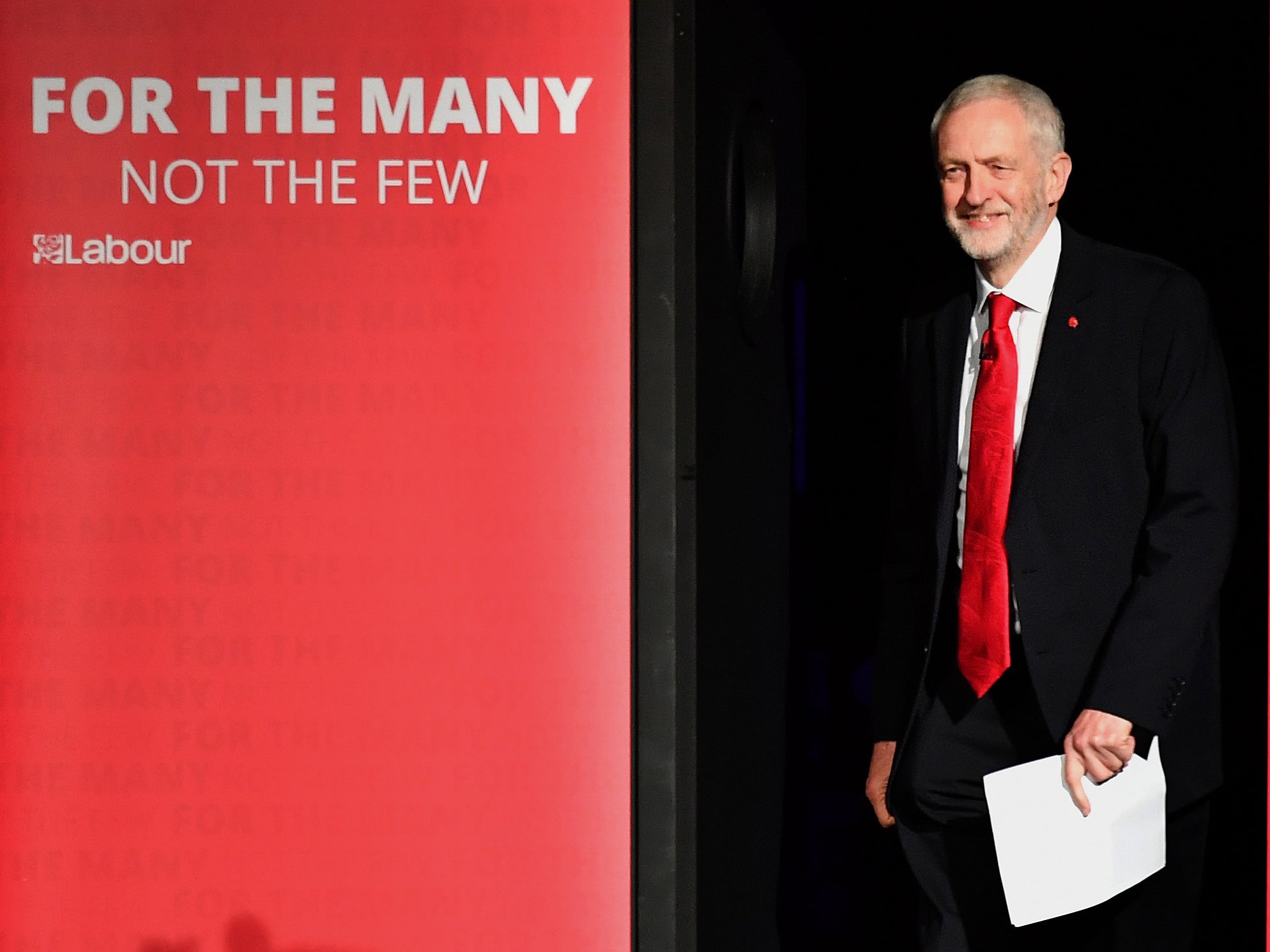

Jeremy Corbyn and Momentum are tightening their grip on Labour – but for how long?

The weakness of Corbynism is that it will last only as long as he does. It depends for its unity and survival on him personally

Your support helps us to tell the story

This election is still a dead heat, according to most polls. In a fight with such wafer-thin margins, we need reporters on the ground talking to the people Trump and Harris are courting. Your support allows us to keep sending journalists to the story.

The Independent is trusted by 27 million Americans from across the entire political spectrum every month. Unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock you out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. But quality journalism must still be paid for.

Help us keep bring these critical stories to light. Your support makes all the difference.

Eddie Izzard versus Jon Lansman. The comedian versus Tony Benn’s organiser: the struggle for socialism takes curious forms. The ballot papers to elect three extra members of Labour’s National Executive went out this week.

Lansman and his fellow members of the Momentum slate are almost certain to win. Most Labour Party members are enthusiastic supporters of Jeremy Corbyn and will vote for the candidates recommended by Momentum, the organisation founded by Lansman to carry on the work of the Corbyn leadership campaign.

Izzard, running on a pro-Europe platform, will probably come a creditable fourth. When the results are announced in mid-January, Corbyn will have tightened his grip on Labour’s ruling body.

For the first two years of his leadership, the party leader could not rely on it to back him: its 35 members were split down the middle between supporters and sceptics. Now, the National Executive is firmly in Corbynite hands.

Kezia Dugdale, the non-Corbynite leader of the Scottish Labour Party, has been replaced by Richard Leonard. Glenis Willmott, the non-Corbynite Labour MEP, stood down as chair of the National Executive in October and was replaced by Andy Kerr of the Communication Workers Union. The non-Corbynite shopworkers’ union Usdaw took the extra trade union seat, but the three new seats for party members’ reps and a rule change to ensure a Corbynite Young Labour representative mean that Corbyn will have a secure majority in the three bodies that control the national party: the National Executive, the party conference and the shadow cabinet.

Last year, I looked at the many battlegrounds of Labour’s civil war. Of these, the non-Corbyn forces still control the deputy leadership, the parliamentary party and local government. Each of these is under siege, but they can hold out for years.

Tom Watson as deputy leader has his own mandate from party members. He may be joined by a second deputy leader when Corbyn’s review of party organisation reports to next year’s annual conference, but he is unlikely to be challenged: that would still require 57 Labour MPs or MEPs to nominate a candidate against him.

Labour MPs remain overwhelmingly unconvinced by their leader. Most of them remain in a state of limbo between resistance and acceptance. It seemed unsustainable and yet the party was able to fight a general election and deprive the Conservatives of their majority in this peculiar state. And it is likely to continue. Deselecting MPs is hard. If they are popular in their area there is a risk they could stand down and fight a by-election. So I doubt if Momentum will try to replace more than a handful of MPs at the next general election.

Finally, local government remains the power base of non-Corbyn Labour. Sadiq Khan and Andy Burnham control big budgets and can make a difference to voters in London and Manchester. The council leaders of Derby and Preston, and Steve Rotheram, the mayor of the Liverpool City Region, are the only leaders who are Corbyn supporters. That is why the north London borough of Haringey is in the news: Momentum has exploited an unpopular housing regeneration project to deselect councillors and to ensure a pro-Corbyn majority after next year’s local elections.

The Corbyn revolution, therefore, is dangerously incomplete. Even with a firm grip on the National Executive and strong support from the party’s 550,000 members, Corbyn cannot impose his will on MPs and Labour local government. The weakness of Corbynism is that it will last only as long as he does. It depends for its unity and survival on him personally.

His supporters even rewrote the party rules at the annual conference in Brighton to make it easier for a “core group” supporter to stand for the leadership when Corbyn goes. But who would that be? Even if John McDonnell or Rebecca Long-Bailey stood, I don’t think they would win. Emily Thornberry and Angela Rayner would both stand a better chance, and neither of them is a pure Corbynite. They were both listed as “core group plus” in the list leaked last year from someone close to Corbyn’s office.

This, I think, is the key to understanding the future of the Labour Party (although, given that I thought Corbyn would come fourth in his first leadership election, treat it with caution). Most of the party members love Corbyn, but, as Luke Akehurst argued this week, they are not wedded to his ideology. They want someone they see as left-wing, with charisma and an eagerness to bash the Tories.

Despite Brexit, the next election is still likely to be in 2022. By then Corbyn will be 72. He intends to fight it, and he could win it, but it is four and a half years away. And as soon as he has gone, Corbynism will mutate into something else.

Update Monday: I have corrected the extra trade union seat on the National Executive. It went to a non-Corbynite. And I have added the council leaderships in Derby and Preston to Steve Rotheram in Liverpool as the only Corbyn-supporting local government leaders.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments