewers, Shaw is both a well-known face and a trusted brand. What with his new slot on Today adding to his profile, is he in danger of becoming a something of a celebrity?

"I'm not sure that's very likely," he says. "I'm far more worried about when I'm going to sleep." Shaw, who spends his afternoons in the City meeting contacts and getting stories, will have to wake at 3.30am for Today, carry on presenting Working Lunch through the afternoon, and then get out and about among the power-hungry in the afternoon. "It's proper journalism," he says, unperturbed. "I still believe in it."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks