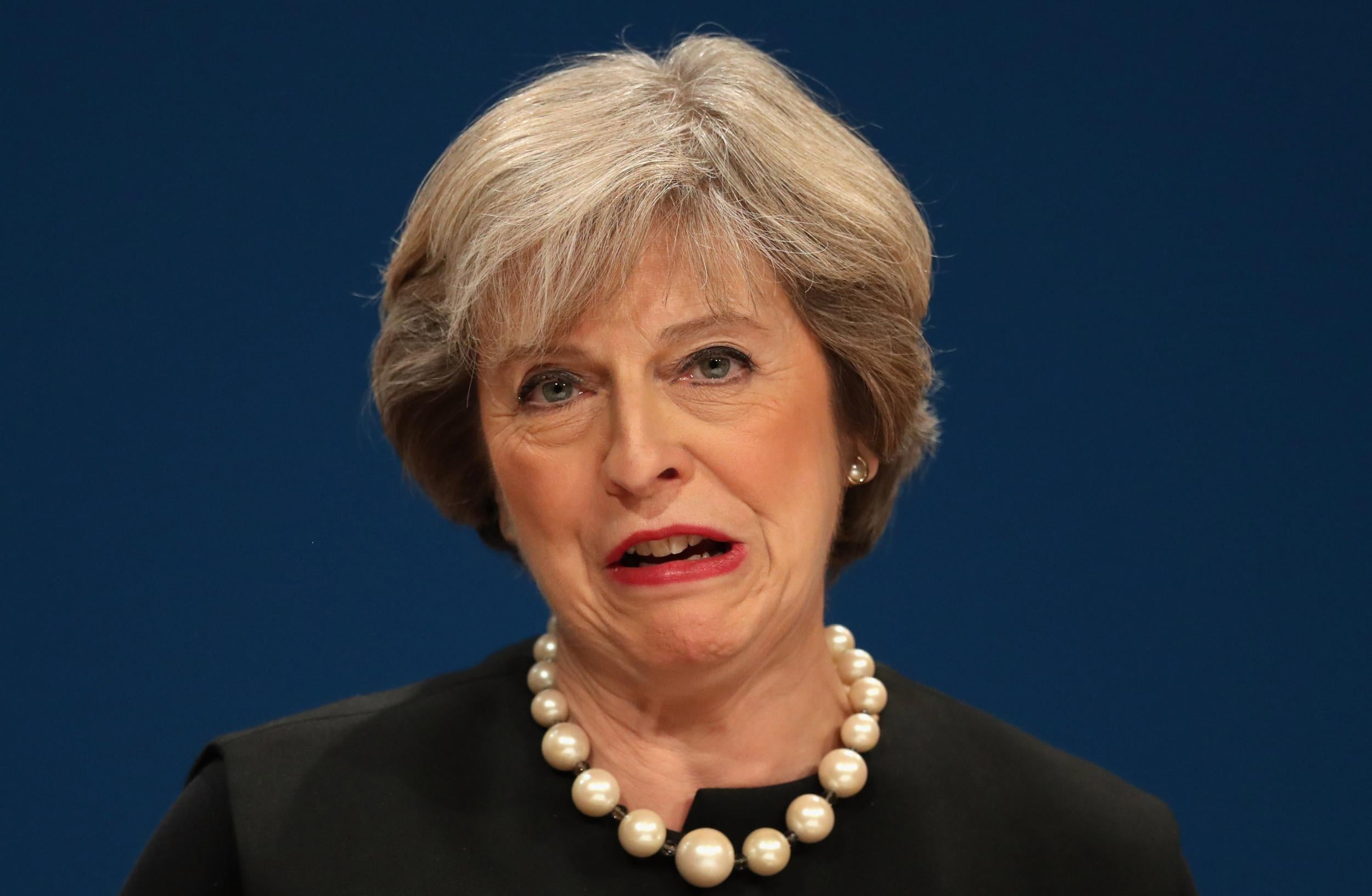

Theresa May will probably get a good Brexit deal, but nobody can say so

There is no way that the Prime Minister could contemplate doing something as stupid as setting out in Parliament what she hopes to obtain in Brexit negotiations

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Theresa May cannot do what the Remainers want her to do, namely to set out the kind of deal she hopes to reach with the European Union when we leave. This week there were two debates in the House of Commons on Brexit – David Davis, the Brexit Secretary, made a statement on Monday, and Labour used one of its opposition days to debate it on Wednesday.

On both occasions, the two opposition parties, Labour and the Tory Remainers (led by Kenneth Clarke, Anna Soubry, Nicky Morgan and Dominic Grieve), demanded that the Prime Minister put her negotiating stance to the Commons for scrutiny and possibly even a vote.

There is no way that she could contemplate doing something so stupid. Suppose she said, for example, that the Government wanted Britain to remain a member of the single market but with an emergency brake on immigration. Suppose, further, that she didn’t get what she wanted. Which she wouldn’t, because Angela Merkel, François Hollande, Jean-Claude Juncker and Donald Tusk have all said that the “four freedoms” are inviolable. One of those is freedom of movement.

Never mind that Norway and Liechtenstein, to name two countries that are members of the single market but not of the EU, have some kind of exemption from freedom-of-movement rules,* the EU’s leaders are not going to give the UK an opt-out. If they did, as some of the more open German politicians have said, everyone would want one. (“We cannot give them any concessions because others will then demand the same,” said Thomas Oppermann, parliamentary leader of the Social Democrats, Merkel’s coalition partners, in July.)

We went through this with David Cameron’s renegotiation in February. He wanted an emergency brake; Merkel made it clear privately she wouldn’t give it to him; so he didn’t ask for it. In the closing stages of the referendum campaign, as he panicked about losing, he thought of asking for it again as a last-minute concession that would keep Britain in the EU. But he decided not to – for the same reason that May won’t ask for it now. He thought Merkel would still say no; his request would be leaked; he would be humiliated. That, he calculated, would be more damaging than failing to try. And he was right. Merkel confirmed to him afterwards that she wouldn’t have given him the brake. Maybe she was just trying to make him feel better about losing the referendum, but I don’t think so.

So Theresa May cannot announce to Parliament that she is aiming to get x or y in her Brexit negotiations. If she doesn’t get them, she will look foolish or weak. The most she can do, as Cameron did, is to try to sound out European capitals and Brussels bigwigs privately to see what sort of deal they might be prepared to accept. Even that is fraught. Just on the simple question of when she is planning to trigger Article 50, the formal two-year process for leaving the EU, various private conversations have leaked.

In the end, as the Tory Remainers pointed out this week, she didn’t even consult the Cabinet before making the announcement at the Conservative Party conference that she would trigger Article 50 by the end of March. This is not a constitutional outrage, it is a fact of modern politics. If she had told the Cabinet – no one is so naive as to imagine that Cabinet could have had an open-ended discussion about such a subject – it would have leaked.

The Prime Minister has to manage expectations. She has to prepare the nation for the hardest of Brexits so that any tariff-free access to the single market, any agreement on common standards, or any reduction in our contribution to EU funds, can be presented as a negotiating triumph.

Paradoxically, the EU’s leaders share Theresa May’s interest in playing down expectations of the Brexit negotiations. They cannot allow the sceptical peoples of Denmark, Sweden, the Czech Republic and even the Netherlands to think that the grass might be greener outside the EU. Hence Donald Tusk, the EU President, showing that he has quite a neat turn of English phrase in his speech on Thursday, made fun of Boris Johnson’s “cake philosophy”. To all who believe in it, he said, “I propose a simple experiment. Buy a cake, eat it, and see if it is still there on the plate.” In his opinion, “the only real alternative to a ‘hard Brexit’ is ‘no Brexit’”.

EU leaders have obviously decided that they cannot be seen to be rewarding the UK for leaving the club, but when it comes to the negotiations there are – as the Leave campaign pointed out during the referendum – the interests of German car makers to consider.

So May and Tusk both start the talks next year by assuming that Britain will be out in the coldest trade tundra – any mutually beneficial agreement will come as a bonus to be trumpeted over here and to be played down in front of an EU audience.

This lowering of expectations gives Labour a great opportunity. I said last week that Keir Starmer’s appointment as shadow Brexit Secretary would be the making or breaking of him. On The Andrew Marr Show last Sunday and in two Commons debates, he made an impressive start. He aligned Labour with the Tory Remainers’ demands for parliamentary scrutiny of Brexit without quite admitting that Labour’s position was similar to the Government’s. He said immigration should be reduced, which rules out Britain being part of the free-movement area, and he said the result of the referendum had to be respected. In Tusk’s terms, then, Labour chooses “hard Brexit” rather than “no Brexit”.

But the advantage of being in opposition is that Starmer can offer the softest Brexit imaginable and berate Theresa May for failing to achieve it. He can say, much as John Smith did in the Commons debates on the Maastricht Treaty, that the Government should have achieved six impossible things in negotiations and that he is disappointed that it failed to do so.

What will happen in 2019 is that May will get a better deal than seems possible now, but that Labour will say it’s not good enough. That is an argument that Labour can win.

*Update: Apologies, I should have made this clearer. Norway and the other countries in the EEA, the European Economic Area (Iceland and Liechtenstein), are allowed to take “safeguard measures” under articles 112 and 113 of the EEA Agreement, “if serious economic, societal or environmental difficulties of a sectorial or regional nature liable to persist are arising”. EEA status, with this measure already triggered to limit immigration from the EU, has been suggested as a transitional arrangement for the UK when it leaves the EU, allowing it to remain in the single market while a permanent relationship is negotiated. I don’t think the EU would agree to it.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments