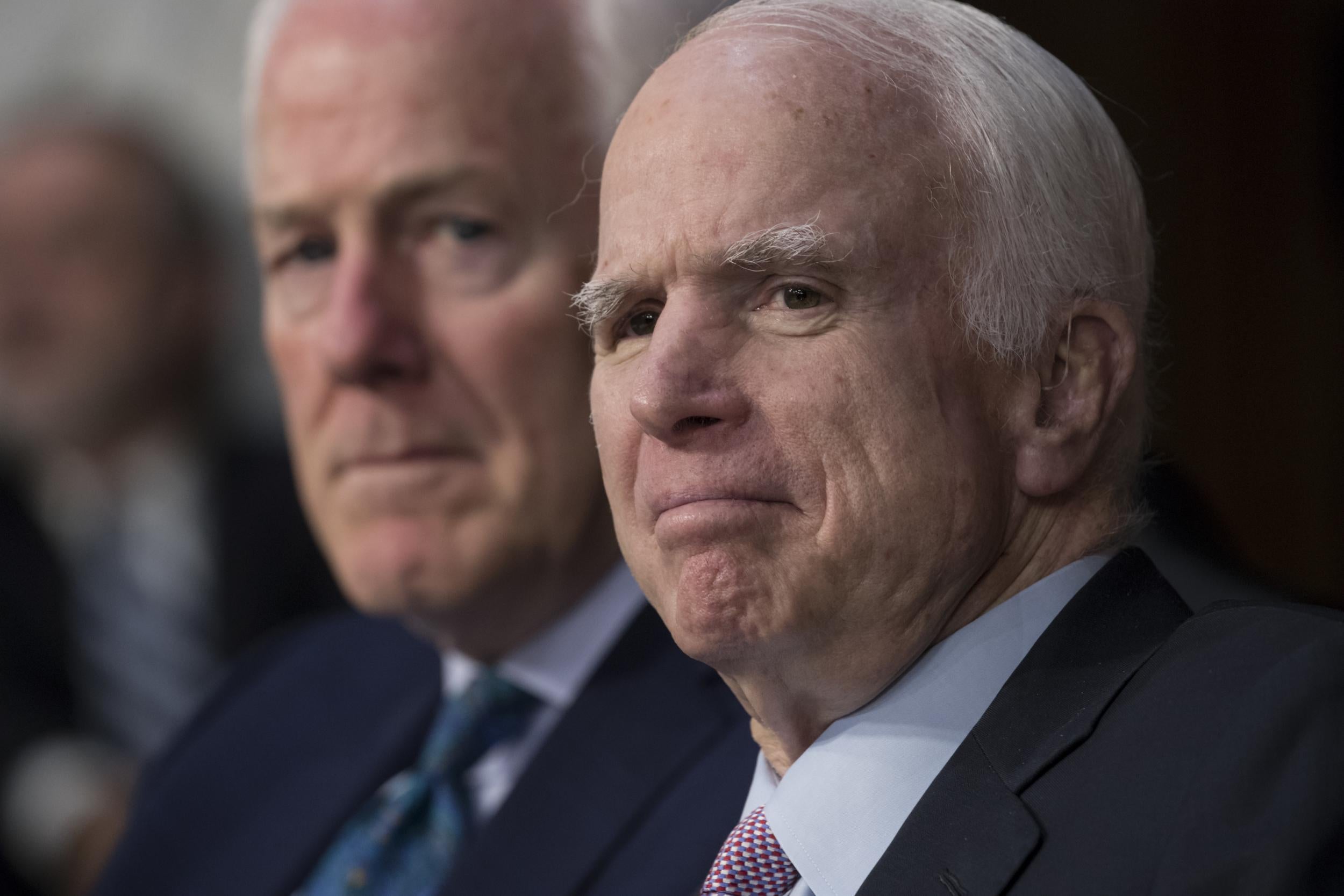

Obama's tweet to John McCain about his diagnosis was the last thing cancer survivors wanted to see

Our unthinking characterisation of cancer as a 'battle' hands responsibility for recovery to the patient – and creates the notion that only the ‘strong’ or ‘deserving’ survive

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Glancing through Twitter this morning, I noticed a friend of a friend responding to Barack Obama’s tweet in support of Senator John McCain who has been diagnosed with brain cancer: “John McCain is an American hero & one of the bravest fighters I've ever known. Cancer doesn‘t know what it's up against. Give it hell, John.”

As sad as this news is, and as much as I laud Obama’s sentiments, I have to take issue with his use of war metaphor to frame a response to his colleague’s illness. For starters, talk of cancer as a “fight” is nearly always used to reassure the speaker rather than addressing the emotional and physical reality of the person who is ill. Without wishing to overstate it, the tweet has a lofty, imperious tone to it, as though spoken by someone who is used to getting their own way. Even after successful treatment, if cancer teaches you anything, it is that this rarely happens. Our will to “fight” the disease is irrelevant to whether or how we get better.

Martial metaphors of cancer are lacking for several other reasons. After major surgery, weeks of radiotherapy, or even a single day on a chemotherapy ward, it is possible to feel that the so-called “battle” is being done to you, not that you are some brave warrior choosing to repel the evil forces of the disease inside your body.

The advances of medical science are a wonderful thing, but that does not change the fact that many treatments for cancer, sometimes involving all of the above treatments combined, can be brutal. If I were diagnosed with a relapse tomorrow I would ask for the same treatment again, but a decision to “fight” would not come into it.

Thirdly, and most insidiously, our unthinking characterisation of cancer as a “battle” hands responsibility for recovery to the patient. As we have seen, when you are at your lowest ebb, this is a laughable proposition. Further, it creates the notion that only “strong” or “deserving” patients survive cancer, the corollary of which is that those whose treatment is unsuccessful are weak or deficient in willpower. This is dangerous. We don’t talk about “fighting” a hip replacement, or diabetes. Why should we when it comes to cancer?

Finally, the idea of cancer as a “battle” sentimentalises the disease, when there is absolutely nothing romantic about it. Think back to any number of disclosures of celebrities “fighting” or, sadly, dying from cancer. If their treatment is ongoing, they are called “brave”, as in “Brave X’s new cancer haircut”, as though losing one’s hair were a fashion choice. The story is greeted with exactly the same word even when the news is less positive: “Brave X loses year-long cancer battle”. Again, this says more about us as onlookers than the individual concerned. It is as though we need the comfort of persuading ourselves that the deceased has “given it everything”, or was ‘plucky” to the end.

My friend of a friend on Twitter was commendably direct in her reply to the former US President: “Urge us to be courageous; tell us you'll support us; acknowledge that it's shit & you don't know what to do. Just don't tell us to fight.” Unfortunately this kind of clarity is sadly lacking in much of our culture’s discourse around cancer. Consider Cancer Research UK’s Race for Life TV ad (2013), which includes the immortally dreadful line “Cancer, you prat.” The seriousness of the delivery, let alone the subject matter, almost dares you not to laugh. Surely we can do better.

I have no doubt that Obama meant well with his tweet. With its overtones of taking control and a positive mindset, it is the kind of statement our culture responds well to. It may even have been a comfort to John McCain and his family. But none of this stops it being misplaced, or founded on a myth that only those who “fight” cancer survive it.

Whatever our relationship to cancer, whether we are a researcher, doctor, patient, or family member, refusing to use war metaphors to describe our experience of it would be a better way to honour those we support and love.

Anthony Wilson is a poet, writing tutor, blogger and Senior Lecturer at the Graduate School of Education, University of Exeter. His most recent books are Lifesaving Poems (Bloodaxe, 2015), Riddance (Worple Press, 2012) and Love for Now (Impress Books, 2012), a memoir of cancer. You can visit his website: www.anthonywilsonpoetry.com or Twitter: @awilsonpoet

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments