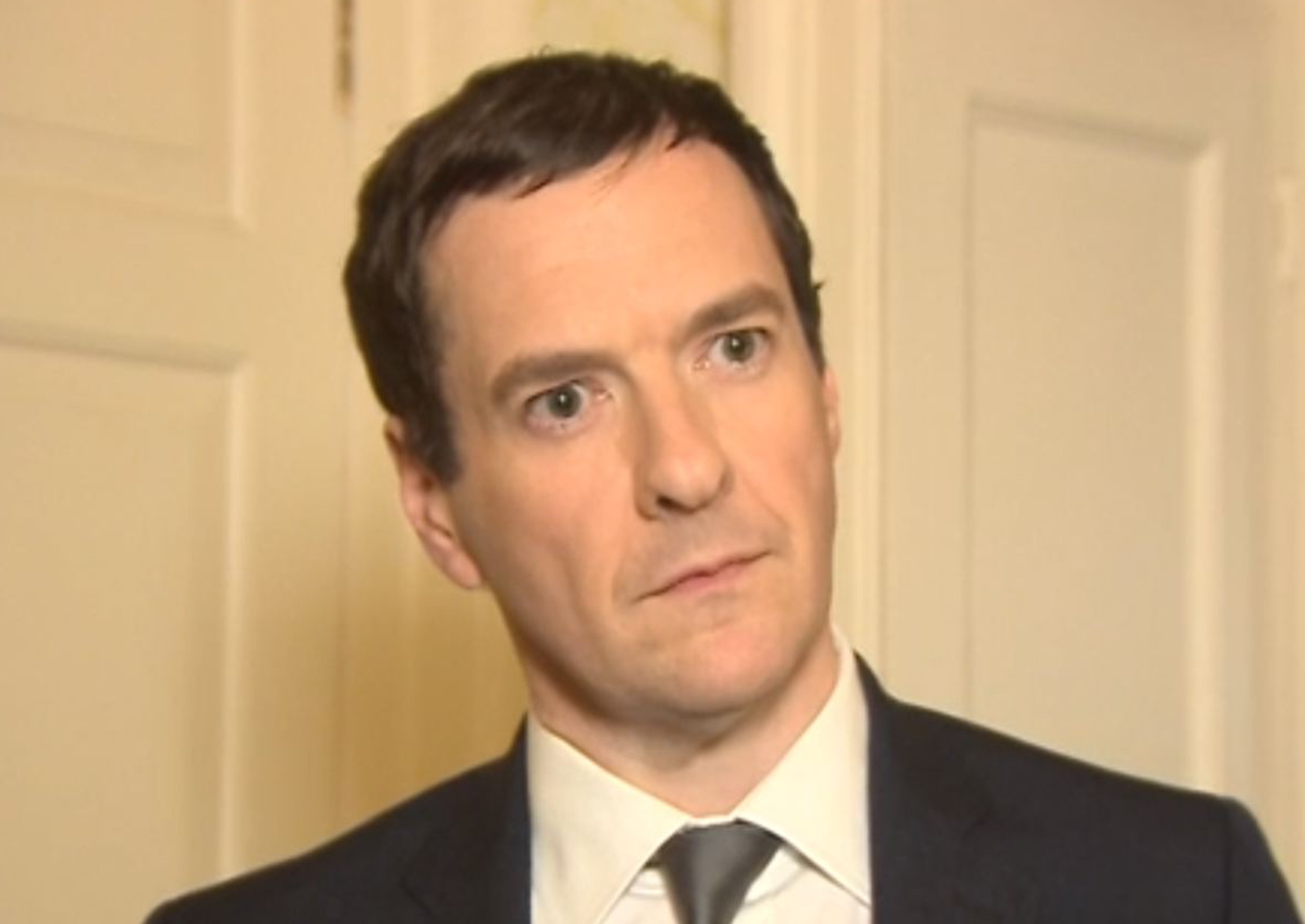

Tax credits do need reform. Here’s where Osborne should start

We can see now that the unintended consequence of the policy was a surge in low-paid jobs

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Step back from the political shenanigans, fun though they were, and focus on the substance. Our system of tax credits is a fundamentally sound idea, introduced by Gordon Brown in April 2003, that after more than a decade’s experience needs reform – as you would expect.

There is the issue of cost, for the scheme has turned out to be vastly more expensive than was predicted at the time. And there is the issue of design, for as so often with government schemes, there have been unintended consequences that have undermined the laudable aims of the project.

Start with cost. When the scheme came in The Institute for Fiscal Studies published an interesting paper, “The New Tax Credits”, explaining the system. There was the child tax credit, the main way in which the Government would support the cost of bringing up children, and the working tax credit, which was designed to make work more attractive for the low-paid.

At the bottom end of the pay scale you cannot make work more attractive by cutting income tax because people aren’t paying it anyway. So you bring in a sort of negative income tax. Just as the tax system creamed off income from high earners, it should bump up income for low earners.

But it is expensive. The cost has not risen from £1.1bn to £30bn as the Chancellor claimed in his July budget, for he is not comparing like with like, as a piece in the latest New Statesman explains. The low figure covered only in-work support during the introductory period of six months, while the high one covers in-work support, support for families with children where no-one is working and replicates support previously given to parents as a tax allowance.

The better figure is the £2.7bn-a-year cost estimated by the Treasury and noted by the IFS. The total cost has not gone up tenfold, because there has been inflation in between, but let’s accept that the cost has gone up about fivefold in real terms. That is a lot, and explained at least in part by weaknesses in its design.

At the risk of over-simplifying a pretty complex system, there has been one key unintended consequence and one key problem with design.

The unintended consequence has been that there has been a surge in low-paid jobs and part of the reason for that is that the taxpayer in practice subsidises employers. People are prepared to work for lower rates than would otherwise be the case because the Government pushes up their pay to a more acceptable level. This is what the whole scheme was designed to do: to persuade more people to go out to work.

But it has, you might say, been much more successful than its instigators expected. The UK economy has become a huge job-creating machine, with 2m more jobs since the recession, sucking in workers from all over Europe. But too many of those are low-paid.

If you ask whether the tax-credit system is also associated with the record rise in participation rates – the proportion of people of working age in some form of work – the answer is almost certainly yes. Indeed some particular groups, such as lone parents, are much more likely to be at work now than in 2000: the proportion there has risen from 51 per cent to 64 per cent. So it looks as though that aim has been achieved.

But there are other areas where it seems to have had the reverse effect. One of these is a family where one partner is at work and the other not. This is explained in a really thoughtful blog by Dr Monique Ebell at the National Institute for Economic and Social Research. (I should disclose that I was until recently on its management council.)

“For many couple families,” she explains, “the tax-credit system makes it more attractive for one partner to stay at home, rather than go out to work. It is this adverse and unintended consequence of the tax-credit system that should be a key focus of any reforms.”

She also notes the problem of timing: “The Government’s proposals withdraw benefits more quickly from all kinds of families as they earn more income. Far from rewarding those on low incomes who work more, the Government’s proposals take benefits away earlier and more quickly from those who work and earn more.”

So the Chancellor has to be cleverer. There are ways of both cutting the cost and improving incentives, and the benefit of this pause for thought should be to use the time to fine-tune the reforms. That and other work by Dr Ebell is not a bad place to start. The key specific points here are that quite aside from containing the costs of the system, we need to do something about the very high marginal rates of taxation that occur when people either move up the income scale, or when the second partner in a family moves into work.

But there is, in addition, a more general point and it is this: we don’t have a very good tax system. If you look around the developed world we are in the middle of the range in the proportion of GDP that the various levels of government raise in tax.

At around 36 per cent of GDP, we are higher than the US, Canada and Australia, but lower than most of the EU. As so often seems to happen we sit between the Anglosphere and Europe.

But this is not about the level of taxation but rather whether the money is being raised efficiently, and the answer here is we are at best the middle of the pack. We are not as inefficient and distorting as the US but we are not top of the class. Our tax code is unusually complicated and becoming more so.

Whenever you make a change in taxes – even if you are just simplifying them – there are winners and losers. So it is much easier to make changes when finances are strong because you have some spare cash to compensate the losers.

Since we still have one of the largest fiscal deficits in the developed world, notwithstanding our solid growth, this might seem a bad time for wider reform. But actually a reform of tax credits could be a start on the road to a better tax system – except that so far, it isn’t.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments