Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.When Confucius was asked by his students what was the first thing he would do if he were made king, the sage replied: “Rectify the names.”

The answer baffled the students, who had expected their master to say he would promote the virtuous into positions of authority and expel corrupt officials. But Confucius explained his reasoning: “If names be not correct, language is not in accordance with the truth of things. If language be not in accordance with the truth of things, affairs cannot be carried on to success.”

In other words, if you don’t first clarify definitions, all else is liable to break down. Clear language is the foundation of clear thinking and coherent action. It’s a Confucian lesson for our own times.

A debate about “capitalism” has flared lately. A survey by the Legatum Institute think-tank showing international disaffection with the concept has generated anguish among the centre-right and provoked a scramble to boost capitalism’s popularity.

Yet the left are pulling in the other direction. The election of Jeremy Corbyn, a self-described socialist, as leader of the Labour Party has prompted an outbreak of revolutionary enthusiasm among some of his devotees. John McDonnell, Mr Corbyn’s shadow Chancellor, once listed his interests as “generally fermenting the overthrow of capitalism”. He probably meant “fomenting” but the meaning was clear.

But what is this capitalism? What does the word stand for? It’s not a question that is asked enough. The journalist Paul Mason has published a book with the title “Post-capitalism” which, rather irritatingly, lacks any substantive discussion of what capitalism actually is.

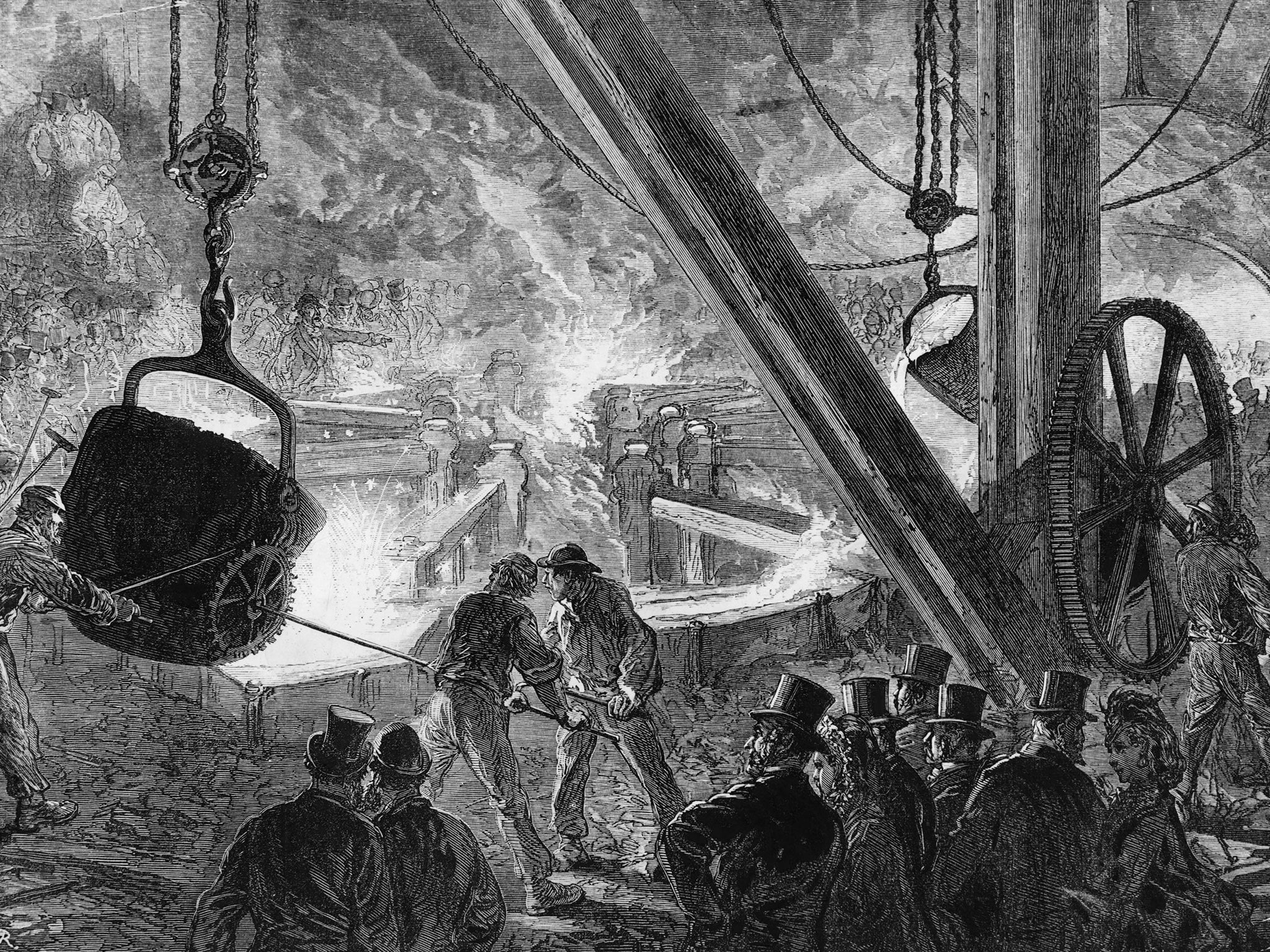

During the first phase of the industrial revolution, when people spoke of “capital” they were generally talking about physical assets such as textile factories, water mills, steel foundries and railway lines. The owners of these “means of production” were the capitalist class.

But the relative economic importance of physical assets has collapsed as the economies of the rich world have become more sophisticated. The bulk of the value of many modern businesses lies not in their physical assets but in their intangible capabilities. Apple is not the world’s most valuable company because it owns factories in China that make iPhones. Indeed, it subcontracts the production process to local firms. The value of Apple lies in the fact that it employs the creative talents who came up with the world-beating iPhone.

Thomas Piketty’s definition of “capital” in his 2013 magnum opus Capital in the 21st Century was not physical assets but financial wealth. These are very different concepts. Wealth includes non-productive assets such as housing. Indeed, Piketty’s own data makes it clear that the lion’s share of “capital” in many rich countries today is now made up of housing wealth.

But the old concepts are hard to shake. When pressed, people often still describe capitalism as a system under which the owners of financial capital (shareholders) offer up their resources to fund business ventures in exchange for a financial return (dividends paid by a company). Yet few large businesses need to raise money from investors in stock markets any longer. They can fund their expansions from internally generated profits. They are more likely to buy back shares with their free cash flow than issue new ones.

Ownership has changed too. Today many company employees are shareholders through their pension schemes. Does that give these workers economic power in the manner of the 19th-century capitalist class? Not really. Economic power usually lies not with shareholders but with the managers of companies, the executives. Sometimes it lies with the financiers who look after people’s investments, the professional asset managers employed by pension funds. But it is virtually never the ordinary shareholder who is in the driving seat.

There are common features to societies described as “capitalist”. They permit the (largely) free exchange of goods and services in markets. Private property rights are enforced by the law. But this is akin to saying that politicians all share the common features of a working mouth and an inflated sense of self-importance. It’s true but it’s not terribly informative.

There are a host of varieties of “capitalist” society. The capitalisms of the United States, the United Kingdom, Germany, France, Sweden, Japan and South Korea are all distinct. They all involve a greater or lesser role of the state in provision of services. They all have greater or lesser levels of state regulation of business. Some prescribe strict limits on the reach of markets. Others are more liberal. Some have large co-operative and not-for-profit sectors. They all do greater or lesser levels of fiscal redistribution and public investment.

It’s often said that “capitalism” has lifted billions out of poverty in Asia in recent decades. Yet it wasn’t the capitalism promoted by free-market fundamentalists that achieved this uplift in living standards. The histories of Japan, South Korea and Taiwan – and more recently China – reveal a dominant guiding role played by the state in their economic development. Far from focusing on their comparative advantages and flinging their gates open to trade, as fundamentalist theory dictates, the state deployed protectionism for “infant industries”. Trade was an important part of their growth stories, but like a powerful medicine it was taken in controlled doses.

Labels are often a substitute for thought, especially in politics where a naïve view holds sway that economic policies and institutions are either inherently “capitalist” or “socialist”. See “privatisation” and “the NHS” for two examples in the British context. Extremists of both the left and the right are attracted to this Manichean world where good and evil collide.

The irony is that it’s mainly rhetoric. It’s doubtful that Mr Corbyn and Mr McDonnell, whatever they call themselves, would seek to nationalise successful private firms if they won an election. Similarly it’s unlikely that Donald Trump, if he ever got his hands on the White House, would privatise popular socialised health programmes such as Medicare.

“Capitalism” doesn’t really exist. There are various modes of market-based economic, social and legal organisation in rich countries, some of which work well in some respects, and some of which don’t. There is a debate to be had about how to reform those modes to meet the often divergent needs and aspirations of different populations. But there is no magic “capitalist” or indeed “socialist” formula that all should follow. Such 19th-century labels are often an excuse to dodge the difficult job of figuring out what will work. If we must use labels it would be far better to talk of market economies and centrally-planned economies.

“Capitalism” as a concept has outlived its usefulness. It now merely spreads confusion and breeds dogmatism. In other words: a prime candidate for Confucian rectification.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments