America’s true special relationship isn’t with the UK

While we often talk about the ‘Special Relationship’ between the US and the UK, that relationship exists mostly at the government level. In the hearts and minds of the American people, however, the true special relationship is with Ireland

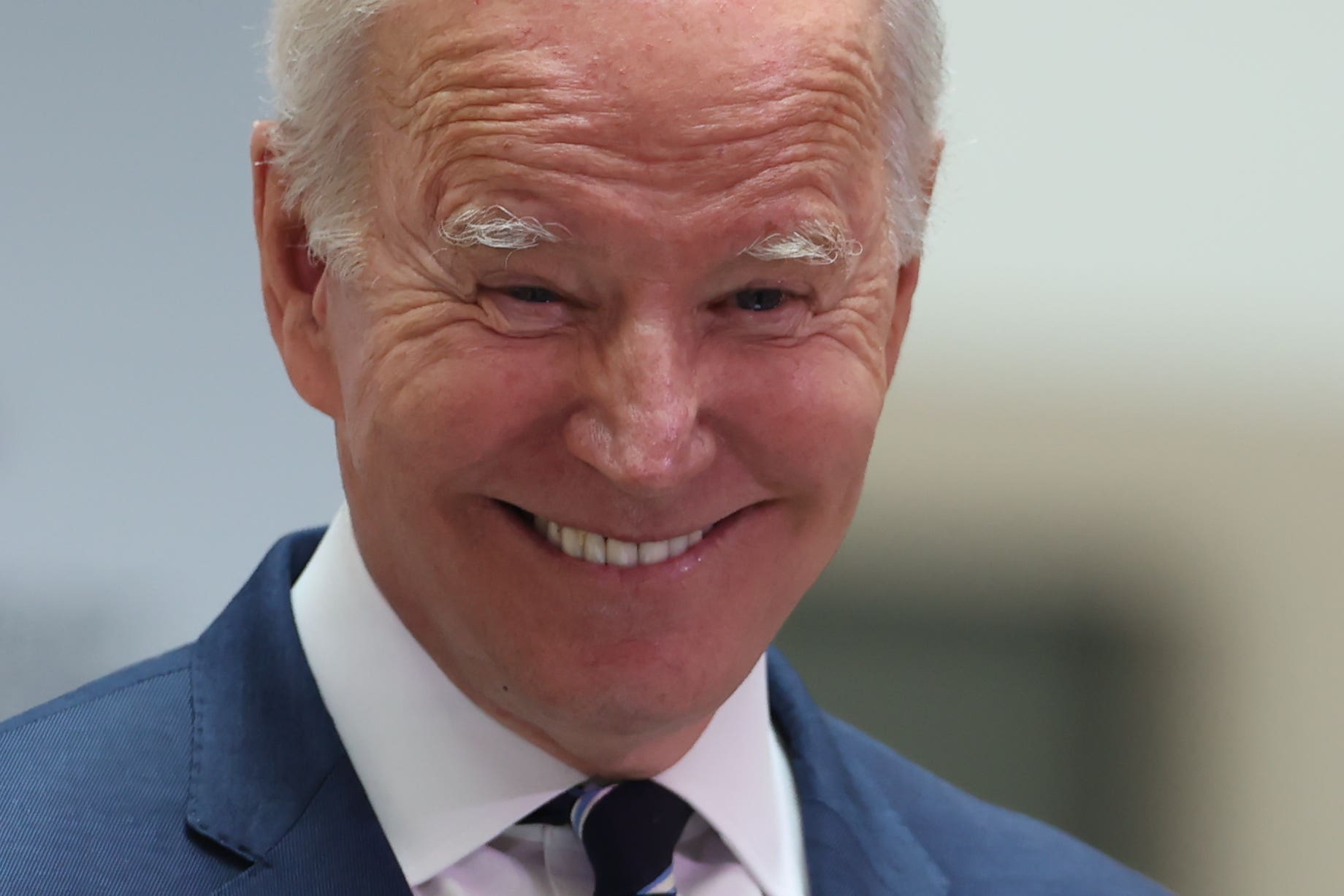

There is nowhere in the world Joe Biden should be today but Belfast.

A proud descendant of Irish immigrants, the President of the United States of America is today in Northern Ireland commemorating the 25th anniversary of the Good Friday Agreement. It makes sense; the Americans were intrinsically involved in negotiating the deal which ended three decades of sectarian violence between the Protestant Unionists and Catholic Nationalists. The Good Friday Agreement stands as a triumph of American diplomacy and a global blueprint for ending civil conflict.

As this timeline of American involvement in the peace process shows, the United States was able to play such an important role in negotiating the Good Friday Agreement because of its unique history. Many of the key instigators of American involvement in Northern Ireland were Irish Americans themselves, from House Speaker Tip O’Neill in the 1980s to President Bill Clinton in the 1990s, who famously granted a 48-hour visa to Sinn Fein leader Gerry Adams – a watershed moment that kickstarted the peace process.

This should be no surprise. While we often talk about the “Special Relationship” between the US and the UK, that relationship exists mostly at the government level. In the hearts and minds of the American people, however, the true special relationship is with Ireland.

To understand why, one must understand American demographics and American history. A nation which broke from Britain in the 18th century only to become its staunchest ally in the 20th, we are also a nation in which 31.5 million citizens claim Irish ancestry. That is a population nearly seven times that of Ireland itself, accounting for one in ten Americans, living in every county of the United States.

Beyond that, though, exists a kinship that many Americans feel with the Republic by dint of our parallel histories. Both Ireland and the United States are erstwhile colonies of the United Kingdom. As I have previously written, we have Lexington and Concord; the Irish have the Easter Rising. We have our Revolutionary War; Ireland has its War for Independence. We have George Washington; the Irish have Michael Collins.

In the 19th century, immigration to America from what is today the Republic of Ireland proliferated – thanks in large part to the oppressive laws instituted by the British and, of course, the Potato Famine. Sadly, the Irish did not find a warm welcome in the United States, though. For example, in an 1855 incident that would become known as “Bloody Monday,” at least 22 – though some Irish Catholics estimated the number was more than 100 – Irish were massacred in Louisville, Kentucky.

This stigmatization meant that the Irish and their descendants were not assimilated into mainstream American culture (that is, White Anglo-Saxon Protestant, or WASP, culture) as quickly as immigrants from England, and even Scotland and Wales, were. Whereas the “Scots-Irish” – that is, descendants of Ulster Scots who emigrated to North America in the 17th and 18th centuries – were thoroughly Americanized by the time of the Civil War, the more recent Catholic Irish immigrants from the south were marginalized in ways that kept them insular and therefore promoted cultural retention.

Over time, though, the Irish began to be more accepted into polite society, particularly as “lace curtain Irish” began to attain a level of economic affluence and respectability as opposed to the “shanty Irish” who were stereotyped as lazy, drunk, and violent. As they began to exert more influence over American life – including American politics through political machines in cities like New York, Boston, and Chicago – their culture began to become ingrained in American culture, to the point where even Americans who were not of Irish descent proudly participated in Irish traditions.

Most Americans will know at least the opening lines of “Danny Boy,” not even realizing that it was written by an Englishman. In the 1970s and 1980s, the soap opera Ryan’s Hope focused on the trials and tribulations of the Irish-American working class in New York City, while more recent shows like Roseanne and its sequel, The Conners have centered around an Irish-American working-class family. Not coincidentally, one of the stars of the latter also starred in the American version of Shameless, which centered around an impoverished Irish-American family on the South Side of Chicago – a city that dyes its river green every St. Patrick’s Day. (Indeed, most traditions related to St. Patrick’s Day originated in America!)

These Irish Americans form the backbone of the white working class, and they vote in numbers that make them a bloc neither party can ignore. There is a reason politicians and presidents of both parties have felt a vested interest in not only courting Irish voters but also promoting peace in Northern Ireland.

The affinity the American people feel towards the Republic transcends party lines. It is a kinship forged by shared blood but also shared struggles for independence and self-determination against the British. Some even see the British as an occupying force; one friend’s mother has a bumper sticker on her car that reads “26 + 6 = 1,” a not-so-subtle indication that she supports the six counties of Northern Ireland uniting with the 26 counties of the Republic.

This is all worth remembering as President Biden visits Belfast today. “We can’t allow the Good Friday Agreement that brought peace to Northern Ireland to become a casualty of Brexit,” Biden tweeted in 2020. “Any trade deal between the U.S. and U.K. must be contingent upon respect for the Agreement and preventing the return of a hard border. Period.”

Biden’s visit today underscores that warning to Westminster, as the Conservative Party has not given up hopes that a post-Brexit trade deal might be reached. Ensuring the continual free flow of goods and people across the border is essential from the American perspective, not just because the US rightly sees the Good Friday Agreement as a triumph of American diplomacy, but because so much of the United States is skeptical, at best, of British involvement on the island of Ireland.

For its part, the United States must continue to strike the right balance. The Northern Ireland Protocol agreed upon by the British government and the European Union ensures there will be no hard border between the Republic and the province. However, the Democratic Unionist Party has been reluctant to adopt the Windsor Framework which would create two lanes of traffic for goods heading from Great Britain to Northern Ireland, fearing that it cuts off the province from the rest of the United Kingdom.

The DUP pulled out of the power-sharing agreement in 2021, collapsing the Northern Irish executive. President Biden has called for a return to the power-sharing agreement at Stormont, but his words are less likely to be heeded by the DUP, as many of its members view him skeptically and as favoring Dublin and Brussels. This could show the limits of American influence in Northern Ireland.

Alternatively, it could be the chance for a reminder that America and the Ulster-Scots share a kinship as well. There is a statue in Larne commemorating the voyage of the Friends’ Goodwill, which carried 52 passengers – most of them Ulster Scots – to Boston, beginning a migration of some 300,000 Ulster Scots to the New World in the 18th century. The descendants of these early emigrants today populate every state but are especially found in and around the Appalachian Mountains.

These ties are already being explored and strengthened through organizations such as the Ulster-American Heritage Symposium and the Mellon Centre for Migration Studies. We should, if the parties in Northern Ireland ask us, consider using these ties to help bring about an agreement on the post-Brexit settlement.

The Good Friday Agreement, after all, stands as one of the United States’ greatest diplomatic achievements. It was negotiated in large part because of our shared kinship with the nationalists. Today our kinship with the unionists could allow us to play a similar role in the mediation of the post-Brexit crisis.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies