Investigations after Grenfell have revealed that London's housing market is a global centre for dirty money

A document released apparently in error by RBKC provides the details of some of its housing which is owned by oligarchs and kept empty. Last year, some of the buildings were included in a series of coach trips – 'Kleptocracy Tours' – organised by a Russian expatriate to expose London as a destination for questionable foreign money

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Almost two months on, most of its surviving residents still wait for the permanent new homes they were promised; the traumas and tragedies of that June night remain real. But across the capital, if not the country, Grenfell Tower now means more even than that vast conflagration in which more than 80 people died. Its charred hulk has become a cypher for all the ills that afflict London.

From the sharp wealth divide to the neglect of social housing; to the unaffordability for many of a decent home; to the safe haven it provides for dubiously acquired, often foreign, money; to the “light touch” regulation which clearly contaminated building safety as well as banking; to the greed, if not actual corruption, behind planning decisions; it is hard to find much to like in the way London has developed in the past 20 years. At a time when so many other big European cities have regulated and invested for quality of life, London exemplifies in so many respects the very opposite.

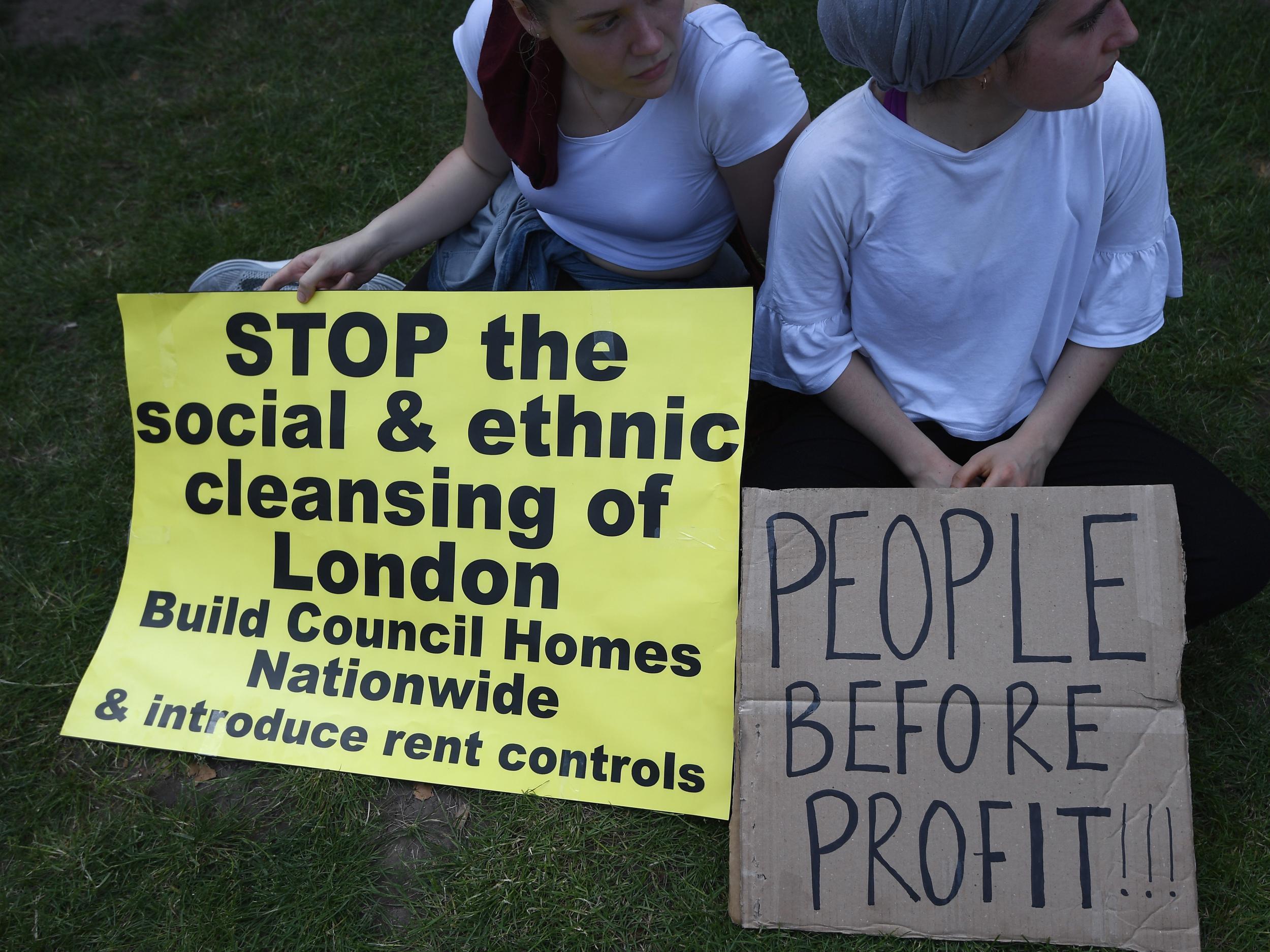

The latest chapter of the Grenfell Tower inquest, as it is being conducted at popular level, concerns the scandal of empty accommodation, including in the very same borough as the estate that included Grenfell Tower. Jeremy Corbyn’s call for such housing to be requisitioned for the benefit of former Grenfell residents might have been widely ridiculed as an echo of failed communism, but it struck a chord. What is more, it seems to have shamed the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea (RBKC) into buying up a whole block of flats that was nearing completion to house some of the Grenfell homeless.

This move alone should demonstrate that there are things that can be done to provide more relatively low-cost housing in London, but it all depends on whether central and local government want to find remedies, which – even after Grenfell Tower – is by no means evident. And while empty housing is an obvious place to start, it has different layers that need to be tackled in different ways.

Let’s start at the “oligarch” end of the scale. Thanks to a document released, apparently in error, by RBKC, details of some unused homes in the borough and who owns them are now public (although not all the information was accurate). The vacant properties include some awaiting, or in the process of, redevelopment – including the site of a disused tube station which has remained derelict since its purchase by the Ukrainian oligarch, Dmytro Firtash, who is in Switzerland fighting extradition to the US. There is also a completely empty mansion block, which – according to the owners, the Candy brothers (of the hideous and largely unoccupied One Hyde Park fame) – awaits planning permission for redevelopment.

Last year, as it happens, some of the same buildings were included in a series of coach trips – “Kleptocracy Tours” – organised by a Russian expatriate, Roman Borisovich, to expose London as a destination for questionable foreign money. But the vacant mansions and penthouses of oligarchs and their ilk are never likely to be freed up for social housing. The problem here is less that so many stand empty than that their owners were allowed to buy them in the first place.

It is all very well proclaiming that London is “open for business”, but should we not be more fussy about the sort of business? There is a mass of money-laundering and anti-corruption legislation, but how much of it is actually used to identify or confiscate ill-gotten gains, or the lawyers and financiers right here who facilitate the multi-million pound purchases? Other cities and countries seem better at deterring, if not detecting, dirty money. Some restrict property ownership to citizens. Some impose swingeing charges on unused premises. London and the UK could do, too.

London could do more to manage other parts of the market, too. From the kitchen of our flat, we can see the ribbon of new high-rises that have sprung up over the past 10 years along the south bank of the Thames. How, you wonder, when all this is complete, could London possibly have a housing shortage? But, of course, it is the “wrong” sort of housing. If, as is not impossible, London has built itself a glut of million-pound two-bed flats, what then?

Do prices fall to the point where these flats are “affordable”? If so, do those largely foreign investors with multiple “units” take fright? Could more “Londoners” decide to buy them? Might some of the blocks be bought up for social housing? There is no reason why much of this land should not have been redeveloped, but many cities elsewhere in the developed world would have kept a far tighter rein on developers, in terms of purpose and design. Will London ever be prepared to do the same?

As for those sky-high prices, they are not just a reflection of shortage. Successive governments may have paid lip service to “the market”, even as they rigged it in so many ways. “Right to buy” without “duty to replace” depleted the social housing sector, and has now been absurdly extended to housing associations. Initially restricted to long-time residents, discounts soon applied to tenants of barely two years’ standing, making the allocation of a council flat in a high-price area even more of a bonanza than it already was.

“Buy to let”, designed to remedy a real shortage of rental housing, has grown into an under-taxed monster which distorts the lower end of the market. Only now are big investors starting to emulate the US and continental model of long-term, professionally managed, in-town blocks. Why were the tax breaks not directed towards this sort of development? Was a patchwork of amateur landlords really a better solution?

And now, just as a saturated London market might finally be pushing prices down, there is a combination of “help to buy” schemes and ultra-low mortgage rates – both, in the end, political decisions – which seems calculated to push prices higher. It does not have to be like this. But so long as it is, any penalty for leaving property vacant will be offset by the expected capital gain.

The super-rich have more freedom than most to choose where they live, and that freedom cannot be taken away. But they are not the only guilty party in the scourge of empty homes. Elected governments and councils also have choices. They can choose how to regulate in their domain. They can decide on their planning criteria, their tax provisions, on who has access to the market and on what conditions. If they have not turned their attention to the empty housing in their midst, it is because they have seen no imperative to do so. Maybe Grenfell Tower will help change their minds.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments