Iran: Lifting of sanctions is a positive step, but wealth could empower hardliners

In the best of worlds this move would lead to a massive investment programme that improves the lives of ordinary Iranians

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The implementation of the landmark 2015 nuclear agreement with Iran, and the lifting of crippling sanctions against Tehran, is a rare piece of good news in an international landscape scarred by political and now economic disorder – nowhere more so, of course, than the tormented Middle East, where Iran plays, for better or worse, a crucial role.

Indubitably, the world is a safer place now that Tehran’s ability to build a nuclear weapon has been significantly put back and intrusive inspection powers make cheating far harder. Meanwhile, the opening up of a country of some 80 million people with a desperate need to modernise – and now with the ability and the wherewithal to do so – offers a major new market in a slowing global economy. Companies from the major industrialised nations are already jostling to take advantage.

And in the long term, perhaps most importantly, it is to be hoped that the deal will strengthen the reformers around President Hassan Rouhani who want to make Iran a more “normal” country, no longer a pariah but playing a role in the world befitting its rich past and immense potential. Mr Rouhani hailed the nuclear deal as a “golden page” in Iranian history, and will carry that message of engagement when he visits France and Italy next week.

But the rapprochement remains fragile, evidenced not least by the bizarre fact that at the very moment the nuclear sanctions disappeared, another set of sanctions – admittedly far less punitive – was imposed by the US to punish Tehran for its violation of UN curbs on ballistic-missile development. Iran’s dismal human rights record, too, is a constant irritant to relations.

All of this reflects the inconvenient truth that decades of political bickering and feuding have not altered reality. Ultimate power in Iran rests not with the President, but the country’s Supreme Leader, Ali Khamenei. Under his aegis, a hardline faction is able to use every opportunity to undermine the moderates.

The lifting of sanctions, and the release to Iran of $50bn (£35bn) or more of frozen funds, would in the best of worlds lead to a massive domestic investment programme that improves the lives of ordinary Iranians. But there is strong reason to fear that some of it, at least, will go towards fuelling conflicts in the region, from Syria and Yemen to the Hezbollah and Hamas insurgencies against Israel.

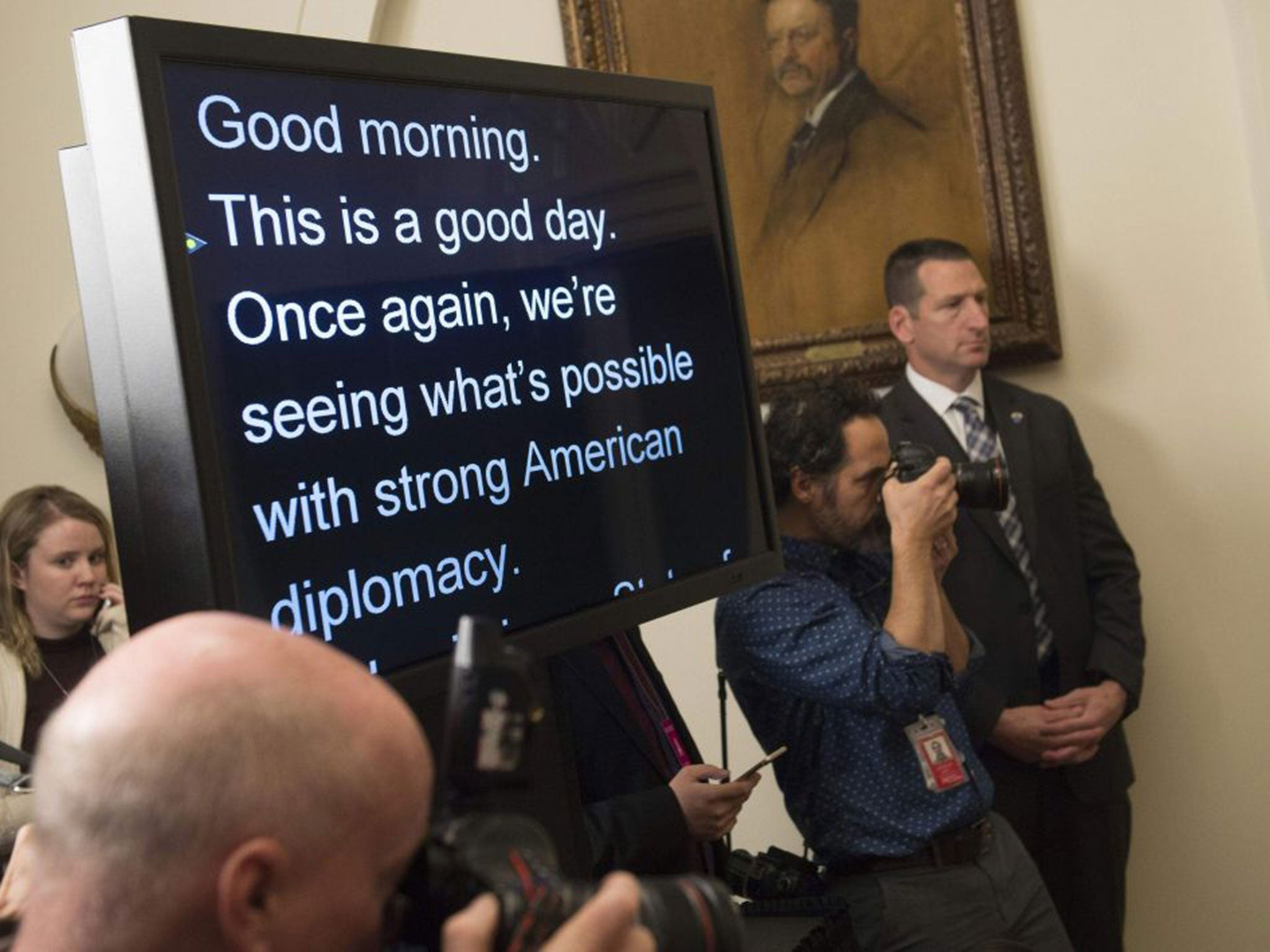

Barack Obama hailed completion of the nuclear agreement as proof of what “smart, patient and disciplined” diplomacy can achieve. But all that and more will be required to make a success of the new priority – of persuading Iran to take a more constructive approach to the interlocking and hideously complicated crises that grip the Middle East.

There are avenues of promise, not least that as a Shia power Iran is a de facto ally of the US in the struggle against the Sunni jihadists of Isis. But that must be set against Iran’s support for President Assad which has prolonged the Syrian tragedy, and its deepening rift with Saudi Arabia and the Sunni states of the Gulf.

The hope is that the moderates led by President Rouhani, backed by a younger generation of Iranians thirsting to rejoin the world, will adopt this more constructive approach. But if tangible economic improvements fail to materialise, public discontent may give hardliners an opportunity to hit back. Iran, in short, remains unpredictable, to a large degree unknowable. “Trust but verify,” was Ronald Reagan’s watchword during the arms negotiations of the 1980s with the Soviet Union. Despite the nuclear deal, Iran demands, if anything, even greater vigilance today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments