The 20 technologies that defined the first 20 years of the 21st Century

The apps, gadgets and breakthroughs that shaped the last two decades

The early 2000s were not a good time for technology. After entering the new millennium amid the impotent panic of the Y2K bug, it wasn’t long before the Dotcom Bubble was bursting all the hopes of a new internet-based era.

Fortunately the recovery was swift and within a few years brand new technologies were emerging that would transform culture, politics and the economy.

They have brought with them new ways of connecting, consuming and getting around, while also raising fresh Doomsday concerns. As we enter a new decade of the 21st Century, we’ve rounded up the best and worst of the technologies that have taken us here, while offering some clue of where we might be going.

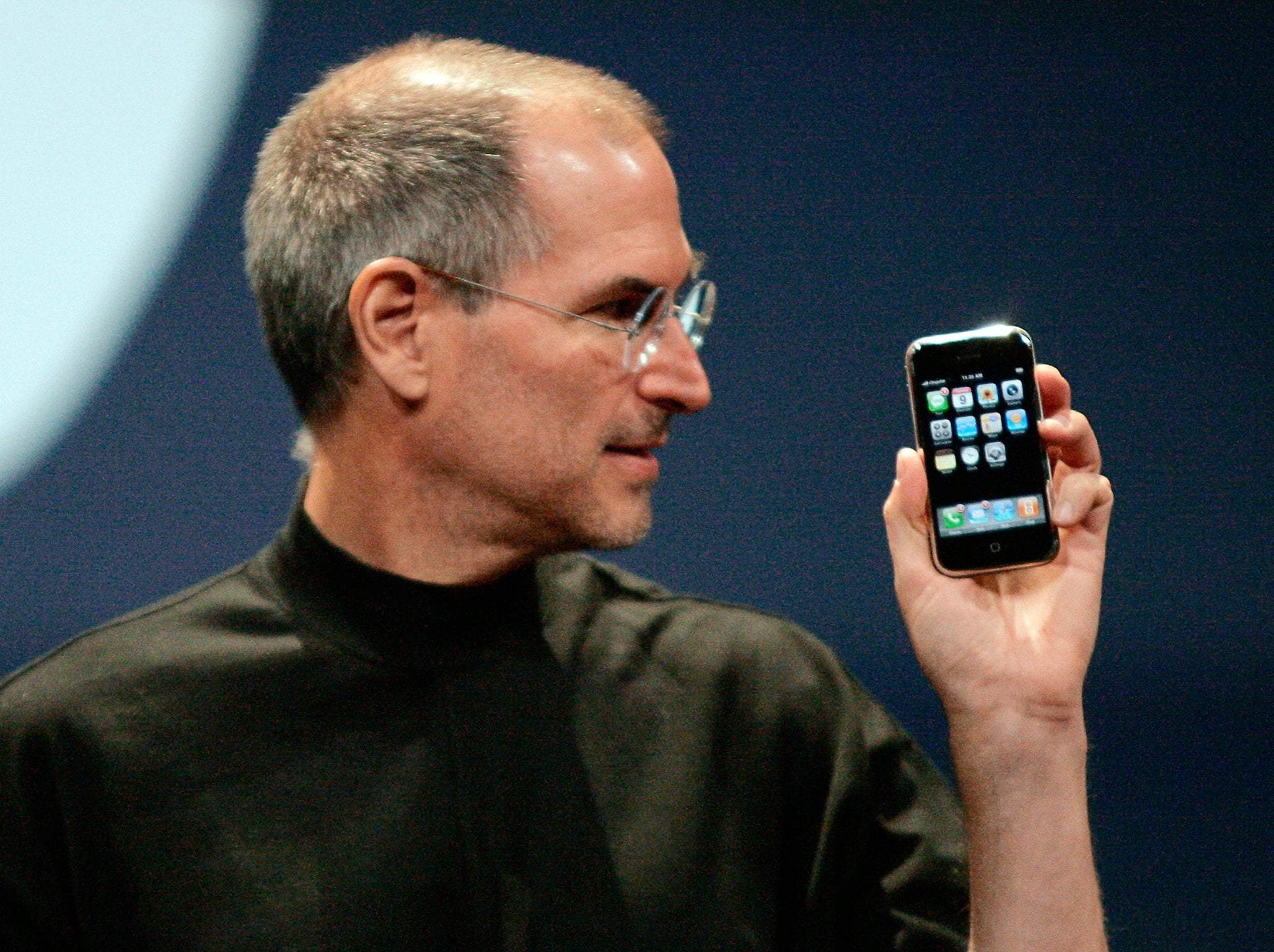

iPhone

There was nothing much really new about the iPhone: there had been phones before, there had been computers before, there had been phones combined into computers before. There was also a lot that wasn’t good about it: it was slow, its internet connection barely functioned, and it would be two years before it could even take a video.

But as the foremost smartphone it heralded a revolution in the way people communicate, listen, watch and create. There has been no aspect of life that hasn’t been changed by the technologies bundled up in the iPhone – an ever-present and always-on internet connection, a camera that never leaves your side, a computer with mighty processing power that can be plucked out of your pocket.

The 2000s have, so far, been the era of mobile computers and social networking changing the shape of our cultural, political and social climate. All of those huge changes, for better or worse, are bound up in that tiny phone.AG

Social media

Though few people noticed, online social networks actually began at the end of the last century. The first was Six Degrees in 1997, which was named after the theory that everyone on the planet is separated by only six other people. It included features that became popular with subsequent iterations of the form, including profiles and friend lists, but it never really took off.

It wasn’t until Friend’s Reunited and MySpace in the early 2000s that social networks achieved mainstream success, though even these seem insignificant when compared to Facebook.

Not only did Mark Zuckerberg’s creation muscle its way to a monopoly in terms of social networks, it also swallowed up any nascent competitors in a space that came to be known as social media. First there was Instagram in 2012, for a modest $1 billion, and then came WhatsApp in 2014 for $19bn.

Between all of its apps, Facebook now reaches more than 2 billion people every day. It has come to define the way we communicate and heralded a new era of hyper-connectedness, while also profoundly shaping the internet as we know it. In doing so, Facebook has not only consigned the site Six Degrees to the history books, it has also re-written the theory itself – cutting it down to just three-and-a-half degrees of separation. AC

Bitcoin and cryptocurrency

At the start of this century, the complete reinvention of the entire economic system wasn’t something many people were talking about. But then the 2007-08 financial crisis happened. As mortgages defaulted, companies collapsed, and governments bailed out the banks to the tune of trillions of dollars, people began to wonder if there might be a better way.

One person – or group – believed they had the answer. Satoshi Nakamoto’s true identity may still be a mystery, but their creation of a new “electronic cash system” called bitcoin in 2009 could have implications far beyond just currency. The underlying blockchain technology – an immutable and unhackable online ledger – could potentially transform everything from healthcare to real estate.

Bitcoin is yet to take off as a mainstream form of payment or transform the global economy like it might have promised, but we are barely a decade into the great cryptocurrency experiment. It has inspired thousands of imitators, including those currently being developed by Facebook and China, and it may be another 10 years before its true potential is finally realised. AC

Youtube

“Alright, so here we are, in front of the, er, elephants. And the cool thing about these guys is that they have really, really, really long trunks. And that’s cool.”

It may have been an inauspicious start, but these words would go on to fundamentally transform the way people consume media in the 21st century. It was 23 April, 2005, and Jawed Karim had just uploaded the first ever video to YouTube – a video-sharing website he had helped create.

Just over a year later, Google bought the site for $1.65 billion and the fortunes of Karim, his co-founders, and countless future content creators were changed forever.

There are now hundreds of hours of video published to YouTube every minute – and it all started with that 18-second clip at the zoo. AC

3G, 4G and 5G

Arthur C Clarke famously quipped that “any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic”. But there is surely nothing more like magic – and no magic more powerful – than the fact that the 21st century has brought the ability to instantly connect to information and people at the other side of the world.

First, at the beginning of the century, came 3G, and then 10 years or so later came 4G. Every decade of this century has been marked by new advances in the speed and reliability of mobile data connections.

And those mobile data connections have helped re-write the world that relies on them. Just about every other major breakthrough in technology that came through the 2000s – social media, instant photo sharing, citizen journalism and everything else – relied on having data connections everywhere.

5G – which has ostensibly already rolled out, but is yet to make its full impact – is likely to be similarly transformative through the decade to come, if its evangelists are to be believed.

Debates have raged about whether this constant connectivity – and the distractions and dangers it has brought – has really driven us apart. But that too is surely testament to its power. AG

Gig economy

Many of technology’s biggest developments in the 2000s haven’t really been about technology at all: piracy and then streaming changed how we make and consume culture entirely, social media has turned politics on his head. Nowhere is that more clear than in the gig economy and the apps and websites like Uber, Deliveroo and Airbnb that power it, which claim to be tech businesses but are really new ways of buying and selling labour.

The real revolution of the gig economy was not the technology that powers these apps: there is little difference between calling for a cab and summoning an Uber, really. Nor was it what the companies like to suggest, that they have opened up a new and inspiring way of working that allows anyone to clock on whenever they log on.

Instead, it was the beginning of a process of changing the way that people work and relate to those who fulfil services for them. It is likely that we have not seen the end of the kinds of profound changes that these companies have made to working conditions – or the ways that those workers have fought back. AG

VR and AR

Virtual reality has been the future before: ever since the first stereoscopes, people have been excited about the possibility of disappearing into other worlds that appear before their eyes. But it has never quite arrived.

But in the more recent years of the 2000s it started to look a bit more meaningful. Virtual reality headsets have been pushed out by many of the world’s biggest companies, and consumer computers are finally powerful enough to generate believable worlds that people are happy to spend their time in.

In recent years, much of the focus has turned to augmented reality rather than virtual reality. That technology allows information to be overlaid on top of the real world, rather than putting people into an entirely virtual world. If it comes off – if it is not confined to failed experiments like Google Glass – then it could change the way we interact with the world, potentially giving us information all of the time and could even do away with things like smartphones as our primary way of connecting with technology. AG

Quantum computing

Quantum computing has not really happened yet. A few months ago, researchers announced that they had achieved “quantum supremacy” by doing an operation that would not be possible on a traditional computer – but it was a largely useless, very specific, operation, which didn’t really change anything in itself.

Already, however, the promise – and the threat – of quantum computing is changing the world. It looks set to upend all of our assumptions about computers, allowing them to be unimaginably fast and do work never thought possible. It could unlock new kinds of health research and scientific understanding; it could also literally unlock encryption, which currently relies on impossible calculations that could quickly become very possible with quantum computers.

It isn’t clear when it will arrive, of course; like other potentially revolutionary technologies, it could take a very long time or never arrive at all. But it is sitting there in the future, ready to turn everything on its head – and, as researchers rush to understand it, it is already changing the world. AG

Smart home and voice assistants

No vision of the future would be complete without the ability to speak to and control your home. And now it seems like we are finally living in it.

Through the 2000s, just about everything came to be hooked up to the internet: you could buy smart kettles, internet-enabled doorbells, and a video camera for every room in your house. And to control them came microphones and speakers that you put in your house and could talk to.

But as the smart home and the voice assistants that power it have soared in popularity, they have been beset by concerns, too. Is giving over control of your home to internet-enabled devices safe, when those devices can break down or be seized by hackers? Should we be allowing internet giants like Amazon and Google to put microphones in our home? As we enter the new decade, it looks like our homes are set to be defined not by the capabilities the technology in our homes give us – but who we want to have power over them. AG

Streaming and piracy

Before there was Spotify, there was Napster, and before people were watching movies on Netflix, they were downloading them through PirateBay. Piracy has been one step ahead of legal ways to consume media but in doing so it has led the way for new platforms that now dominate our online lives.

Streaming has not only changed the way we listen to music and watch films, it has also given rise to new ways to create content. Live streaming video games on Twitch is one of the fastest growing mediums, while live video broadcasts through Facebook, Twitter and YouTube give people instant access to everything from street protests to rocket launches.

But as online streaming grows, so does piracy. The ‘world’s biggest online piracy operation’ is currently underway in Saudi Arabia, while PirateBay has just launched a streaming platform that offers more content than Amazon Prime, Netflix and Disney+ combined.AC

Online gaming

It is almost unbelievable to think that playing games against friends once meant crowding around a console in a bedroom. Now, games that even offer the ability to do so are few and far between – and those that are not always connected to the internet and putting you up against strangers are very unusual indeed.

The internet has changed games in other ways, too. One of the most popular forms of entertainment in the world is now live streaming, where people watch other people play games.

Developers can also give people continual updates and extra content through downloadable content, and ask players to repeatedly pay for upgrades through microtransactions. Those changes have made a game not a stable, definitive thing, but a world that is continually developing (and generating more money). AG

Reusable, commercial rockets

Space is hard, famously; more importantly, it is very expensive. Reusable, commercially made rockets could change both.

Over the 2000s, responsibility for much of the technology used to get astronauts into space was handed more and more to private companies such as SpaceX. In order to keep costs down – and their profits up – those companies are working towards making rockets that can be re-used, just like planes, shuttling people up into the sky before dropping back down for the next mission.

SpaceX in particular has made huge strides in this respect, fulfilling a spectacular mission to have its rockets land back down on a barge floating in the sea. But the breakthroughs have not been without their problems. The involvement of commercial companies has come with its critics, who argue that it could compromise safety and make private companies yet more powerful. AG

Driverless and electric cars

It took nearly 50 years for the automobile to dislodge the horse and cart as the main form of transport, but the next great transition in road transport may be just years away thanks to the advent of two new vehicular revolutions in the early 21st century: electric-powered cars and self-driving technology.

Electric cars are already quicker, safer, and more interesting to look at than traditional gas guzzlers, but they still can’t compete in one key area: charge time. Recent battery breakthroughs mean this could soon change, with engineers figuring out a way to recharge an electric car in just 10 minutes – at least in the lab.

Advancements in self-driving cars have been even more drastic. Pioneered by the likes of Tesla’s Autopilot mode, drivers are now able to travel from one place to another almost autonomously. Major automakers like Volvo have even started producing concept vehicles that don’t even include a steering wheel in their design.

Such progress makes it inevitable that at some point in the not-so-distant future, self-driving electric cars will simply be called cars. AC

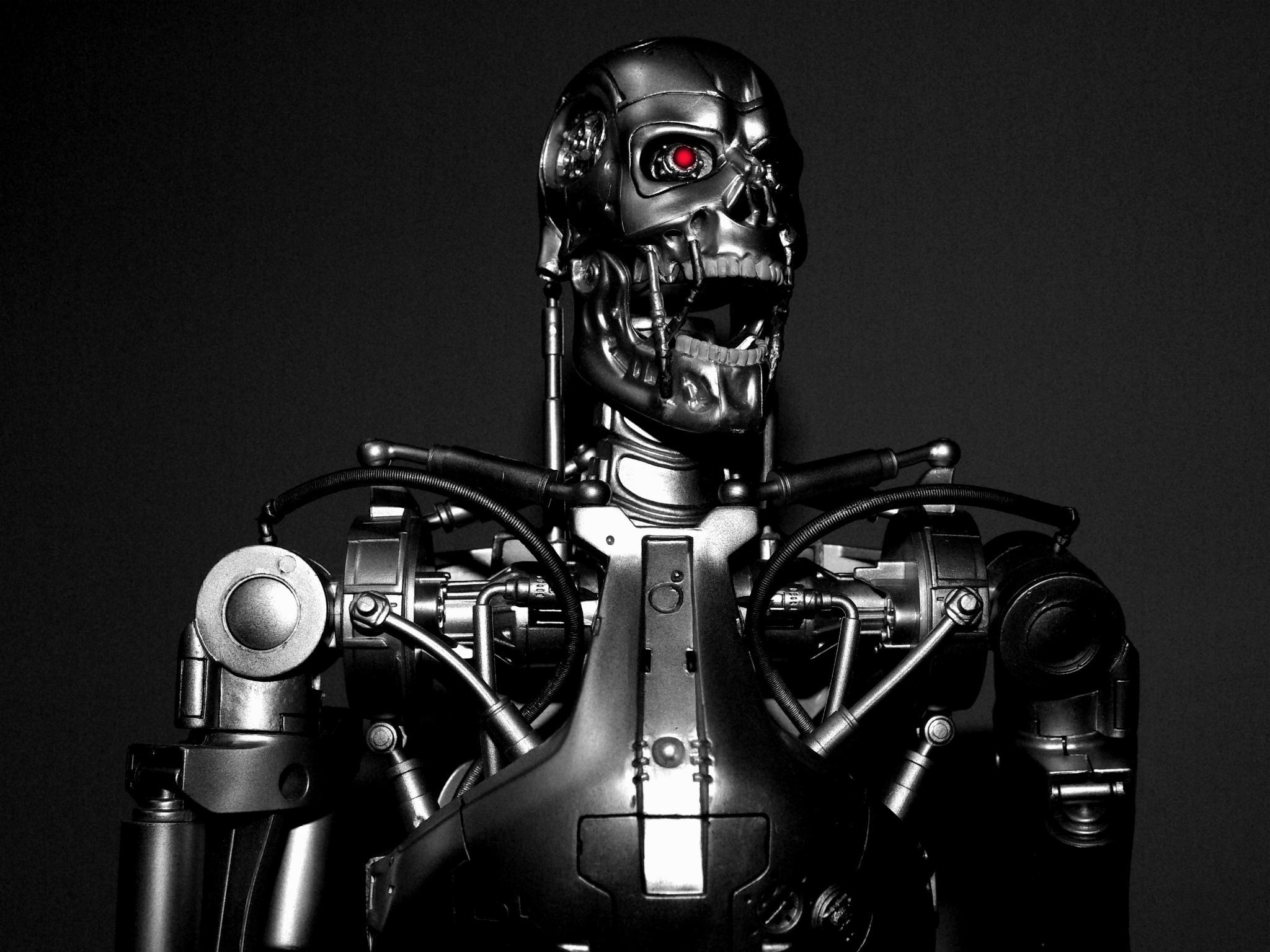

Artificial intelligence

2045. This is the year that renowned futurist Ray Kurzweil predicts the technological singularity will take place – the moment when computers surpass human intelligence and continue to improve at an uncontrollable rate, signalling the end of the human era. “The pace of change will be so astonishingly quick that we won’t be able to keep up,” Kurzweil warned in his seminal book on artificial intelligence in 2005, The Singularity is Near, which brought the technology from the realm of science fiction fears, to real-world ramifications.

Kurzweil has since taken up a position at Google, the company some leading AI experts believe is winning the race to create human-level artificial intelligence. One of the reasons for this is the technology giant’s acquisition of DeepMind in 2014 – arguably the world’s leading AI company. With the vast resources of Google at its disposal, DeepMind has since surpassed key milestones leading towards the singularity, such as beating human champions at the vastly complex board game Go.

It is too early to judge the accuracy of Kursweil’s prediction (of his 147 predictions since the 1990s, he claims an 86 per cent accuracy rate), though the advances made over the last two decades mean his concerns may soon no longer be simply hypothesis. He is now joined by some of this century’s brightest minds in warning of the existential threat that AI continues to pose to humanity. AC

Amazon

Amazon has been referred to as the everything store. And it’s now the everywhere store: not only the internet’s central marketplace, and a disruptive force that has changed what people expect from internet shopping, it is now also the underpinnings of the internet itself.

The way Amazon has changed shopping is profoundly important, of course. By offering the ability to buy just about anything you want online and have it arrive quickly, it precipitated a revolution both in online shopping and on the high street.

Because the online shop is only the most obvious part of Amazon. It’s internet infrastructure underpins much of the web; Alexa is the leading light of the smart home and voice assistant revolution; it owns real shops including Whole Foods; its decisions over things like locations and taxes are like government policy only bigger. Over the 2000s, Amazon came to own much of the internet, and technology’s future will decide what it does with it. AG

Skype

Before this century began, making long distance phone calls was a costly and frustrating endeavour. Voice delays were an accepted part of calling between different time zones and conversations between participants had to be significantly adapted in order to not interrupt or talk over each other.

All of this changed when Skype appeared in 2003. The internet had already brought the possibility of cheap international calls, but Skype’s technology brought high-quality calls that were completely free.

Its growth was astonishing. It took just 10 years to reach 300 million connected users – a feat that took the mobile phone 25 years, and the traditional telephone 104 years. It has also reached that rarefied tech territory shared by the likes of Google and Xerox, whereby its name has outgrown it and is now a commonly recognised verb.

Skype inspired important imitators like Apple’s FaceTime and WhatsApp’s video call function, all of which have continued to make the world smaller with a combined user base of billions. AC

Wikipedia

One of the early promises of the internet was to provide the world with free and easily accessible information. With the possible exception of Google, nothing has fulfilled this quite like Wikipedia.

Founded by Jimmy Wales in 2003, Wikipedia was not the first online encyclopedia. It was not even the first online encyclopedia created by Wales. Three years earlier, he had helped found the peer-reviewed encyclopedia Nupedia, which was free to use but had strict controls on who could post.

Wikipedia opened this up by adopting the concept of wiki – a collaborative form of website whereby users work together to create it. By allowing anyone with an internet connection to contribute content and make edits, Wikipedia was able to grow at a rate that would have previously been inconceivable. Nupedia’s laborious seven-step approval process had seen just 21 articles published in its first year. In Wikipedia’s first year, more than 18,000 had been published.

The English-language version alone of the ever-evolving information resource now has more than 5 million articles – and all of it completely free and easily accessible. AC

Robotics

In the year 2000, the world was introduced to Asimo: a humanoid robot created by Honda that astounded onlookers by descending some stairs to enter a conference. It was to be the first in an impressive line of increasingly evolved bi-pedal robots that are now capable of tricks most humans can’t even do – from performing backflips, to visiting space.

After decades of nebulous developments into robotics in the 20th century, real-world uses are finally being found in everything from recycling, to caring for the elderly. A mesh of other new technologies, like virtual reality and 5G, mean it is now possible to remotely control robots in real time – though it may take another few years for the implications of such technologies to be fully realised.

When they are realised, the advances made in the early 21st century could pave the way for robots exploring the outer reaches of space on behalf of humanity. AC

Biometrics and surveillance

In hindsight, George Orwell’s prophetic warning in 1984 that ‘Big Brother is Watching You’ seems relatively naive. Sure, there are CCTV cameras on nearly every street corner of the UK, but technology’s invasiveness is far more pervasive. We now invite listening devices into our pockets and cameras into our homes, all in the hope that our lives will be slightly more convenient and occasionally less lonely.

In 2010, Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg declared that the age of privacy is over. He said in an interview that privacy was no longer a “social norm”, and the billions of people signing up to his social network seemed to attest to this. But subsequent data scandals with Facebook and the rise of advanced facial recognition software has seen a recent push back against the steady erosion of privacy.

Just as technology has heralded a new era of surveillance, it has also enabled new forms of privacy, like virtual private networks (VPNs) and encryption software. These will be among the weapons in the fight to prevent an Orwellian dystopia from being realised. AC

Always-available maps

Perhaps the most underrated technological development of the 2000s is that the idea of getting lost has been made obsolete. Services like Google and Apple’s maps made every part of the world viewable and navigable from above. Others like Waze and Citymapper introduced rich data that make journeys faster and smarter.

With the development of those apps, getting around has changed fundamentally. They have come alongside other changes like the availability of small vehicles such as scooters that are distributed around towns, and the promise of smart and self-driving cars. We possess a wealth of information on where we are and where we are going that previous generations could never have imagined, and it is being used in ways that will rewrite both real and virtual landscapes.

Location data is some of the most valuable on offer to technology firms, and companies like Google and Facebook have faced questions about what they gather on users and why. But it is so useful precisely because it is so personal; it offers great value to us, too. AG

[This article was originally published in December 2019]

Related: To find the best iPhone offers around, try our comparison page on the best iPhone deals.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks