Controversial 'three-parent baby' technique given go-ahead in historic decision

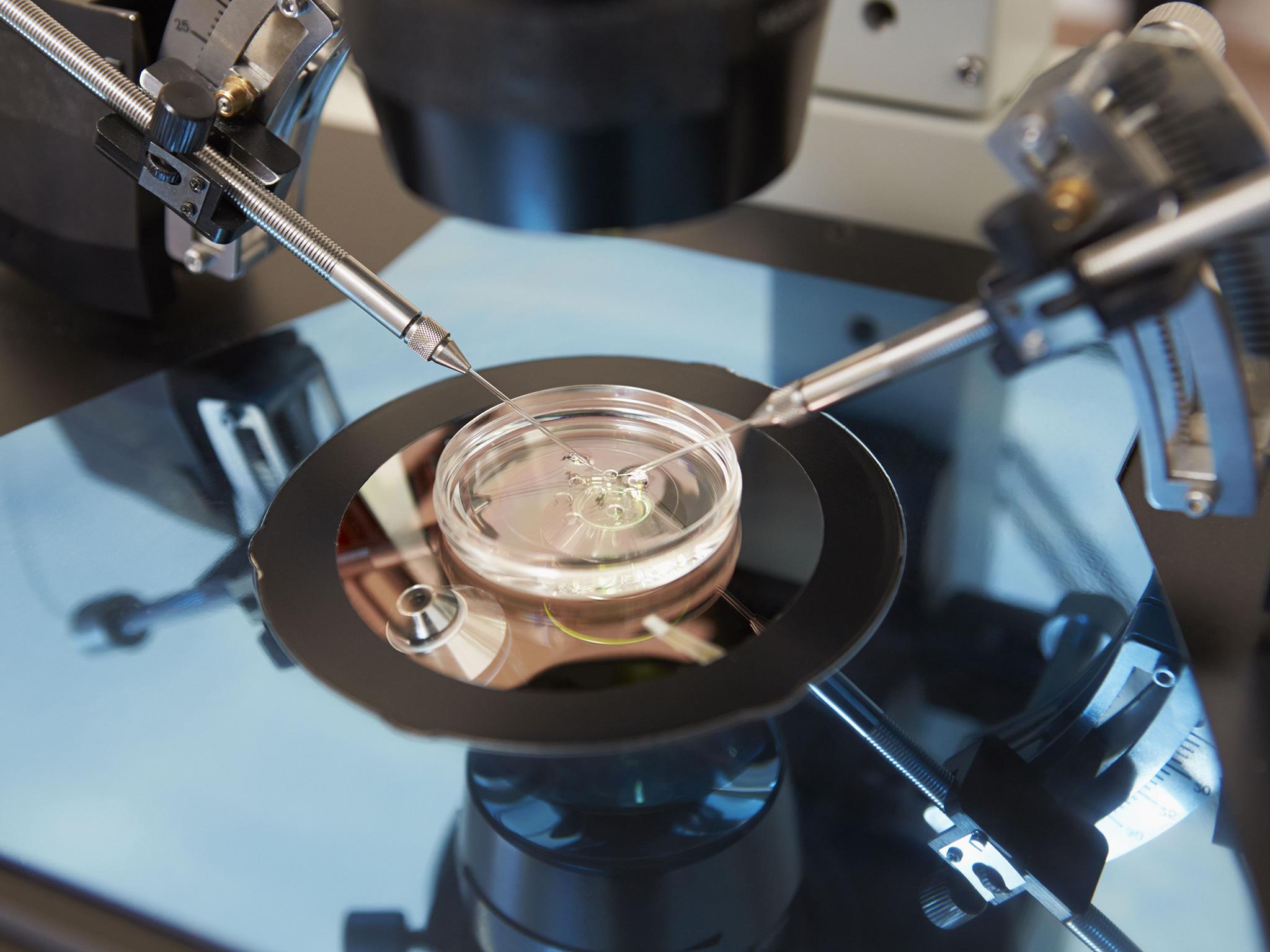

Three-person IVF can prevent babies from inheriting deadly genetic diseases

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The first ‘three-parent’ babies could be born in the UK next year following a historic decision giving the controversial new fertility technique the final go-ahead.

Three-person IVF, which prevents babies from inheriting lethal genetic diseases, has been approved by fertility regulator the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority (HFEA).

Babies born using the technique would receive a tiny amount of DNA from a third woman in addition to genetic information from its mother and father.

Last year the UK became the first country to legalise mitochondrial replacement therapy (MRT), as the technique is known.

The HFEA’s decision means clinics are now free to apply for permission to carry out the treatment, with the first patients expected to be seen as early as next Spring.

Professor Mary Herbert, who has led scientists pioneering the technique at Newcastle University, called the decision “enormously gratifying”.

“Our many years of research in this area can finally be applied to help families affected by these devastating diseases,” she said.

According to the team, MRT is scientifically ready and they already have women lined up to receive the therapy.

They hope to treat up to 25 women a year and NHS England has said it will provide £8m of funding to a five-year clinical trial.

Every patient would have to be considered separately before a licence allowing the therapy is issued by the regulator.

HFEA chair Sally Cheshire said the decision was “of historic importance”, the BBC reported.

She said the decision was “about cautious go ahead, not gung-ho go ahead” and added there was still a “long way to go”.

One in 200 children are born with faulty genes in their mitochondria, small structures inside cells that generate energy.

This can lead to a wide range of potentially fatal conditions affecting vital organs, muscles, vision, growth and mental ability.

Just 0.1 per cent of a person’s DNA is held in the mitochondria. It is always inherited from the mother and has no influence over individual characteristics such as appearance and personality.

An independent panel of experts has recommended “cautious adoption” of MRT, which is carried out by transferring the genetic material that effectively encodes a baby’s identity to a donor egg whose own nuclear DNA has been removed.

Two different techniques may be employed, either before or after fertilisation. The end result is the same – an embryo containing healthy mitochondria from the donor and nuclear DNA from the baby’s mother and father.

In theory, mitochondrial replacement can not only prevent a child developing inherited diseases, but also protect future generations.

Critics say the technique is not foolproof and small numbers of faulty mitochondria may still be “carried over” into the child, and even replicate in the developing embryo.

Others believe the procedure is tantamount to genetic modification of humans or even “playing God”.

They also argue that unforeseen problems might occur once the procedure is used to create human babies. For instance, replacing mitochondrial DNA might have more of an impact on personal traits than has been envisaged.

Unknown epigenetic effects – environmental influences that alter the way genes work – may also have serious consequences for the health of babies, it is claimed.

The world’s first child created using the “three-parent baby” technique was born in Mexico earlier this year.

The baby’s parents are from Jordan and the work was carried out by a team of experts from the US.

The child's mother has Leigh syndrome, a fatal disorder that affects the developing nervous system and would have been passed on in her mitochondrial DNA.

The technique used by Dr John Zhang, of the New Hope Fertility Centre in New York, and his team involved taking the nucleus from one of the mother’s eggs – containing her DNA.

They then implanted the nucleus into a donor egg that had its nucleus removed but retained the donor’s healthy mitochondrial DNA.

Dr Zhang told the New Scientist that, as the technique has not yet been approved in the US, the team went to Mexico where “there are no rules”.

“To save lives is the ethical thing to do,” he added.

Professor Frances Flinter, consultant and professor of clinical genetics at Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust, said he was “delighted” by the decision.

“This is wonderful news for families who have, in some cases, waited years or even generations for the chance of having a healthy baby,” he said.

“Mitochondrial disorders can be very serious, progressive conditions and some couples know that they will never be able to have a healthy child of their own without trying this new therapeutic approach.”

But Trevor Stammers, a lecturer at the catholic St Mary’s University in Twickenham, London, said a “truly cautious” approach would be to monitor the health of the child born in Mexico before carrying out the procedure in the UK.

Professor Sir Mark Walport, the Government’s chief scientific adviser, said he welcomed “this careful and considered assessment by the HFEA”.

“The UK leads the world in the development of new medical technologies. This decision demonstrates that, thanks to organisations like the HFEA, we also lead the world in our ability to have a rigorous public debate around their adoption.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments