Inequality has less to do with your income, as you might expect, and more to do with who you've married

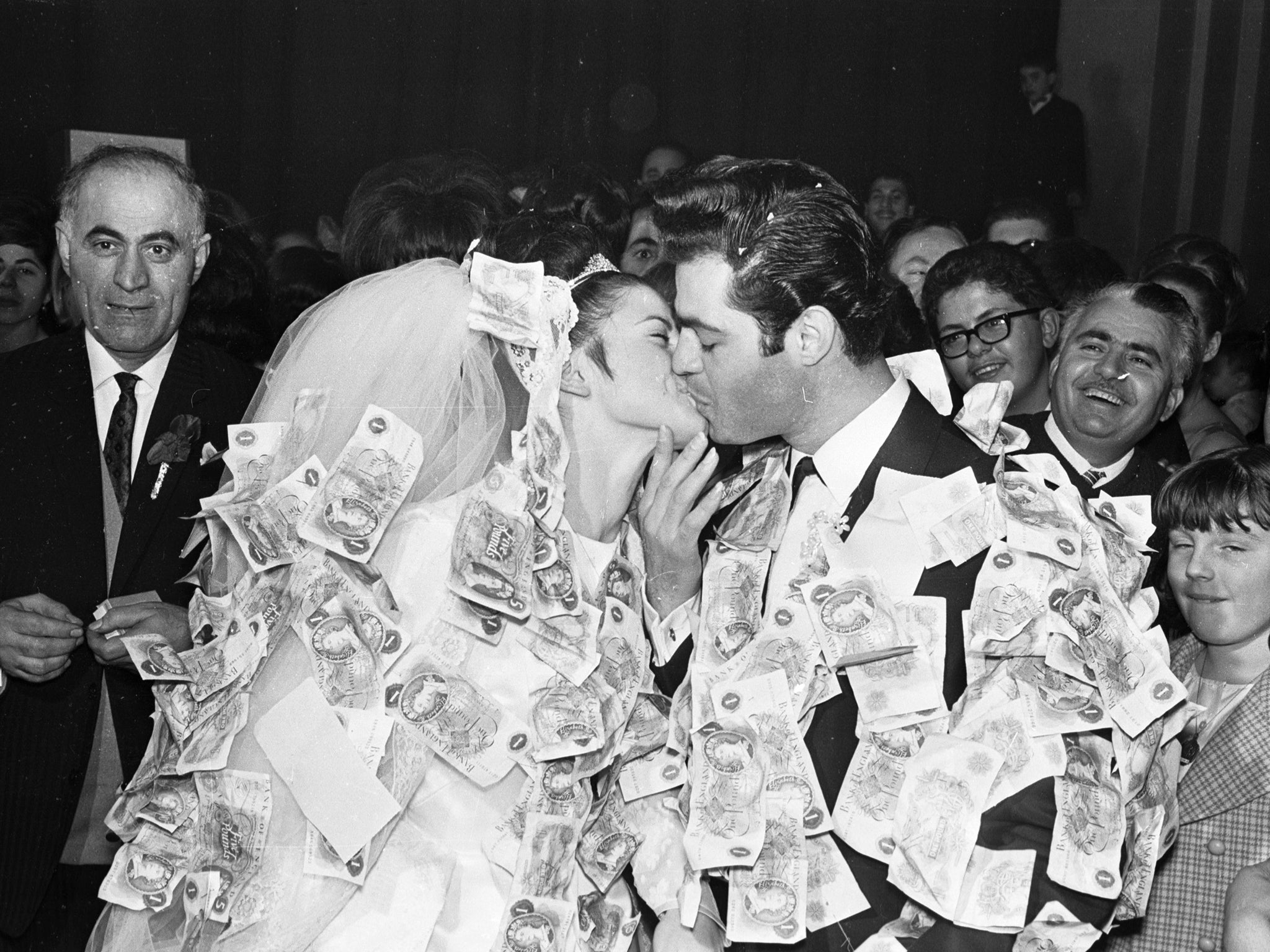

One of cause of inequality is assortative mating. No, this is not a new dating app, it is the increased tendency for people with similar backgrounds, jobs, or levels of education to mate with each other

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Ask most people what they think is happening to income inequality in Britain and they would reply that it was increasing. Most people would also think it was increasing everywhere, from China to the United States, and every story about how rich people hide their wealth in places like Liechtenstein and Panama reinforces that view.

The trouble is that this is wrong – or at least wrong in two important ways. The ways in which inequality is increasing, particularly in the UK and US, has nothing to do with people’s incomes, but to do with their wealth and life choices, something that is much harder for governments to influence. Indeed, a study by the Office for National Statistics (ONS) published on Friday showed that income inequality has barely changed over the past 25 years.

If you take pre-tax income, there has been hardly any overall change since 1990 and, if you take post-tax income, inequality in 2014-15 was somewhat lower than it was in 1990. Prior to 1990 there was indeed a sharp increase in inequality of income both before and after tax, with the inequality starting to creep up before Margaret Thatcher won the 1979 election. However, during the 1960s and 1970s there had been a big squeeze on differentials (some of us remember the £6-a-week cap on wage increases) and this sharp rise through the 1980s must to some extent have been a reaction to that. Since 2007-08 inequality has been coming slowly down.

These calculations are based on different measures of the Gini coefficient, and allow for all the different ways in which government intervenes through its tax and benefits system. As a rule of thumb, income tax has been increasingly successful at narrowing differentials but to some extent that has been offset by higher revenues from other taxes, especially VAT.

The ONS comments: “Before any taxes and benefits, the UK had one of the highest levels of income inequality in the EU. However, the UK’s tax and benefits system appears to be more redistributive than that of many other countries with relatively high pre-tax and benefits inequality, bringing the UK close to the overall EU average for inequality of disposable income.”

If the picture of income inequality is one of broad stability, there are a number of other aspects of inequality where the gap is clearly widening. One of the most troubling in the UK is wealth. That is beyond this particular ONS study, but it notes that inequality of wealth is double that of income. The surge in house prices will have been behind the most recent increase, and quite aside from what is happening to the country as a whole, there will have been a divergence between London and the South-east on the one hand and the North and Scotland on the other. It is difficult to do anything about wealth inequality, short of confiscation or much higher taxes on home ownership, which would be politically very difficult to sustain.

It is even harder still to tackle changes in social behaviour that have the effect of increasing inequality in society. One of the most interesting changes that has taken place is the rise of what is called assortative mating. This is not a new dating app, it is the increased tendency for people with similar backgrounds, jobs, or levels of education to mate with each other.

This in itself is hardly surprising. People who meet each other at university often go on and have families together. However, as university education has grown and as women have, to a much greater extent, had professional careers, there has been a huge social shift. In the US in 1960 a quarter of men with university degrees married women with degrees. In 2005 nearly double did. Had it not been for this shift there would have been hardly any increase in inequality in the US over that 45 year period.

That is in the US. I have not seen a comparable study for the UK but it would be surprising if our experience were so very different. You would expect a similar pattern to be happening elsewhere, for in much of the world university education is rising even faster than here, and just about everywhere the premium on education has risen. Thus graduation rates in Poland and Korea are higher than in the US or UK.

It is hard to see what any government can do about this. It cannot tell people not to pair up with people similar to themselves. The big message, surely, is to acknowledge that inequality is not just about income. It is much more complex and multi-layered than that.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments