Is the new female Viagra just another attempt to banish our woes with the quick fix of pills?

The anti-pharmaceutical puritans can sound not merely utopian, but heartless too

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.“The great question,” mused Sigmund Freud in 1925 to one of his star disciples, “which I have not yet been able to answer, despite my 30 years of research into the feminine soul, is ‘What does a woman want?’”. He flung that much-derided query at Princess Marie Bonaparte, aka Princess George of Greece and Denmark. Quite apart from her trail-blazing achievements as a psychoanalyst, Princess Marie was also the protector and landlady in 1920s Paris of her husband’s nephew and his family, exiled from Greece. She was fond of the boy, whom we know as Prince Philip. When not looking after the future Duke of Edinburgh, Marie Bonaparte began to explore the causes, and potential cures, of sexual dysfunction in women under the pseudonym of “AE Narjani”.

Princess Marie lived long enough to see the surprise upturn in her little kinsman’s fortunes: she attended the Coronation in 1953. Would she have been even more startled to discover that, 90 years after she began asking questions about the female libido and its discontents, an answer should arrive in the shape of a pink pill?

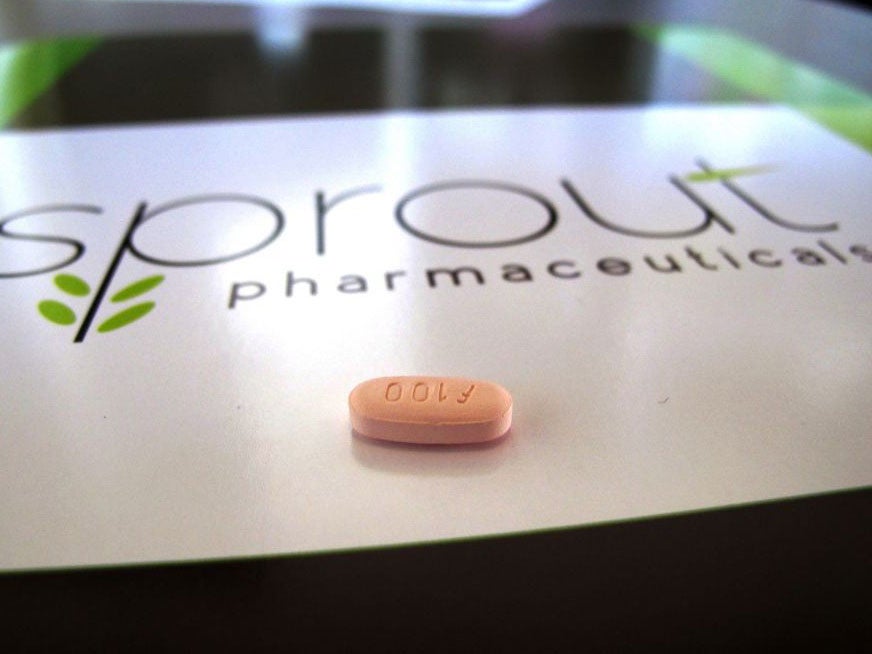

This, allegedly, is what a woman wants. America’s pharmaceutical gate-keeper the FDA (Food and Drug Administration) has just licensed a treatment for low female libido, generically designated as “flibanserin” but cutely marketed as “Addyi”. Rejected twice before by the FDA, and only approved after a spilt vote (18-6), Addyi can now be prescribed in the US from October following a propaganda campaign by its manufacturer.

Sprout Pharmaceuticals tweaked the push for recognition into a gender-equality issue. The firm and its media cheerleaders called on the FDA to “Even the Score” with Viagra, the remedy for male erectile problems accidentally discovered by Pfizer in Kent. But Viagra, which has a narrow neurovascular target, does not pretend to address low libido: the “female Viagra” tag is pseudo-scientific bunkum.

With their previous company Slate Pharmaceuticals, Sprout bosses Cindy and Bob Whitehead attracted a damning “warning letter” from the FDA in 2010. It castigated them for making “misleading” claims about a testosterone pellet, Testopel, stating it was “extremely concerned by the breadth and scope of violations” in its promotional materials.

Nonetheless, after the FDA ruling, it didn’t take long for Sprout’s finances to reach what the Victorian doctors who treated “hysterical” women patients would have referred to as a “paroxysm”. On Thursday, Valeant Pharmaceuticals of Canada promptly bought the firm for $1 billion. If not the earth, then at least the share-price moved for Sprout.

Does Addyi’s licensing mean a triumph for equal access to desire-enhancing drugs? Its roll call of contra-indications looks longer than anything the most hopeful Viagra client might imagine. The pill turns out to be entirely incompatible with any alcohol, with a high risk of blackouts. Trust the US pharmaceutical industry to try, after millennia of drunken dalliance, to smash the hallowed liaison between lust and grog. More crucial for anyone who thinks that Marie Bonaparte’s tradition of the “talking cure” still has some validity, the FDA insists that the tablet cannot address “problems within the relationship”.

That relationship, as common human sympathy if not pseudo-medical hocus-pocus will grasp perfectly well, may extend beyond a significant other to take in family, friends, job and even society. Libido can track events not only in the body, and of course the home, but in the body politic. No one with a grain of compassion should scoff at serious research into the “marked distress” that Addyi seeks to alleviate. Yet the pill in itself may not treat the ill. Evening the score, the same certainly goes for men. How many problems that run deeper than sluggish blood vessels has Pfizer’s fail-safe blue booster masked?

Whatever happens to Sprout’s new-fangled aphrodisiac, it could never arrive in the surgery without the stranglehold of psychiatric medicine over American ideas about the human condition. Sprout bought flibanserin from its former owner, Boehringer Ingelheim, knowing that “generalised hypoactive sexual desire disorder” (HSDD) had a place within the DSM manual of psychiatric conditions that governs US clinical practice. Once listed in DSM, a “disorder” can be treated with a stronger expectation that insurers will cover the costs.

In fact, DSM-5 – the latest redaction of this soul-mechanic’s under-the-bonnet handbook – has since 2013 redefined the relevant malady as “female sexual interest/arousal disorder”. In its scattergun hubris, DSM not only pathologises everyday unhappiness. It shrinks the brilliant spectrum of ordinary human feeling into the gunmetal grey of the blister-pack and the consulting room. One especially contentious change in DSM-5 is the removal of the so-called “bereavement exclusion” from its list of depressive disorders. In other words, it now treats prolonged grief for a loved one as an illness that requires medication.

Thankfully, this reductive lexicon has always had its heretics. After the fifth edition appeared, the British Psychological Society rightly objected to its many diagnoses “based largely on social norms”, and warned of the “continuous medicalisation” of “natural and normal responses”. The BPS even dared to cite “poverty, unemployment and trauma” as sources of suffering – an aetiology that applies just as much to the “HSDD” that Sprout now seeks to mitigate. Tell that to the pill-peddling shrinks. Among the task force of doctors which revised DSM this time, 69 per cent had ties to the pharmaceutical industry.

No one has who has felt, witnessed or tried to assuage the wrenching pain of, say, clinical depression or bipolar disorder will take a hard-line abstentionist position on drugs. Now refined into smarter, lighter instruments, anti-psychotics bring hope and relief to millions. On a lower level of anguish, the anti-depressant Prozac, Big Pharma’s miracle potion of the early 1990s, appears on around six million UK prescriptions every year. Other SSRI drugs (“selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors”) likewise flow through the medical mainstream.

Yet widespread side effects still darken this sunnier picture. Curiously, for fluoxetine (Prozac) and its family, the most common downside turns out to be: yes, sexual dysfunction. In some studies, up to 60 per cent of subjects reported loss of libido. It may be worth asking how many potential users of Addyi – or current clients of Viagra – have also been taking SSRIs. As Grace Slick sang with Jefferson Airplane in ‘White Rabbit’, during the late-Sixties cult of purely recreational highs, “One pill makes you larger, and one pill makes you small”.

Every 20th century generation has dived down its own rabbit-hole in search of a happiness tablet. In high culture, the pursuit gets a bad press, with the scornful tone set by Aldous Huxley in Brave New World (1932). Soma, the soothing panacea that keeps his drones docile, is always on hand “to calm your anger, to reconcile you to your enemies, to make you patient”. In Huxley’s rhyme, “Was and will make me ill/ I take a gramme and only am.”

In the hunt to put “was and will” to sleep, one experimental track tends to runs within the law, another outside it. Half a century ago, the use of barbiturates and benzodiazepines (‘Mother’s Little Helper’, as the Rolling Stones sang) often shuttled back and forth across a legal line. Twenty years ago, the Prozac vogue coincided with the spread of MDMA (ecstasy) through the club scene. Like suspicious half-siblings, street drugs and licensed drugs often nod warily to one another. New research suggests that MDMA itself – in a pure form, not the cut toxic sludge clubbers buy – may outperform SSRIs as a treatment for post-traumatic stress, especially when combined with psycho-therapy.

In the modern chapters of our ancient quest for peace or bliss, talking cures and medical or chemical solutions have often gone hand in hand. No one extolled the therapeutic virtues of cocaine more fervently than the young Freud. His 1884 paper Uber Coca pays tribute to the opiate. The couch has often come to terms with the powder and pill – even, sometimes, with the knife. Marie Bonaparte sought to heal her own “frigidity” via a procedure – the “Halban-Narjani operation” – that today we might classify as elective female genital mutilation (FGM).

Whether surgical or chemical, every silver bullet in the psychiatric armoury eventually misfires. Odds on that Addyi will as well. As Lisa Appignanesi writes in Mad, Bad and Sad, her history of “women and the mind doctors”, “it is as if the greater the terrain of possible malaise, the more ‘scientifically’ and organically precise we would want the cause and cure to be”. From “hysteria”, repression and depression to the general “dysfunction” that has already made a billion for Sprout, symptoms and diagnoses, as Appignanesi notes, “cluster to create cultural fashions in illness and cure”.

Yet the anti-pharmaceutical puritans can sound not merely utopian, but heartless too. The danger with the sort of humanistic piety that steers unhappy women, or men, away from pills is that it orders sufferers to change their world when they struggle to get by. So don’t blame the patient who seeks comfort, satisfaction or even transcendence within a foil wrap. But do ask why comparably effective kinds of drug-free talking treatment – even humble, short-term CBT (Cognitive Behavioural Therapy), which hard-core Freudians often dismiss – so seldom win the public funds to match the siren calls of Big Pharma. When they do, that really might begin to even out the score.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments