A guide to time capsules: 1915 and all that

An excavation of the New York Times' archive has revealed the existence of a time capsule due to be dug up next year in the presence of Obama. What could be in it, asks Simon Usborne

Page 26 of The New York Times for Sunday, 28 July 1917 is a busy place. According to the style of the time, dozens of stories compete for attention. "Eskimo" from Greenland becomes US citizen. Church treasurer accused of embezzlement. City glass merchant dies of pneumonia. But one article leaps forward thanks to the date in its headline: "To open copper box in 2015: Unborn officials and others are invited to ceremony."

The story itself, unearthed from the newspaper's archive this week and now circulating online, begins: "The unborn editors of The New York Times of 2015 have been invited to attend, on the second Saturday of September of that year, the opening of the Louis H Eisenlohr box at Ashburnham, Mass, which was placed in the vault of the town treasurer in 1915 with instructions that it not be opened for 100 years."

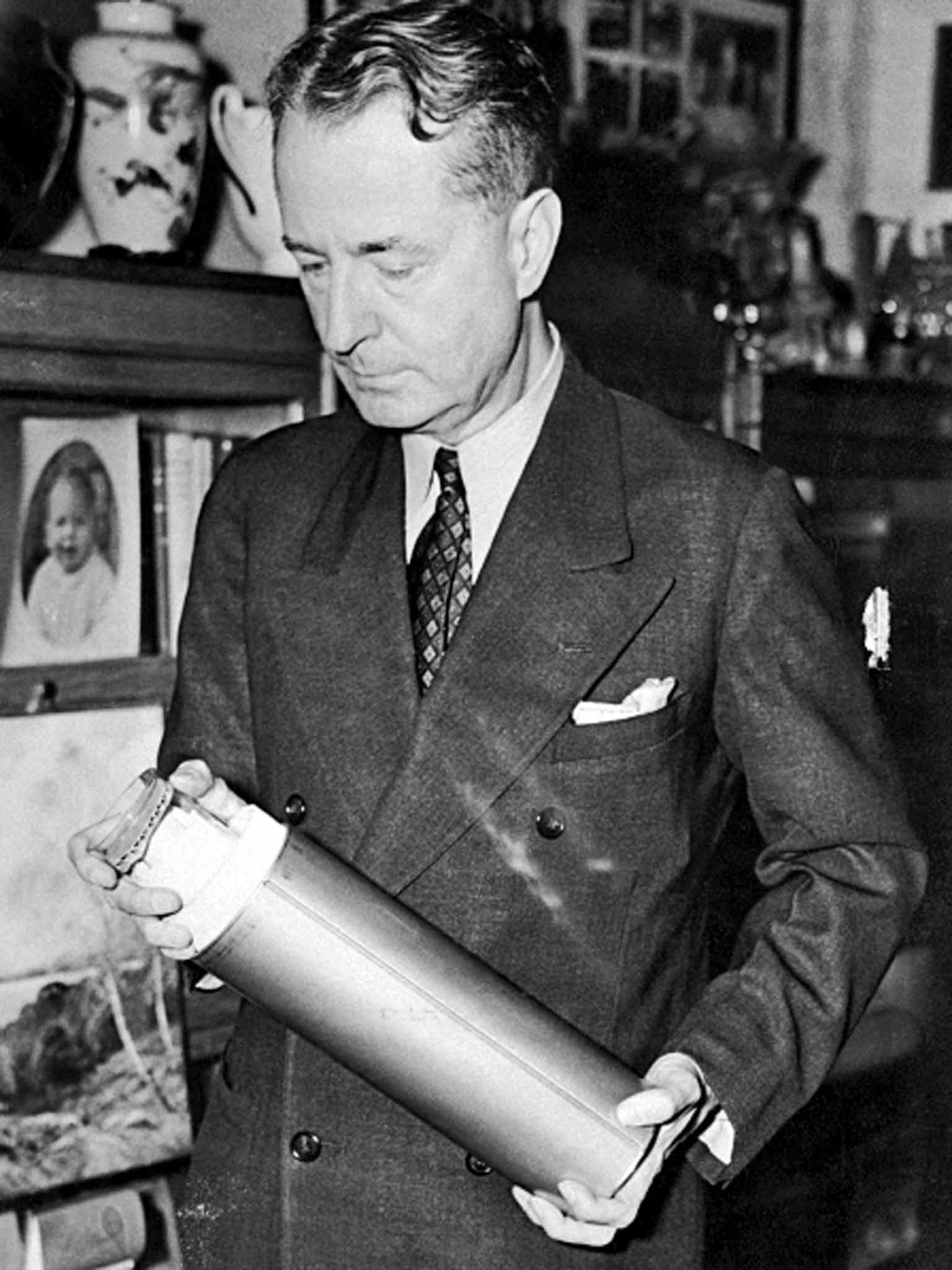

The box is a time capsule, one of countless such caches sharing soil space all over the world. According to the 1917 article, the box in Ashburnham, a town 60 miles west of Boston, contains "messages from prominent men and records of 1915, including a copy of the Times, and other matter of probable interest to those alive in 2015." Intriguing stuff, apparently brought to light yesterday by Masuma Ahuja, a digital editor at The Washington Post. She tweeted the story with the very contemporary exclamation: "Woah".

Further excavation of the Times archives brings up an earlier, 1916 story about the capsule. It carries more detail, including the existence of a second box under an elm tree at Cushing Academy, a school in Ashburnham. It, too, was buried by Mr Eisenlohr, a wealthy Texan industrialist. There is also information about a fund set up that would be worth $5,000 by next year, enough to finance an "appropriate" opening ceremony, to which the US President, among others, should be invited.

Obama's schedule, should he still be the boss, may or may not include a diversion to Ashburnham, where the boxes may turn out to be pretty dull. An administrator for the town said it was aware of its capsule, but did not have details to hand. Bad news from Cushing Academy, meanwhile. A librarian there tells me that its capsule was unearthed by construction workers in the 1980s and was "sadly found to have corroded so badly that the capsule and its contents had been destroyed by the elements".

The Times did not respond to enquiries, but its interest 100 years ago and this week's stories online reflect our enduring obsession with hiding stuff for posterity. At Oglethorpe University in Atlanta, the International Time Capsule Society documents all known capsules, and estimates that there are more than 10,000 of varying size and interest. The university is also the site of the Crypt of Civilisation, a swimming pool-sized chamber sealed in 1940 that contains more than 640,000 pages of micro-filmed material, as well as newsreels, recordings and "a device designed to teach the English language to the crypt's finders". The president of the university at the time decreed that the vault must not be opened until 28 May 8113, more than 6,000 years from now.

The French Keo project, meanwhile, delayed until at least next year, will involve the launch into space of a capsule containing messages as well as a drop of human blood, samples of seawater and the DNA of the human genome. It will not return to Earth for 50,000 years.

Sometimes, we are not made to wait so long. Andy Warhol turned time capsules into art in the years before his death in 1987, by packing his possessions and studio ephemera into 612 cardboard boxes that he called time capsules. The last-but-one of these boxes was opened this month before a paying audience at an event in the artist's native Pittsburgh. The collection has so far revealed thousands of items including gallery flyers, fan letters and Campbell's soup tins, as well as, less appetisingly, toenail clippings and used condoms.

British time capsules are fewer and tend to be less ambitious or imaginative. In 2000, Blue Peter dug up a capsule it had buried in its garden in 1971, containing the first decimal coins and a photo of Valerie Singleton. Two years earlier, the BBC show buried a separate capsule under the foundations of the Millennium Dome. It is due to be opened in 2050 and contains (spoiler alert) an insulin pen, a France '98 football and a set of Teletubby dolls.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks