E L James's book Grey is a reminder of how the phenomenon of the best-seller works

It's hard to understand why so many are buying it – but then best-selling was ever an inexact science

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The journals of the late-Victorian savant Samuel Butler contain an instructive episode in which the diarist travels by train across the English countryside. At one point, looking out of the window, he spots a calf which, temporarily detached from its mother, is making a light breakfast of a pile of dung. At first the spectacle worries Butler. Why should an animal nurtured on bright green grass want to eat something so patently unwholesome as a stack of manure? Then the answer strikes him. No one has told the calf that eating dung is not a good idea. All it needs is some education.

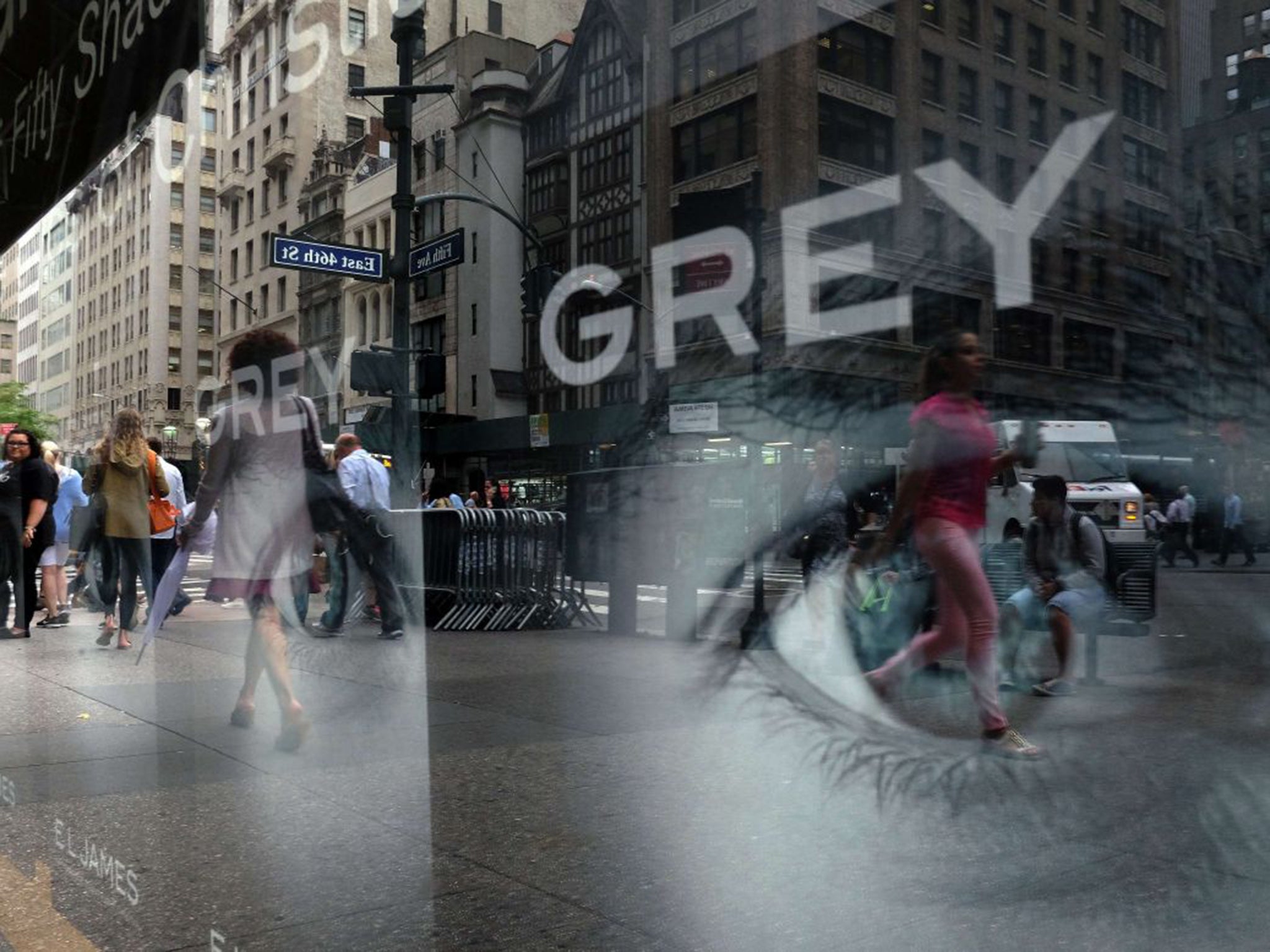

The memory of this paragraph rose into my head at the precise moment last week when, under the sardonic gaze of the man at the front desk at Hatchards, and murmuring that I was only buying it “for professional purposes”, I shelled out for a copy of E L James’s monumentally best-selling Grey. On the journey along Piccadilly I had, as it happened, passed a woman bearing a copy away in triumph. And simultaneously, another recollection stirred, which was of standing on the platform at Notting Hill tube station on the day that the first volume of Margaret Thatcher’s memoirs, The Downing Street Years, appeared in the bookshops and counting the number of passengers who were going home with one. No doubt about it, I thought, in terms of public visibility, E L can give Mrs T a run for her money,

The altogether prodigious success of Ms James’s latest dispatch from the S&M dungeon – 647,000 copies sold in the first three days – has provoked a certain amount of alarm, or occasionally satisfaction, among the commentariat, on the grounds that, whether we like it or not, here is an example of genuinely popular taste making its presence felt. My colleague David Thomas on our sister-paper The Independent wrote a rather anguished piece alleging that the large number of people keen to pronounce that Fifty Shades of Grey is appalling are concealing their true beliefs. “Secretly, when no one’s looking, they think it’s brilliant. And consider this,” Thomas provocatively concluded, “they might be right.”

It’s no disrespect to Mr Thomas, or to the self-evident truth that there are no finite standards in the arts, to say that he can’t possibly believe this, for no reader with the slightest feeling for literature (and here I am already using hopelessly prejudicial terms like “feeling for literature”) could. It is not that, from my doubtless Olympian viewpoint, Grey is badly written, or psychologically unconvincing, or creepy, or – a much worse failing – entirely humourless, or that one leaves it with a sneaking feeling that Ms James may have been having a bit of fun sending herself up. No, these are all value judgements which I wouldn’t dream of inflicting in an increasingly relativist age, on an audience capable of stating its own cultural preferences without the aid of self-appointed and no doubt elitist critics.

But to imply, as Mr Thomas and one or two other like-minded souls in the popular press seem to be implying, that a) this is an example of popular taste in action, and b) that the number of copies sold of a book or record or DVD proves some point about cultural merit, and that volume sales will always have the edge on discrimination, is merely historically inaccurate. On the one hand, a genuinely popular taste, which might be defined as a group of people with shared cultural standards arriving independently and through the exercise of their intelligence at a common judgement, no longer exists. It perished at the end of the 19th century in the wake of universal literacy and the rise of a publishing industry keen to satisfy this new public’s presumed wants: all we have now is a mass-market preference, imposed upon us from on high.

On the other, arguments about numbers rarely take into account wider cultural resonance. Certainly, a trawl through the record sales of the 1960s will nearly always demonstrate, let us say, that The Sound of Music outsold Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, or that Engelbert Humperdinck shifted more singles than the Rolling Stones; but in terms of cultural impact Engelbert and Rodgers and Hammerstein invariably end up taking a back seat. It is the same with the late 1970s. Of course, Fleetwood Mac’s Rumours outsold all the punk bands by 10 to one. Of course all the excitement about the “New Wave” was a conspiracy got up by the music press. Of course, the nation’s youth were really grooving to disco rather than the Sex Pistols and The Jam. But who, nearly 40 years later, has the greater significance – John Lydon or Mick Fleetwood? Paul Weller or Stevie Nicks?

Naturally, it is possible to reply, with all sincerity, that Ms Nicks takes the pas or that Mr Fleetwood is a figure of titanic cultural import. As I say, we live in a relativist age and I wouldn’t dream of suggesting that a single snatch of The Jam’s “The Eton Rifles” has greater cultural value than the Mac’s entire recorded output. No, such judgements would only offend. One of the great merits of what, if it were an Agatha Christie novel, would be called The Mysterious Affair of the Popularity of E L James, is its reminder – a rather salutary reminder in many ways – that there are hundreds of thousands of people beyond the influence of the critical thought police, who don’t mind being thought dim, or culturally unattuned, or care what the pundits in the newspapers, and judge it to be worth reading; and that this, essentially, is how the phenomenon of the best-seller works.

The comforting thing about Grey, in fact, is how neatly it fits into an age-old tradition of the popular book, often promoted on the back of its salacity value (see Lolita, Lady Chatterley’s Lover, The Story of O, and so on) which some serious-minded people are uncomfortable about but which the public presses to its heart. One could even draw a parallel with Robert Montgomery’s epic poem The Omnipresence of the Deity (1828) whose awfulness was such that the great critic Thomas Babington Macaulay determined to destroy it with a broadside. The broadside was unleashed, and Montgomery duly extinguished, and yet the book, then in its 11th edition, went on until its 28th.

Why do people buy books? And why do they buy books by E L James? My own hunch is that, in the case of a work like Grey, myriad factors apply. Many of the buyers will be slapping their money down for the reason that led my outwardly strait-laced maternal grandfather to buy the original Penguin paperback of Lady Chatterley. A few desperate souls – and here I am coming over all judgemental again – may derive some pleasure from this po-faced chatter about bondage. And then there is the well-nigh morphic resonance that every so often propels a best-seller up the charts, to the point where potential purchasers barely know its name, only that it is a book they ought to be seen reading. I was working in a bookshop in the 1980s when a scholarly work named Montaillou by the French historian Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie which Penguin had reissued in paperback inexplicably began to shift copies. We sold 200 in a week, often to people who came in asking only for “the French book”.

Meanwhile, all those discomfited by Grey’s success can take solace in the fact that in 20 years’ time the whole phenomenon will be a footnote in book-trade history. As for the idea that complaining about a book which sells 647,000 copies is somehow “snobbish”, I can only refer you to my old tutor, the Oxford historian Sir Keith Thomas, who when it was suggested by an upstart pupil that such and such a statement was “a bit of a value judgement”, would only reply: “And we’re here to make them.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments