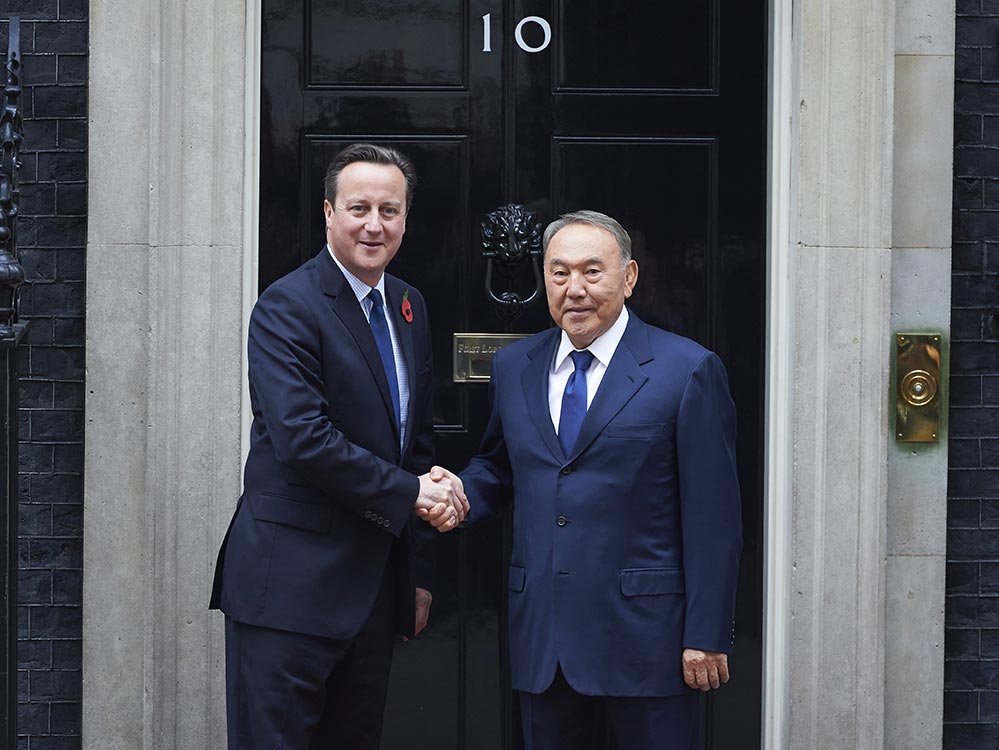

Kazakhstan, Russia and two very different approaches to crisis management

Having prioritised economics over politics, Kazakhstan is well placed to weather the financial difficulties currently afflicting the Eurasia region

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.From the publication of the Panama Papers to the collapse of the Doha oil negotiations, recent news has not shown the political elites of post-Soviet countries in a positive light. Russia, Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan – nations that relied on natural resources for several decades – are now looking vulnerable thanks to a lack of transparency in their economies and a worsening of financial conditions. In 2016, Russia’s economy will contract by 1.9 per cent, according to the World Bank, while Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan’s will barely grow (by 0.1 and 0.8 per cent). Budget deficits are on the rise. Local currencies fall as citizens prepare for a prolonged depression.

What’s interesting is the different ways in which elites, at least in Russia and Kazakhstan, have reacted to the crisis. In Russia, the government seems not to care about the national economy at all. The so-called “anti-crisis program”, comprised of several random measures, is valued at a feeble 0.2 per cent of GDP. At the same time, the government raised military outlays to 19.8 per cent of overall budget spending while the Interior Ministry got another 8.2 per cent (both figures are at post-Soviet highs). Moreover, Mr Putin announced the creation of a new paramilitary service, the National Guard, directly answerable to the President. Fearing unrest, the government is putting in place measures to shut down a protest movement should one arise.

Secondly, Russia continues to reinforce the state’s grip over the economy, extending its countersanctions, and questioning foreigners’ participation in a new wave of privatisation deals planned for this year. Russia’s imports are falling dramatically, decreasing from $27.4bn in June 2014 to $9.7bn in January 2016. The government, it seems, is preparing for a long defence “against the whole world”, economically as well as militarily. Only tax rises can fund this struggle.

Thirdly, and perhaps most importantly, Russia’s financial elite is now primarily concerned not with supporting business, but by joining the political class. It’s no wonder, given the main means of personal enrichment is now state contracts and purchases. In 2015, more than 70 per cent of budget-financed infrastructural deals were granted to just three companies. More and more officials are accused of corruption and dismissed, some of them fleeing Russia only to be extradited later, like the former chief of the State Border Control service Dmitriy Bezdelov. Plundering the state budget and the country’s wealth remains the main source of the Russian political elite’s private enrichment.

If, however, one looks at other post-Soviet states, considered by some to be equally corrupt and badly managed, a better approach seems to be taking hold. For example Kazakhstan – not a country renowned for human rights – has started to prioritise economics over politics. The budget now devotes more than 55 per cent of outlays to the development of the national economy, up from 39 per cent last year.

The anti-crisis action plan is set to receive over twice the amount of state funding as the military, which was cut by 17 per cent in 2015. In 2016, one per cent of GDP (4.8 per cent of the budget spending) will go to the military, 4.2 times lower than in Russia. After the 2009 crisis, the Kazakh economy grew 1.2 per cent while Russia’s dipped by 7.9 per cent. Then, Kazakhstan responded to the crisis by attracting foreign capital with new projects focused on interstate cooperation. There was the modernisation of the port of Aktau on the Caspian shore, a huge infrastructure project, with new highways connecting the port to the Chinese border.

The main Kazakh oil projects – giant Tengiz and Kashagan fields – were developed by European, U.S. and Japanese companies (with combined investments valued at $65bn). Chinese investment is also growing, already exceeding the country’s investments in Russia and outstripping Russian-owned assets in Kazakhstan by 11 times. Overall tax revenues in Kazakhstan (as a proportion of GDP) are 1.6 times lower than in Russia, and there is no intention to push them up due to the current crisis conditions.

Meanwhile a new, interesting trend is emerging. Increasingly, senior Kazakh officials are quitting positions in government to start their own businesses, aiming not to pillage the state’s finances but to encourage foreign investment in the country. Bulat Utemuratov, a senior official in the president’s administration, recently launched a joint venture for investing in Kazakh banking and telecom sectors. Another former bureaucrat, former Secretary General of the ruling Nur Otan party, Kairat Satybaldy, left government to become chairman of Alatau Capital Invest, which teamed up with Baring Vostok to put money into several projects in the banking sector. The company also cooperated with China National Machinery, which has invested $200m in developing an automobile production facility in Kazakhstan. Satybaldy, together with other former government officials, is also engaged in establishing a global financial centre in Astana.

The paths of post-Soviet states, it seems, are diverging. The main reason for this is the countries’ is history, and geopolitical clout. While Russia used its moment to secure its dominant position in Eurasia, neglecting its economic needs, Kazakhstan embarked on a more realistic course trying to integrate itself into the regional economy and even sacrificing some of its elite’s interests for the sake of nation’s “peaceful rise”. They will reap the rewards.

Vladislav INOZEMTSEV, Ph.D. (Econ.) is Senior Fellow with the Atlantic Council in Washington (DC) and Professor at the Higher School of Economics in Moscow

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments