Let 2017 be the last year that women have to take responsibility for the sins of men

When women knowingly excuse abuse, we should criticise them in response. But to expect women to take on full responsibility for the sundry actions of all the men they have ever known or worked with is deeply unfair

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.“Behind every great man is a great woman”. In 2017, this mantra appears to have been turned on its head. In a year plagued by abuse scandals, the nature of much of the press coverage would have us believe that behind every bad man is a bad woman.

As each (male) accused abuser is exposed, it’s only a matter of time before we clamour to condemn the women with whom they’ve been associated. I’ve often found myself wondering: is it necessary to discredit women who have been apparently abetting abuse, or does it reflect the insidiousness of sexism that male crimes need to be discussed in the context of female shortcomings?

The answer to this question isn’t straightforward but, by looking back over some of the scandals of the last year, we can potentially draw conclusions about when it is, and isn’t, appropriate to criticise women in relation to the behaviour of their male associates.

Donna Karan was quick to come to the defence of Harvey Weinstein when the allegations that rocked Hollywood, politics, and indeed the whole world were in their relatively early stages. The DKNY founder was widely chastised for telling the Daily Mail that Weinstein was “wonderful” and that women who dressed a certain way were sometimes “asking for it”.

What Karan said rang extremely sexist, despite her being a woman herself. Possibly for this very reason, her comments were equated with the damaging attitudes of her male counterparts. But everyone seemed to forget that Karan was not just “part of the problem” – she was also one of its victims. Her troubling words did appear to excuse abuse, but she spoke with such a flagrant disregard for her own sex, such open and unashamed support for patriarchal standards, that rather than feeling angry at her, I wanted to invite her over for a cup of tea and ask her about what she’d been told, or what she’d experienced, that had led her to believe she and women like her deserved so little respect.

But, when it came to Lena Dunham’s defence of her friend Murray Miller, I was less keen to offer up a brew.

Admittedly, it was worryingly foreseeable that Dunham was going to be on the receiving end of much of the criticism that would have been more appropriately directed towards the accused. However, Dunham had set herself up as an authority on sexual assault. She firmly espoused that all women should be believed, memorably tweeting: “Things women don’t lie about: rape”. Then she misused this authority to discredit the claim of Aurora Perrineau.

Dunham solidified her support of Miller in the wake of Perrineau’s accusations, and used her privilege to undermine a woman who the public were going to be less willing to believe, partly because of her race. Dunham’s statement had the ring of “One rule for women like me, another for women like you”. This inappropriate response wasn’t the pitiful product of internalised sexism; it was an abuse of power. And abuses of power need to be checked.

JK Rowling was also speaking from a position of privilege when she excused the behaviour of actor Johnny Depp. Given that Harry Potter holds a near-scriptural significance in my life, I was the last person who’d be queueing up to criticise JK. But despite the fact that Depp’s ex Amber Heard had previously said, “During the entirety of our relationship, Johnny Depp has been verbally and physically abusive to me” (a claim that was substantiated by texts, video footage and pictures of Heard’s bruised face), Rowling still wrote a statement in support of Depp and backed him taking up the main role in one of her films.

But there is an important difference between rebuking a woman who has knowingly used a position of power while disregarding or ignoring a victim and criticising women who have, in ignorance, associated with men who have later turned out to be assailants.

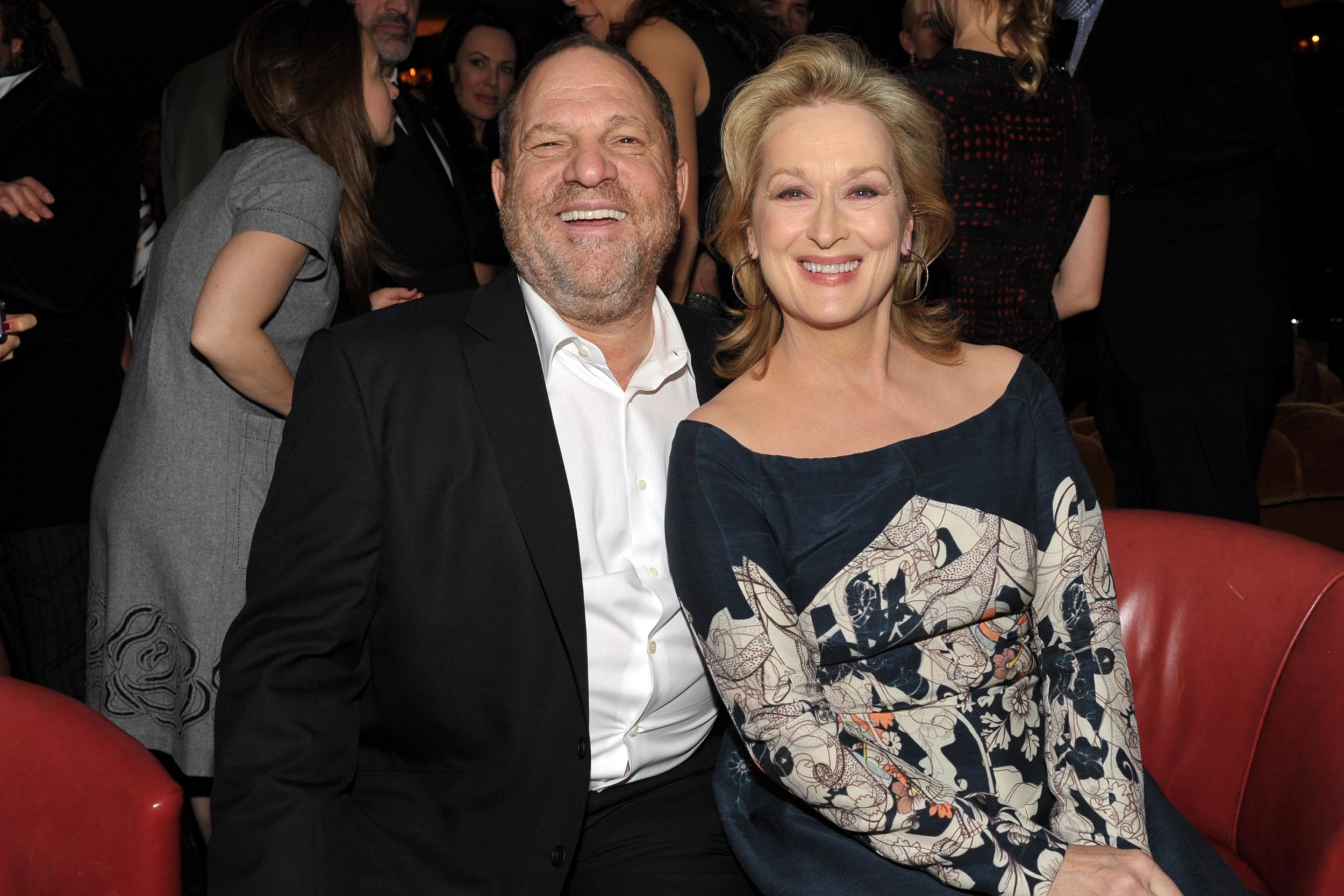

Recently, pictures of Meryl Streep next to Harvey Weinstein were plastered across Los Angeles, with the words “She knew” covering the actress’s eyes. Streep was accused by Rose McGowan of having knowledge of Weinstein’s predatory nature, and Streep has since responded, explaining: “I did not know about Weinstein’s crimes … I don’t tacitly approve of rape.”

When women knowingly excuse abuse, we should criticise them in response. But to expect women to take on full responsibility for the sundry actions of all the men they have ever known or worked with is deeply unfair. It’s more than unfair, in fact – it’s the patriarchy’s dream come true.

So perhaps we should all make a joint New Year’s resolution: In 2018, we will no longer blame the attitudes, attire or approach of women for the sexual, physical and emotional abuse perpetrated by men. Let the perpetrators answer for their crimes, rather than the nearest women to them.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments