This is how we are creating the richest one per cent

According to Oxfam, the wealth of the richest one percent is equivalent to the rest of the world’s combined. This is the result of a system which allows the rich unfettered representation without taxation

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In the 12 months since Oxfam hit the headlines warning that the global 1 per cent would soon own more than everyone else on the planet put together, inequality has been at the centre of domestic and global political debates.

Cabinet ministers such as Michael Gove and world leaders ranging from President Obama to Christine Lagarde and the Pope have warned of the dangers inherent in the yawning gap between those struggling to get by and what Mr Gove described as the sometimes “undeserving rich”.

Our leaders, it seems, are catching up with US commentator, Thomas Frank, who remarked during the 2008 financial crisis: “Massive inequality, we have learned, isn’t the best way to run the economy after all. And when you think about it, it’s also profoundly ugly.”

But instead of healing the scars on the face of the global economy, the last 12 months have seen fresh wounds appear as the richest have pulled further away from the rest of us.

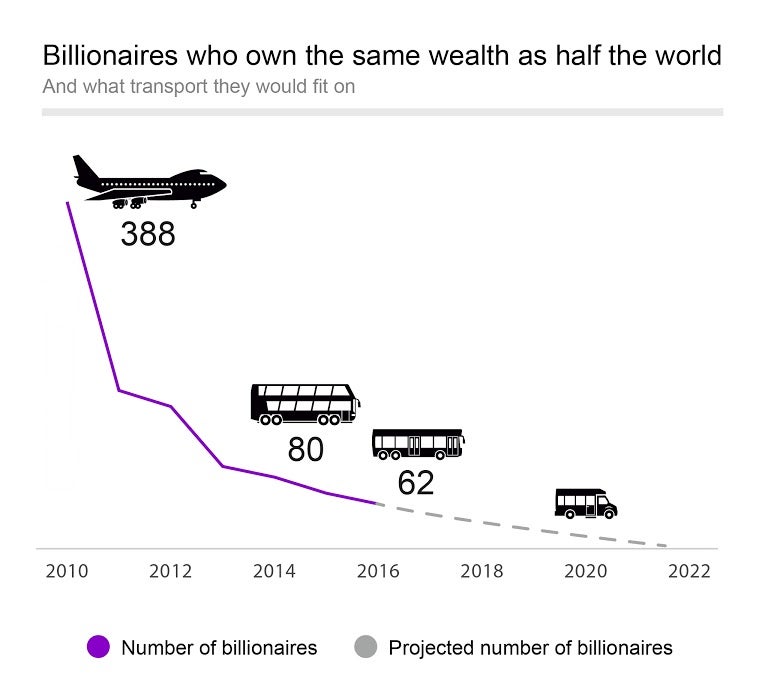

Our latest report published today, confirms that in 2015 – a year earlier than we had predicted – the combined wealth of the 1 per cent overtook that of the remaining 7.2 billion people on the planet. Perhaps even more strikingly, the richest 62 people on the planet – a number you could fit on a coach - now own more than the poorest half combined.

To get some idea of the widening gap consider that a year ago the figure was 80 (you’d have needed a double-decker bus to transport them) and as recently as 2010 it was 388 (too many for an Airbus 340 but you could have got them on a Boeing 747).

Ah, I hear you say, these folk from Oxfam mean well but they’ve picked the wrong measure, a rising tide lifts all boats and if the yachts rise faster than the rafts then that’s a price worth paying when we’re all better off. Didn’t you put an advert on telly proclaiming that poverty has halved in the last 15 years and that in the next 15 the world can end it?

Yes we did, and yes we do believe that world leaders have a chance of meeting their September promise to end extreme poverty by 2030. We all recognise that investment, trade and profit are essential to economic development and our goal of eradicating poverty. But the truth is that we won’t be able to reach that goal unless we tackle extreme and widening inequality.

While Oxfam celebrates the fact that millions of people have escaped extreme poverty, the daily incomes of the poorest 10 per cent have risen by less than a cent a year on average during the last quarter of a century. And the fact is that since 2010, the wealth of the poorest 50 per cent has fallen by a trillion dollars. During the same time the wealth of the richest 62 has increased by half a trillion. If the poorest 40 per cent had shared in even the average economic growth of their countries over the last twenty years there would be 200 million fewer people living in extreme poverty today.

Instead of trickling down to the poorest as economists promised, wealth is being sucked up to the top. To understand why, we need to look beyond textbook economics and take account of the fact that the wealthy have more resources and opportunity to influence policy makers and are therefore more likely to benefit from laws, regulations and economic policies and practices that favour their interests.

This can be seen in the explosion of executive pay, accompanied by reductions in taxes for top earners, while wages for so many others, especially the already low paid have stagnated or fallen. Low pay disproportionally hurts women. It can be seen in the growth of the financial sector – which now accounts for one in five billionaires globally but survived in its present form thanks to government bailouts when its bets went bad. Perhaps most of all it is reflected by the fact that we are condoning tax havens which allow the richest individuals and biggest multinationals to avoid paying their fair share to society.

As Jim Kim, World Bank President, said last year, tax dodging is a form of corruption. It is one that hurts all of us who rely on the state for our healthcare, schools and other vital public services. It is people who are poor, sick and hungry who suffer most.

Almost a third of all African financial wealth is estimated to be held in tax havens which can only operate thanks to the indulgence of rich countries’ political leaders. This costs African governments an estimated $14 billion in lost tax revenues every year, enough to pay for healthcare for mothers and children that could save 4 million children’s lives a year and employ enough teachers to get every African child into school.

It is time to end the era of tax havens, and the UK – which via its Crown Dependencies and Overseas Territories is responsible for a third of the world’s offshore centres - has a leading role to play. At Davos three years ago, David Cameron promised to make tax dodgers ‘wake up and smell the coffee’. Yet his subsequent promise that the Cayman Islands, British Virgin Islands and other remnants of the British Empire would lift the veil of secrecy surrounding company ownership – a vital step towards curbing such activities – has been allowed to founder. The Prime Minister urgently needs to revisit his promise ahead of the global anti-corruption summit he will host in May.

To close the gap between rich and poor, governments around the world need to tackle the problems of poverty pay, so that those who work earn a living wage, must invest in public services which can disproportionately assist the poor, must look at the gaps between men and women, and offer more support to those who cannot work to ensure the poorest as well as the richest benefit from economic growth. They also need to take on the vested interests which defend tax havens and extreme tax avoidance. Too many of the rich and powerful today have unfettered representation but virtually no taxation.

Mark Goldring is Chief Executive of Oxfam GB.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments