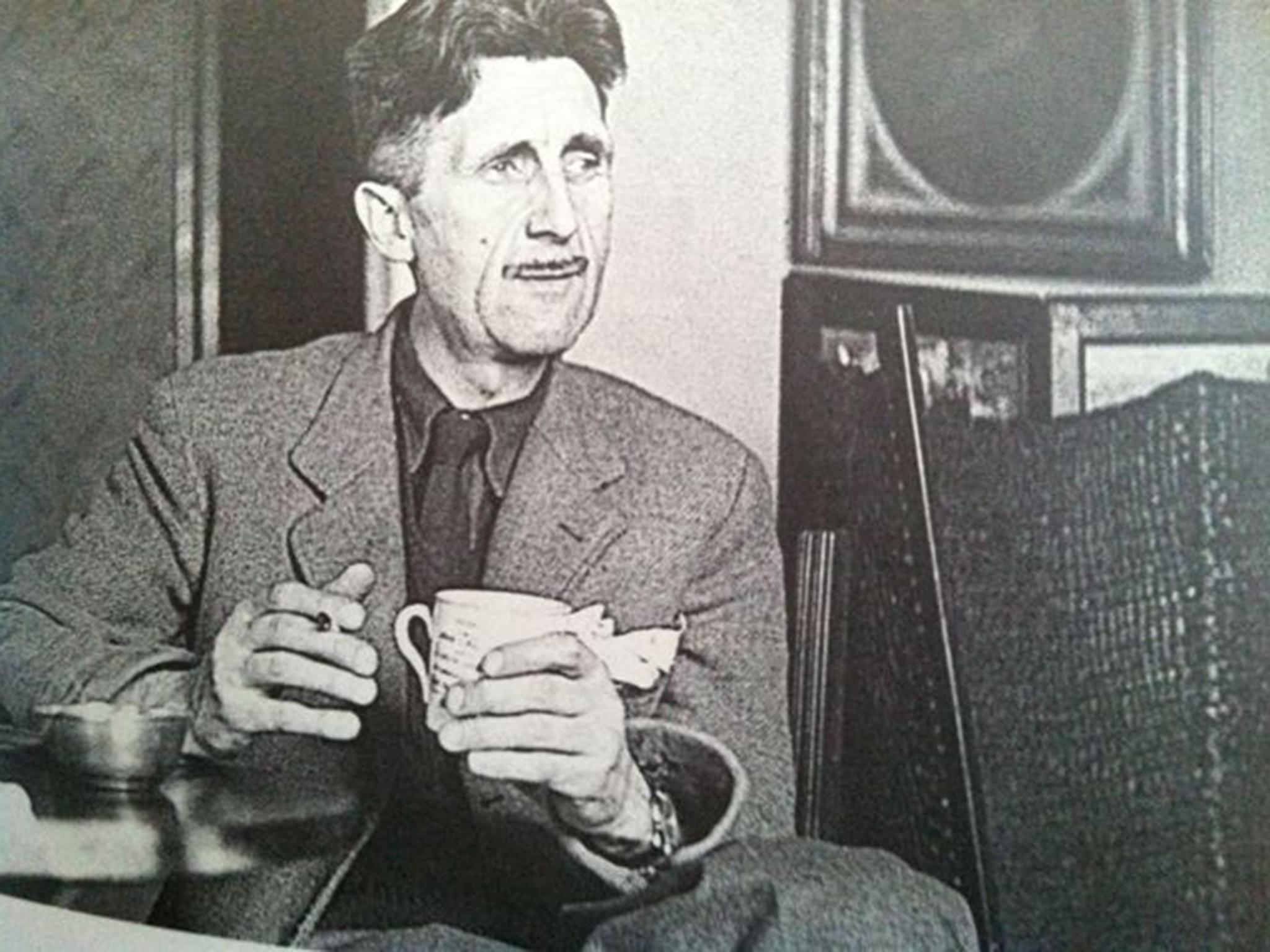

Nature Studies: In praise of George Orwell, unexpected lover of the common toad

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.As the weather this early January is so vile, I thought by way of consolation I would relay some views on the pleasure of the springtime to come, from an unfamiliar source: George Orwell.

We don’t normally think of the 20th-century’s premier political writer as a commentator on the natural world; our image of him is largely governed by Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty-Four. Yet since his childhood Orwell had a keen interest in nature which never left him, and towards the end of his relatively short life – he died in 1950 aged only 46 – he set down his views in an essay, which was really the literary genre he favoured most.

It’s called “Some Thoughts on the Common Toad”, and indeed, toads is what it’s all about, at least for the first 500 of its 1,600 words. A keen and close observer of natural phenomena, Orwell saw the toad emerging from underground hibernation as a notable sign of spring, just as much as the appearance of the daffodil or the swallow, but one not nearly so appreciated in literature or popular culture; and with his natural sympathy for the underdog and the unregarded, he wanted to pay Bufo bufo its due (it had never had “much of a boost from poets”, he laments).

He celebrates it with an amusing, light touch, describing in detail toad mating habits, which as we know resemble sumo wrestling, and pointing out that toad eyes are a beautiful golden colour; but his theme widens out to a celebration of the springtime in general, and then it suddenly deepens with a question that comes as a sharp shock: “Is it wicked to take a pleasure in spring and other seasonal changes?”

Wicked? What on earth does he mean by wicked?

You realise as you read on that he means just what he says. Not a few people on the left have accused him, as a socialist writer, of taking a politically reprehensible position in pointing out that life is frequently made more worth living by things such as a blackbird’s song, while “we all ought to be groaning under the shackles of the capitalist system”. A favourable reference to nature in one of his articles is likely to bring him abusive letters, he says.

Hard to believe? Well, this is the traditional indifference of the left to the natural world, which becomes more hostile the further left you go, until with Mao Zedong in China you reach an enmity which verges on the crazy (admirably documented in Judith Shapiro’s gripping 2001 book Mao’s War Against Nature). This hostility may not be as strong today as it was when Orwell wrote his essay, in 1946, but it still seems to occupy a stubborn corner of the socialist soul: love of nature is seen merely as a bourgeois pastime which has no bearing on the struggle for social justice, and so is worthless.

Orwell, as a socialist, rejects this notion out of hand, which is why “Some Thoughts on the Common Toad” is memorable. “I think that by retaining one’s childhood love of such things as trees, fishes, butterflies and – to return to my first instance – toads, one makes a peaceful and decent future a little more probable,” he writes.

He makes the point decades before the modern environmental movement arose, and it clearly stems from the characteristics for which we cherish him: his common humanity, his common decency, and his common sense. For after all, as he points out – which may be something to dream about in this sodden January – the pleasures of spring are available to everybody, and cost nothing.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments