After my nan died, I learnt to confront death in the best possible way

When people we love die, they don’t want us to crumble. We’re stuck with muddling on somehow, as impossible as it feels

We live, others die, and at some point afterwards, life must go on. Death’s so normal and banal, yet ring-fenced, like a shameful secret. It’s considered morbid and depressing, but only because it’s unknown. No one knows what to say, so we don’t.

We buried my nan on New Year’s Eve. It was shocking to watch her body go down a hole, even though it shouldn’t have been. We’d spent over a week in hospital with her, waiting for this moment. Numbness had set in, and I thought I’d already pre-grieved, because there is nothing to fill your days with than preparing yourself for the finish line. She was frail in the end, but my memories of her are rooted in the past. She was such a formidable woman. I thought she’d outlive us all.

She wasn’t life-threateningly sick for long, but she needed constant care due to a long physical decline. I thought it fair enough that she might be fed up, but she never said she was. She didn’t speak much at the end, but there was joy there and smiles.

Two weeks before she died, the last time I saw her well, we were laughing as I struggled to slide her back into bed: she was too heavy to drag higher onto the pillows. We got there in the end, but I did think then that this wasn’t a great life for her. Not for someone who had been so active.

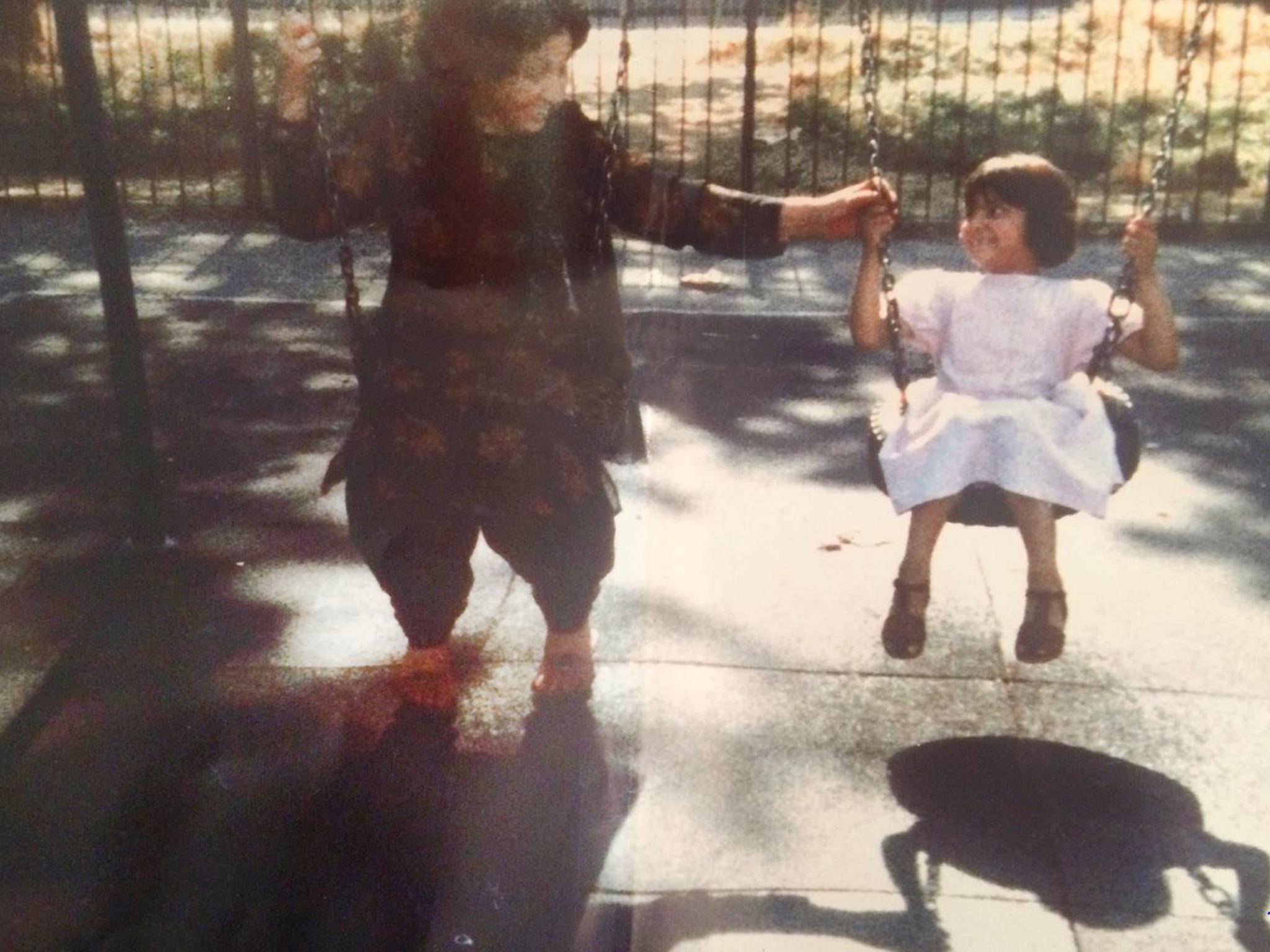

Strong men don’t feature heavily in my formative years. I come from a matriarchal lineage, and my nan was at the helm. I called her “Biggie”, after she named herself “Big Mum”, because she was too young to be a grandma when I was born. When my mum was at work, Biggie filled in the blanks of my care. She always had a hundred things to do and was permanently on her way somewhere – running errands, taking English lessons, or fitness classes – but she’d pick me up from school and off we went. When I was older I plaited her hair, lit her cigarettes, chattering away and getting her to tell me – again – about living in Lahore after she was married, which she said was the happiest time of her life. Those conversations stopped a long time ago.

No one knows her real birthday, but the hospital wrist-band said March 8, 1938. That’s what went on the immigration papers. Entirely accidental, but I love the fact that it’s the date for International Women’s Day. She was widowed at 35 with six children, aged 16 to three, in London, which was still a foreign city to her. Then 15 years later, her daughter was killed in a car crash. That’s too much trauma for one life. She never recovered. How can you?

An ambulance took my nan to hospital four days before Christmas. Plans ground to a halt and everyone she’d loved gathered there as news spread she was unlikely to return home. All day we would sit, awaiting the inevitable. We set her up with headphones and a man with a beautiful voice reciting the Quran in her right ear without knowing for sure if she could hear. Prayers were performed and everyone said what they needed to. I whispered that I loved her on a few occasions and left it there. It was an uncomplicated relationship with no history to repair.

It’s inconsolable watching someone you love wilt and change colour while trying to keep it together. You hold onto doctors who say: “She’s not in any pain,” and make do with that. I read about “signs to look for” in end-of life-articles obsessively, sharing them on our WhatsApp group while everyone was in the same room. Each night we’d compare notes, but conclusions were the same: it could be hours, days. It will happen. I didn’t know if I wanted to be in the room when it did.

After a week of flat whites and M&S sandwiches, sometime after Boxing Day, I was wishing she’d hurry up so I could crack on with facing life without her. “I’m off for a walk” became another way of saying: “I’ll be in the car park passive smoking, cos I could really do with a rollie and drink right now but what a bummer it is I’ve stopped doing both”.

Her death took 10 days and we’ll never know why. The privilege of understanding the vacuum that exists between being and not being belongs solely to those who experience it. No medic or spiritual leader can offer definite answers. As her body shut down, her heart continued to beat strongly. She opened her eyes sometimes, moved a bit, then for the rest of those days it was just her breath rising and falling. The best advice I got was to “be really present”.

I held her hand a lot and I was holding it at the end. There’s nothing more raw or that makes you sharply aware of being alive, than staring death in the face. When you see life slip through a side door it forces you to question the attachments we make.

It sounds dramatic because it is. It creates an existential crisis, and you realise that things will never be the same. You won’t be the person you once were - you don’t want to be. That’s the permanent and final thing about death. It puts a wonky spin on everything, forces you to work out who you are again.

Grief is a relentless beast that refuses to leave you alone. It makes you foggy-headed with a perpetual feeling of ‘what’s-the-point’, so that when in an attempt at #selfcare, you walk to the park, only to be hit on the way by a wave of despair that makes even buying a coffee a chore.

When people close to me die, I read W H Auden’s Funeral Blues. I wallow in his description of the unparalleled, lonely pain that is grief, because I don’t want to talk to anyone and I don’t know what to say. I rarely make it to the last line of the poem without crying, but when I read it while holding my nan’s hand, just hours before her heart stopped beating and mine was hurting, I thought how kind it was of her to take her time before leaving us. When my grandad died, no one got to say goodbye.

The poem closes with: "Pour away the ocean and sweep up the wood / For nothing now can come to any good."

But when people we love die, they don’t want us to crumble. We’re stuck with muddling on somehow, as impossible as it feels. And my sense with Biggie is that she probably stayed with us as long as she did to give us time to come to terms with her passing, until she was sure we would "come good".

Twitter: @nadiagilani

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies