Opinion polls, like democracy, are the worst option... apart from all the others

The pollsters failed in 2015, but they do know where they went wrong. Besides, they’re the only show in town

Your support helps us to tell the story

In my reporting on women's reproductive rights, I've witnessed the critical role that independent journalism plays in protecting freedoms and informing the public.

Your support allows us to keep these vital issues in the spotlight. Without your help, we wouldn't be able to fight for truth and justice.

Every contribution ensures that we can continue to report on the stories that impact lives

Kelly Rissman

US News Reporter

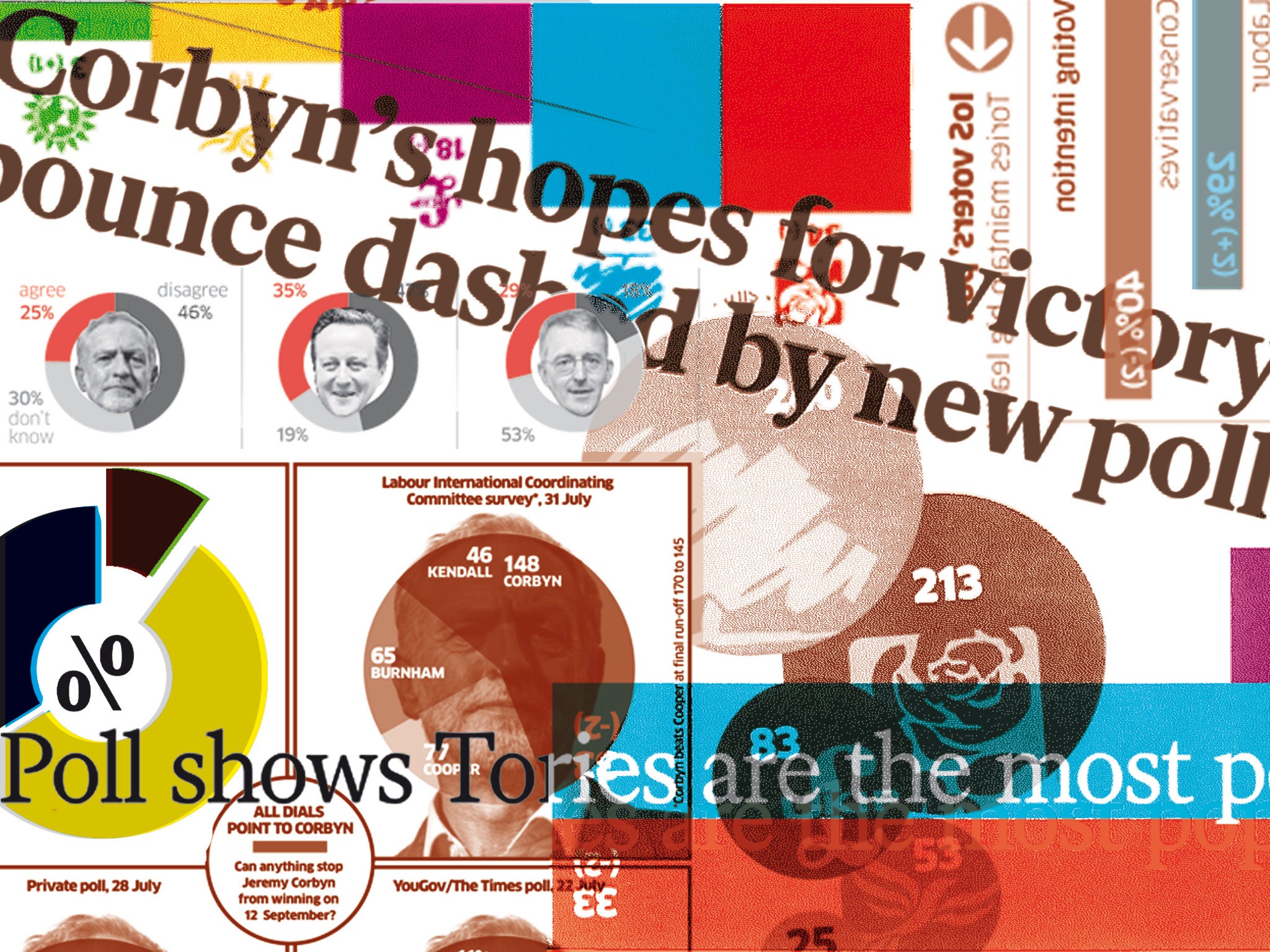

Why should I believe what a poll says ever again? It is one of those questions that guarantees applause on Question Time. It is normally asked, according to polls compiler Anthony Wells, by “a middle-aged man, who looks very pleased with himself afterwards and folds his arms with his hands sort of tucked in his armpits”.

The short answer is that they are better than any other way of trying to find out how people might vote. The alternatives are astrology, gut feeling or asking small groups of people who might give a clue as to how others think. This last is what journalists do when we report on by-elections: we stop people in the street, in pubs or at events. It doesn’t work very well, because it is not systematic enough. The more systematic it is, the more like an opinion poll it becomes.

Armpit-man is asking the wrong question, therefore. He should be asking why the pollsters got it wrong at the general election, what they have learned about their mistakes, and how confident we can be about their findings in future. Luckily, these are just the questions that were asked by the inquiry into the polls’ failure by Professor Patrick Sturgis that will be published in two weeks’ time for the British Polling Council. Three studies that have already been published tell us most of what I expect him to report.

First, there was the immediate response to the election by ComRes, The Independent on Sunday’s polling company. Its analysis suggested that different social groups predict their likelihood to vote differently. When, for example, people said they were “certain” to vote, ComRes found that the better-off were more likely to do so. The less affluent tend to exaggerate their likelihood to turn out to vote, appearing to boost Labour support. The company now has a “Voter Turnout Model” to adjust for this effect.

Second, Anthony Wells went through the polls produced by his company, YouGov, and identified problems with its samples. It seems that YouGov had too few over-75s in its quotas of old people, by focusing on simply getting the right number of over-65s, and too many politically engaged respondents in its quotas of young people. Together, these errors had the same effect as those by ComRes: overstating the Labour vote and understating the Conservative vote.

Finally, Matt Singh is the blogger who posted a celebrated analysis of opinion-poll data on the day before the election, suggesting that, if you looked beyond the simple “how do you intend to vote”, the Tories were going to win. He analysed the British Election Survey (BES), a series of academic polls carried out face to face, and identified the shifts that normal polls had missed.

Whereas normal polls suggested that people who voted Lib Dem in 2010 would strongly favour Labour in 2015, the BES found that the split between Labour and Conservatives was more even (26 per cent to 19 per cent). And whereas the polls at the time suggested that Ukip drew its support mostly from the Conservatives, the BES again showed a fairly even split: 19 per cent of the Ukip vote came from the Tories and 15 per cent from Labour.

Finally, while the polls at the time found few switching directly from Labour to the Tories, the BES suggested that a net 7 per cent of voters did so.

That, then, is much of what went wrong. Sample errors account for two- thirds to three-quarters of the difference between the final polls and the result. The rest of the gap may be down to politics. None of the inquests has found much evidence of late swing – of voters changing their minds at the last moment – but I suspect that doubt and uncertainty tended to be resolved in the Tories’ favour. The story of the election, paradoxically driven by inaccurate polls, was of a hung parliament in which Ed Miliband would be at the mercy of the Scottish National Party. That story was likely to push people one way. So were leadership poll ratings: Mike Smithson of the Political Betting website points out that the better-rated leader of the two main parties won in every election since 1979.

But what of the future? At the risk of sounding like armpit-man myself, haven’t the polls got it wrong before, been corrected and then got it wrong again? Indeed, they have. And, in the long run, the polls tend to be too pro-Labour. Of the past 13 elections, in only three have they been too pro-Tory. One of those was 2010 (even if only slightly). So why were the polls accurate six years ago and so far out last year? Again, I think, politics is part of the answer: Gordon Brown had earned grudging respect and voters were fearful of Tory spending cuts.

In future, we need to get better acquainted with probability – the polls are likely to be a bit out, so we need to judge in which direction the error is likely to be. We need to look beyond how people say they will vote to what they think of leaders and what things, such as the SNP, do they fear.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments