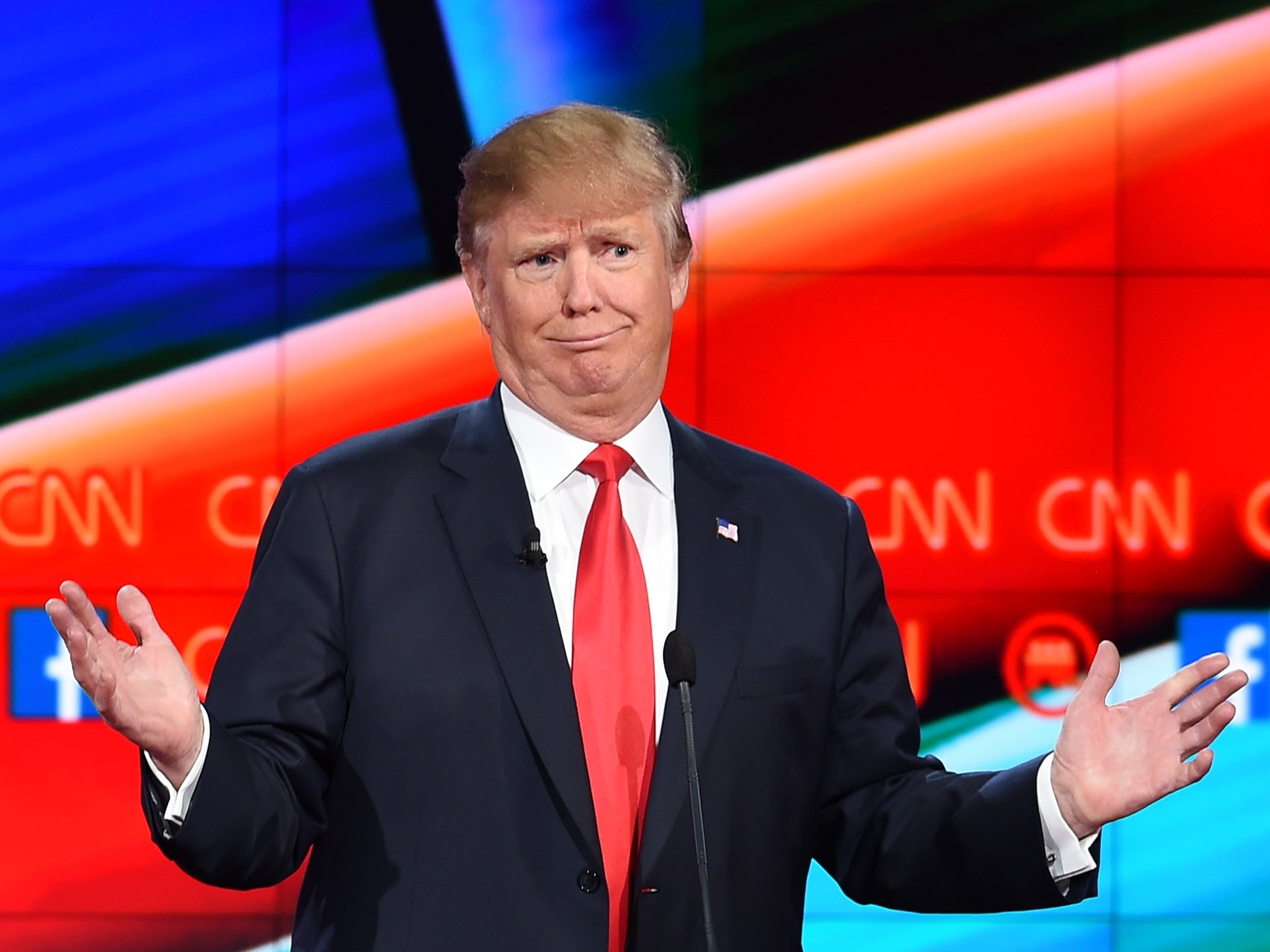

With Donald Trump a potential president and an EU referendum looming, 2016 is looking distinctly ominous

Though it is still more likely than not that the people will vote for the status quo in the EU referendum

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.For anyone with an internationalist outlook, 2016 is looking distinctly ominous. In November, the US could elect a president who will be a disaster for international co-operation. If you thought George W Bush’s hostility towards the United Nations was destabilising, just wait until Donald Trump is in charge. His candidacy has gone from being a joke to one that seems to be propelled forward by a galloping inevitability. Then there is the growing prospect that the EU referendum, which could come as early as June, will result in Britain’s exit from the European Union.

It is still more likely than not that the people will vote for the status quo – this is what happened in Scotland, after all. Yet the story of the independence referendum is echoing through this EU campaign today. The same mistakes are being made, with the same outcome on the cards: a dangerously close vote.

David Cameron has plenty of critics of his EU renegotiation strategy, so I won’t add to them. In any case, the Prime Minister was always going to be in a position where he, as we northerners say, can’t do right for doing wrong. For example, the pro-Brexit former Chancellor Nigel Lawson said back in June 2014 that Cameron would get nothing out of renegotiation. The anti-EU camp were always going to cry foul, no matter what the PM did.

Instead, let’s look at Labour’s role and responsibility in this referendum. As with Scotland, Labour being in opposition seems to lull its politicians into a diffusion of responsibility. Of course, they wanted to fight for the Union, just as many of them want to fight to remain in the EU. But there is a sense that, as with Scotland, if the worst happens, they can blame the Prime Minister for losing the vote on his watch.

With some honourable exceptions, including Jim Murphy, Labour’s fight in Scotland was slow – it came just in time to save the UK but was too late to save their own seats. Their campaign was based on fear of what might happen under independence, in stark contrast to the positivity of the “yes” side.

Similarly, Labour’s “in” campaign, as talented as its top names, such as Alan Johnson and Chuka Umunna, are, is dwelling on a fear of Britain’s isolation outside the EU and warning that exit will make us less safe from terrorists, rather than what our country gains from membership. Any positive arguments are pitched at a macro, ideological level, which has little relevance to voters in, say, Morley and Outwood who voted for Ed Balls in 2010 but turned away from Labour in 2015.

As our political editor, Tom McTague, reveals, if Labour had pledged an in/out referendum at the general election it could have saved the party eight seats, including Morley and Outwood, which would have been enough to deny the Tories an outright majority. Sounding a note of Euroscepticism would have been in tune with the voters, particularly in northern working-class constituencies. Balls and Labour’s policy chief, Jon Cruddas, wanted Ed Miliband to back a referendum, but he refused.

In this sense, it is Jeremy Corbyn – who despite pledging to campaign for an “in” vote is known to be Eurosceptic – who is in closer touch with voters. Labour’s “in” chiefs need to acknowledge that people are concerned about the effect on their wages and livelihoods as a result of EU immigration. The argument in favour of Europe must not be cast in post-war settlement terms, nor must it be a repeat of the scaremongering that we saw in the Scottish referendum in 2014. Without a positive, ground-level case for EU membership, Labour risks assisting Brexit. The responsibility is theirs as much as it is the PM’s.

The lady was for darning

Of the hundreds of items owned by Margaret Thatcher that were sold at auction last week, the top-selling pieces were unsurprising: her red box and a model of a bald eagle given to her by Ronald Reagan. But to me the most fascinating item was her raffia sewing basket with many compartments and an accompanying set of button boxes. These sort of sewing baskets have always fascinated me, from the moment I found myself picking through the pins and thread of my mother’s wicker basket, with its hidden pockets and scraps of tartan material, at the age of five. I am not alone, it seems: a bidder paid more than £3,000 for her sewing basket, the same as a pair of silver-gilt goblets. This basket was a hitherto unknown part of the former Prime Minister’s estate, although she made great play of her role as a housewife in Downing Street. The sale, which raised more than £4.5m, has helped to cement her image as a matriarch of the country, rather than the divisive, hated figure she was to many.

Tale of two speeches

The woman who wants to emulate Thatcher, Theresa May, spoke to women political journalists at a lunch in Westminster last week. She was asked about two of her most famous speeches: the first, to the party conference in 2002, in which she enraged activists by describing the Tories as the “nasty party”, and the second, her speech at this year’s conference which took a tough line on immigration. At lunch, the Home Secretary claimed the party’s nasty image no longer applied, and insisted that the Mark Clarke bullying scandal had not set back this rehabilitation. She also lamented that a part of her 2015 speech, in which she called for greater protection of genuine refugees, had been lost.

A bad career move

Yet, even as May spoke, the revelations about fellow Tory MP Lucy Allan ranting at a young staffer were breaking. Of course, bullying is not confined to one party. But both the Allan and Clarke cases are causing alarm in Downing Street. It is difficult to see how the political career of Allan, who was recorded calling Arianne Plumbly “pathetic”, can survive. I am sure this sort of bullying behaviour goes on all the time, particularly among self-absorbed MPs. What is unusual is for us to hear it. I hope it gives the next bully a reason to reconsider their behaviour in case they are being recorded.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments