French nuclear power plant failures: There can be no margin for further error

Whatever the outcome of further tests ordered by the French watchdog, Areva has to convince the Office for Nuclear Regulation that it knows what it is doing

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

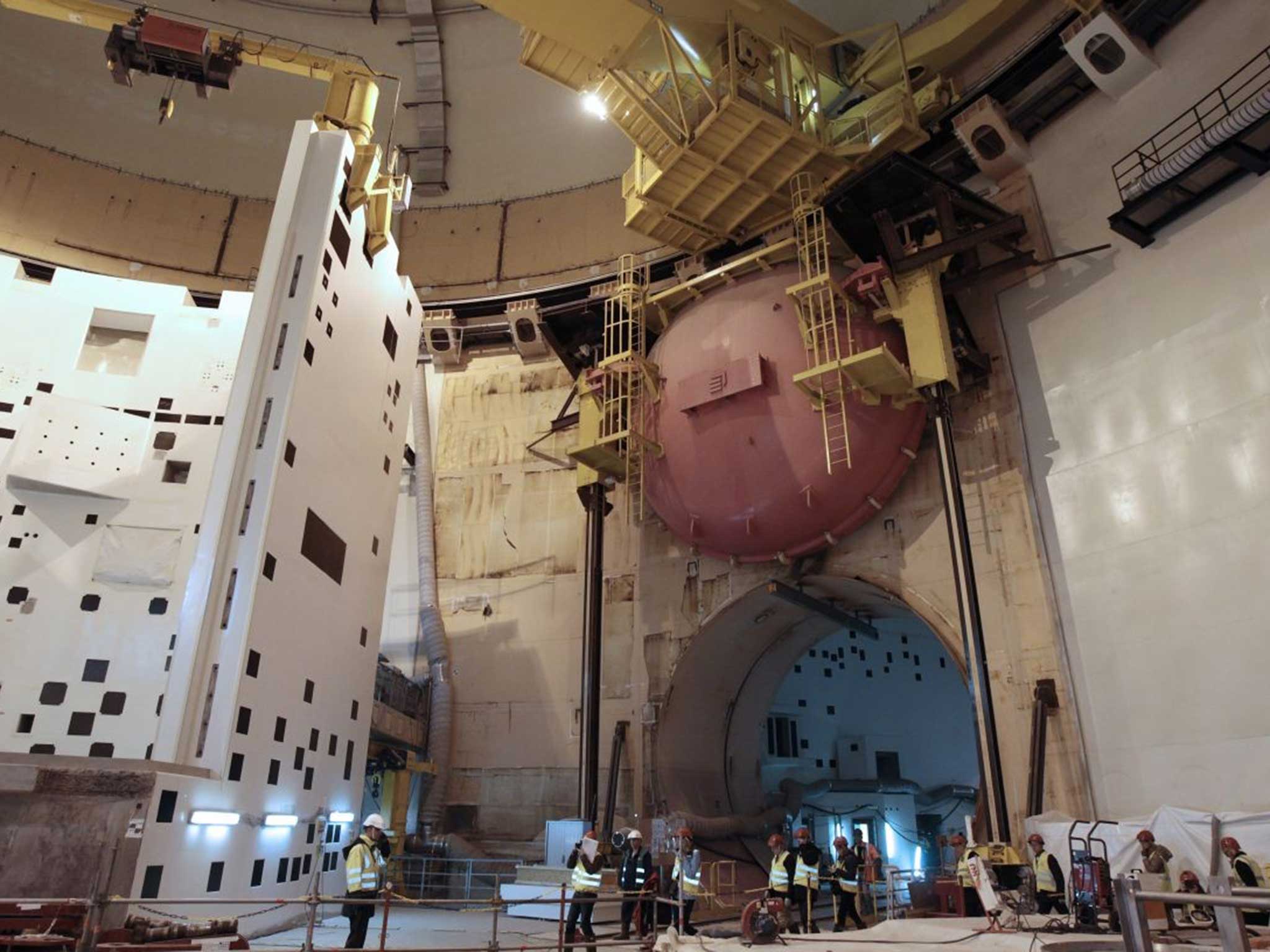

Your support makes all the difference.The steel pressure vessel of a nuclear power plant is the first and main containment that holds the nuclear fuel safely, and so is one of the most critical of the many components of a pressurised water reactor. A fault in this part of the EPR reactor could undermine its credibility in delivering the new Hinckley Point reactors, not just on time and to budget, to the required safety level.

Pressure vessels of nuclear reactors are prone to something called “embrittling”, when the neutrons released during the chain reactions damage the thick steel plates that are welded together to form the cylindrical pressure vessel and its top and bottom – the “vessel head” and the “vessel bottom head” respectively. It appears that chemical and mechanical tests conducted at the end of last year on a vessel head similar to the one at Flamanville discovered “anomalies” in the composition of the steel. Similar anomalies were also found in the vessel bottom head indicating that too much carbon had been added to the steel when it was forged.

The problem now for Areva and the French nuclear watchdog is assessing whether these anomalies will affect the strength of the pressure vessel not just in routine operation, when it is being bombarded by embrittling neutrons, but also in the unlikely event of something called pressurised thermal shock, which occurs in some accident scenarios when cold water enters the pressurised reactor. If the pressure vessel at Flamanville has to be replaced – which is theoretically possible, although expensive, because it has not yet been irradiated with nuclear fuel – it would cast serious doubts over the new reactors at Hinckley and Sizewell, which were to be built by Areva.

It is no exaggeration to say that questions over the safety of a nuclear reactor’s steel pressure vessel can undermine confidence in the project. Whatever the outcome of further tests ordered by the French watchdog, Areva has to convince the UK watchdog, the Office for Nuclear Regulation, that it knows what it is doing.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments