Isis profits from destruction of antiquities by selling relics to dealers – and then blowing up the buildings they come from to conceal the evidence of looting

A Lebanese-French archaeologist tells Robert Fisk about her unique answer to a unique crime

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.So why is Isis blowing to pieces the greatest artefacts of ancient history in Syria and Iraq? The archeologist Joanne Farchakh has a unique answer to a unique crime. First, Isis sells the statues, stone faces and frescoes that international dealers demand. It takes the money, hands over the relics – and blows up the temples and buildings they come from to conceal the evidence of what has been looted.

“Antiquities from Palmyra are already on sale in London,” the Lebanese-French archaeologist Ms Farchakh says. “There are Syrian and Iraqi objects taken by Isis that are already in Europe. They are no longer still in Turkey where they first went – they left Turkey long ago. This destruction hides the income of Daesh [Isis] and it is selling these things before it is destroying the temples that housed them.

“It has something priceless to sell and then afterwards it destroys the site and the destruction is meant to hide the level of theft. It destroys the evidence. So no one knows what was taken beforehand – nor what was destroyed.”

Ms Farchakh has worked for years among the ancient cities of the Middle East, examining the looted sites of Samarra in Iraq – where “civilisation” supposedly began – after the 2003 US invasion. She has catalogued the vast destruction of the souks and mosques of the Syrian cities of Aleppo and Homs since 2011.

Indeed, this diminutive woman, whose study of the world’s lost antiquities sometimes amounts to an obsession, now describes her job as “a student of the destruction of archeology in war”. Over the past 14 years, she has seen more than enough archeological desecration to fuel her passion for such a depressing career. Politically, Ms Farchakh identifies a particularly clever strain in Isis.

“It has been learning from its mistakes,” she says. “When it started on its archeological destruction in Iraq and Syria, it started with hammers, big machines, destroying everything quickly on film. All the people it was using to do this were dressed as if they were in the time of the Prophet. It blew Nimrud up in one day. But that only gave it 20 seconds of footage. I don’t know how many people’s attention it could capture with that short piece of film. But now it doesn’t even claim any longer that it is destroying a site. It gets human rights groups and the UN to say so. First, people are reported as hearing ‘explosions’. The planet then has the footage that it releases according to its own schedule.”

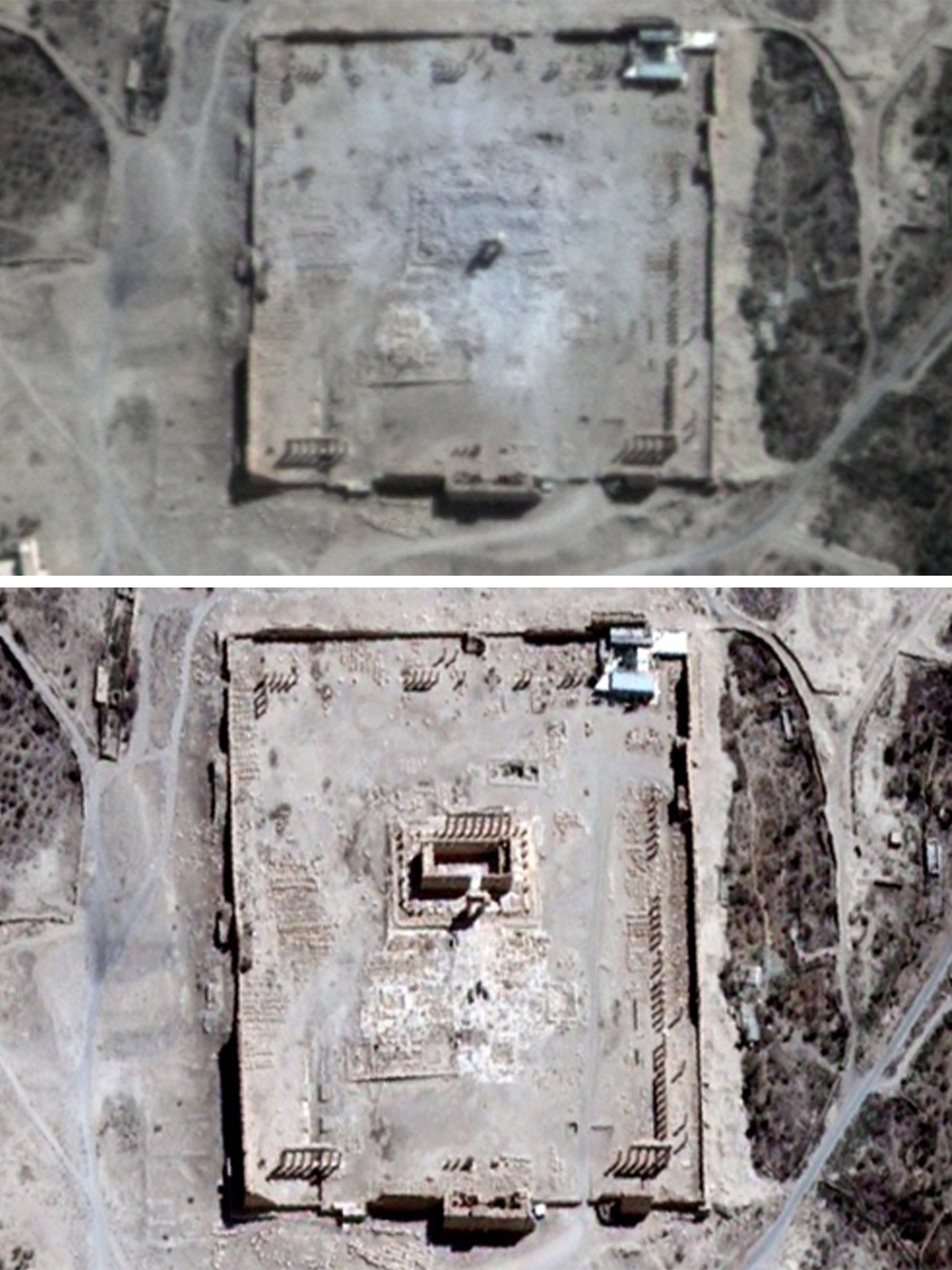

For this reason, Ms Farchakh says, Isis does not destroy all of Palmyra in one video. “It started with the executions [of Syrian soldiers] in the Roman theatre. Then it showed explosives tied to the Roman pillars. Then it decapitated the retired antiquities director, al-Asaad. Then it blew up the Baal Shamim temple.

“And then everyone shouted, ‘Oh no – what will be next? It will be the Bel temple!’ So that’s what it did. It blew up the Bel temple. So what’s next again? There will be more destruction in Palmyra. It will schedule it differently. Next it will move to the great Roman theatre, then the Agora marketplace [the famous courtyard surrounded by pillars], then the souks – it has a whole city to destroy. And it has decided to give itself time.”

The longer the destruction lasts, Ms Farchakh believes, the higher go the prices on the international antiquities markets. Isis is in the antiquities business, is her message, and Isis is manipulating the world in its dramas of destruction. “There are no stories on the media without an ‘event’. First, Daesh gave the media blood. Then the media decided not to show any more blood. So it has given them archeology. When it doesn’t get this across, it will go for women, then for children.”

Isis, it seems, is using archeology and history. In any political crisis, a group or dictator can build power on historical evidence. The Shah used the ruins of Persepolis to falsify his family’s history. Saddam Hussein had his initials placed on the bricks of Babylon. “This bunch [Isis] decided to switch this idea,” Ms Farchakh says. “Instead of building its power on archeological objects, it is building its power on the destruction of archeology. It is reversing the usual method. There will not be a ‘before’ in history. So there will not be an ‘after’. They are saying: ‘There is only us’. The people of Palmyra can compare ‘before’ and ‘after’ now, but in 10 years’ time they won’t be able to compare. Because then no one will be left to remember. They will have no memory.”

As for the Roman gods, Baal had not been worshipped in his temple for 2,000 years. But it had value. Ms Farchakh says: “Every single antiquity [Isis] sells out of Palmyra is priceless. It is taking billions of dollars. The market is there; it will take everything on offer, and it will pay anything for it. Daesh is gaining in every single step it takes, every destruction.”