Portrait of the artist as a bitcoin: When cryptocurrency meets conceptual art

The artist Kevin Abosch has turned himself into a coin by stamping blockchain tokens in his own blood

Kevin Abosch wanted to turn himself into a coin. Why? Because he sold a photograph of a potato. Let’s back up.

Abosch, 48, is an Irish conceptual artist and photographer who lives in New York. He is also interested in the blockchain, the technology best known for its use in virtual currencies like bitcoin and ether. The strange culture surrounding these cryptocurrencies is increasingly making its way into art, in works that explore value, decentralisation and the buzz around digital money.

Which brings us back to Potato #345, a photo that made headlines around the world after Abosch said it was purchased by a European businessman in 2015 for €1m. On the one hand, the attention generated by the sale was exciting, he said. “On the other hand, the focus shifts from the artistic value to monetary value of the work – and for most artists the art is an extension of the artist, so you yourself start to feel commodified,” Abosch says. “In order to sort of control that, I began to think of myself as a coin.”

Abosch turned to the blockchain, which essentially records a series of transactions across a large, open network of computers. The ethereum blockchain allows coders to create virtual tokens, which can be transferred between users. They are not always currencies, exactly, but something like them.

Abosch created 10 million tokens in January. “But I didn’t want to just make these 10 million pieces of virtual art,” he says. “I wanted them to be connected to my body.”

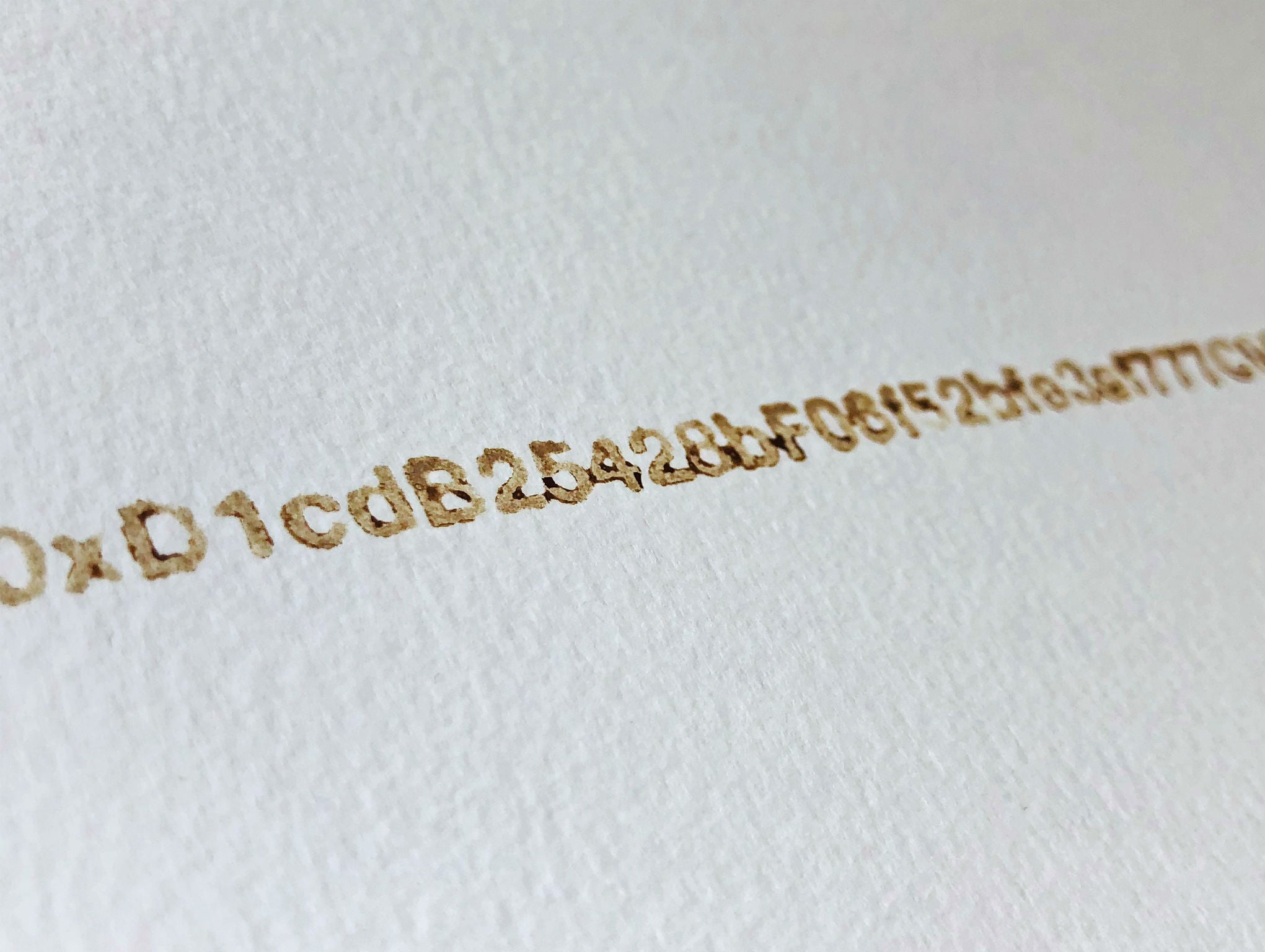

So he had six vials of his blood drawn. He stamped the contract address – a long string of numbers and letters indicating where the tokens effectively live on the blockchain – onto 100 pieces of paper, in blood. And he called the project IAMA Coin. He says he believes that he has “successfully connected my physical body to the virtual works” in such a way that he sees the art “as pieces of me”.

Michael Connor, the artistic director of Rhizome, a centre affiliated with the New Museum that aims to foster “digital-born art and culture”, says that he has seen a flurry of crypto-related projects in the past year.

“Blockchain seems like it has some sort of potential to offer a different economic logic that structures society, and so a lot of artists are interested in the social implications of blockchain and crypto,” he says

Abosch’s works – and how they are bought and sold – capture some of the strange ethos of the world of cryptocurrency. A former tech executive recently paid more than the price of a real Lamborghini for a neon sculpture Abosch made of a blockchain address that symbolised Lamborghinis.

The piece, YELLOW LAMBO (2018), made news much like Abosch’s potato photo did. (The marriage of conceptual art, capitalism and the internet is a reliable generator of “How can this be?” headlines.) The work is a reference to a half-serious joke in the crypto community about using profits to buy Lamborghinis.

“I became familiar with #lambo as a declaration of success-identity – and because I always think in terms of how to distil emotions around value, I wanted to explore that,” Abosch says. He created another token, called YLAMBO, and turned its address into a physical sculpture in yellow neon. This sculpture then sold for $400,000 at a San Francisco art fair to Michael Jackson, the former chief operating officer of Skype.

The meta-weirdness around the purchase of the art is at the heart of the questions Abosch wants to explore.

“You meet people in the crypto world who throw millions into coins backed by nothing, but don’t understand how a piece of art has any value,” he says. “Then you meet people in the art world who don’t understand why you would invest money in art that has no physical manifestation. That’s where it gets exciting for me.”

He has a foot in both the art and tech worlds, and experiments with their intersection. As he works, Abosch has been wearing an electroencephalogram, or EEG cap, which can measure electrical activity in the brain. He wrote in an email that this is “an attempt to understand to what extent ego is engaged or how it colours work, particularly when I’m photographing humans”.

He added: “I have a sense that my ego is disengaged at the moment I press the shutter release, but this is just a theory.”

Some of Abosch’s work has no visual presence whatsoever. Forever Rose, although inspired by a photograph of a flower, exists only as a single blockchain token that sold to 10 people in February for a total of $1m. Abosch says this seems to him “the purest form of art –it’s the idea, without the baggage of a vessel”.

He says wryly: “When I get pushback sometimes from people, I suggest they might have an unhealthy relationship with the material.”

To some, these projects might seem like stunts. But the art world is starting to take them seriously. An extension of Abosch’s IAMA Coin, titled Personal Effects, recently showed at the State Hermitage Museum in St Petersburg, Russia. And at a recent Rhizome conference, Seven on Seven, three crypto projects were unveiled, Connor says. In one, two artists played with the idea of uploading a religion onto the blockchain.

“I think that it’s such a weird field at the moment, so art is evolving really quickly in response to it,” Connor says.

Abosch, meanwhile, is tokenising Manhattan. For a soon-to-be-unveiled project, he has created 10,000 blockchain tokens for every street in Manhattan, then printed the contract addresses on a 6ft tall map. This month, collectors will be able to buy the tokens, or virtual artworks, for a few dollars each. More projects are on the way.

“Whatever this is,” Abosch says, “I’m right in the middle of it.”

© The New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks