I recently travelled to interview political figures in the UAE and was surprised by what I found

Much of the time, news about Dubai and Abu Dhabi reports on human rights abuses, arcane laws and so on. But there’s another, progressive side to the UAE – and it feels like it’s going forwards at a time when my own country is going backwards

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The United Arab Emirates is going to Mars, seeking to rewrite cultural history, revolutionising robotics and redefining the conversations we have about governance and statecraft.

But why should you care?

My most recent journey to the Emirati sister cities of Abu Dhabi and Dubai gave me access to insights that I hope show you why it’s not just important but existentially vital to suspend cynicism and pay attention to their politics for a few moments.

The UAE is a young nation. In fact, it still has five years to go before it celebrates its golden jubilee. Yet in its 45 year history it has lost more than its fair share of diplomats and soldiers, often in the fight against extremist militants. In January, five Emirati diplomats were killed in a bomb blast while on a humanitarian mission in Afghanistan. The Emirati Ambassador, Juma Al Kaabi, sustained injuries and succumbed to his wounds a few weeks later. He was in Kandahar to lay the foundation stone for a UAE-funded orphanage.

Yousef Al Otaiba, a high-ranking UAE diplomat and current UAE Ambassador to the United States, summed up the national response of doubling down on cherished values rather than abandoning them when they are assaulted: “Will it affect our policy in Afghanistan? Will we reconsider sending humanitarian efforts? Of course not.”

The most telling response, though, came from Noura Al Kaabi, the UAE’s Minister of State for Federal National Council Affairs. When I expressed my dismay at the attacks, she simply said to me: "We're stronger."

In preparing to write this, I took the opportunity to ask Al Kaabi to expand on those words. “Take a look at Wahat al Karama,” she told me, referring to a memorial honouring the UAE’s war dead. “That monument pays tribute to the souls of our soldiers and diplomats who sacrificed their lives to protect our way of life... The memorial consists of panels, each leaning on the other... We all lean on one another just as we lean on our leaders and our leaders lean on us. That sense of community is what makes us stronger. That's why we give. When we are attacked, we reassert who we are more vigorously than before. We don't shy away from our values.”

There was a confidence Al-Kaabi’s answer that I yearn to see in the United States. It stood in perfect contrast to the national insecurity with which the US has consented to be terrorised even to the point that, if the rhetoric of the political powers that be are any indication, the country allows counter-terrorism to inform the tone of virtually every aspect of political discourse.

Speaking to me from Washington, James Zogby, president of the Arab American Institute, talked about the UAE’s approach of facing down an incendiary narrative by providing an alternative record to the march of extremism and closing up what seems to be spreading across the world from the United States and Europe to the Middle East and Asia.

“In the face of the instability that plagues many parts of the Arab world,” said Zogby, “the UAE represents a model of moderation, development, and tolerance. Cynics are dismissive, saying, ’It's because they have money.’ Wealth is a factor, but more to the point the UAE's success is due to wise leadership and sound values.”

The UAE was formed not by one leader but by a Supreme Council of multiple tribal elders representing seven different emirates. That propelled the country forward to a conglomerative form of government that honours the concept of shura (a form of tribal consultation) more organically than any other nation in the region. The legitimacy of Emirati leadership is inextricably connected to the institution of the majlis, literally a “sitting” in which citizens discuss their concerns with people in positions of leadership as well as one another. Every Emirati majlis I’ve ever attended has been remarkably collaborative and respectful.

That quality of empathetic attentiveness is also apparent in the halls of the Federal National Council. Witnessing the FNC in session, I saw a parliamentary debate marked by intelligent discourse and the grateful absence of political parties.

Each member operated with loyalty to their own ideas and to the constituents they were there to represent. The members were unhampered by allegiance to party and were unbeholden to the demands of political lobbies and special interest groups.

One moment that struck me was when Amal Al Qubaisi, the Speaker of the House, cited a perfectly respectable statistic regarding the performance of the country but, before going on to make her main point, punctuated her statistic with the words: “Of course we should be doing even better than this.” By taking off the shades of cynicism, we in the United States could stand to be reminded of the virtues of listening to one another and exercising national humility in our parliamentary politics.

When it comes to transparency in the press, the UAE has one of the most diverse media environments in the world (it hosts organisations like Two Four 54 and Dubai’s Media City) despite the widespread misperception that the Emirates remains a heavily censored state. I’ve written often for The National, a major newspaper based in Abu Dhabi, and I have never once been censored or felt the need to self-censor. Not a single time.

Too often, extremists on all continents are very quick to tell us what they avidly oppose and yet find it difficult to articulate what they are for. In contrast, the cultural atmosphere of UAE journalism requires the articulation of a thesis and a solution instead of indulgence in the politics of personal destruction.

I managed to sit down with the Editor-in-Chief of the National, Rashid al Murooshid, in Abu Dhabi where I asked him to sum up the goal of the paper. “We want,” he said “to show that with a responsible media organisation, no one should or need feel threatened by transparency, which in the end is in the national interest as we become a more developed economy. Indeed, the former is a prerequisite of the latter.”

Negative ratings, however, tell a different story. An article on press freedoms in the Emirates that appeared in The National itself back in 2015 ended with the following, slightly strange conclusion: “With journalists facing challenges in many countries, overall the press in the UAE is said by senior officials to have more freedom than legislation suggests.”

Similarly, in 2013, while indicating that new media legislation was in the pipeline, Sheikh Abdullah bin Zayed, the Minister of Foreign Affairs and then chairman of the National Media Council, suggested that a Freedom House ranking that placed the UAE 158th out of 196 countries in terms of press freedom was not an accurate reflection of reality. “This ranking is based on the law, not practice,” he said.

And that – the divergence between written, often antiquated laws on the one hand and reality on the other – sums up the reason for a healthy number of fatal misconceptions about the UAE. There is no doubt that it is up to the UAE itself to fix this issue by bringing all laws into synch with the open, free and vibrant reality of the society and nation as it exists in the real world.

So how does the UAE strategise for the future? Reem Al Hashimy, who led the UAE’s successful bid to host Expo 2020, spoke of the perils of overconfidence but offers a pragmatic alternate path. She speaks with precision and passion as she exalts the virtue of fact-based bidding and policy making. It was a world away from my experiences covering the personality-driven popularity contest that was the US election.

“I don't think we can succeed if we close up,” she said, on protectionism. “Our success model was built on embracing diversity and the aspirations of a largely younger population in this region.” She acknowledged that the UAE was an aspirational destination for many young people across the world, but was reticent about defining the UAE as a model of hope: “That’s a ‘title’ that they bestow upon us; we don't bestow it upon ourselves.”

Al Hashimy goes on to speak of the celebration of cultural expression as vital. She’s right to project a sense of urgency behind it. Music and the arts and poetry are essentially a training field for innovation and empathy. Cities like Dubai that contain an unrivalled multiplicity of nationalities turn into bloodbaths without the basic bedrock of empathy and respect that informs the culture and the tone.

On a broader global scare, we are, for the first time in human history, faced with a daunting prospect: anyone on the planet can digitally touch anybody else on the planet instantly. In this ecosystem, the sort of cultural interconnectivity that I saw at the Dubai Opera takes on a newly minted urgency.

Hoda Kanoo, the chairwoman of Abu Dhabi Music and Arts Festival, fended off naysayers over 25 years ago when they scoffed at the idea that this small and nascent Middle Eastern desert nation would ever need a prestigious concert music festival. She went on to build an organisation that is one of the largest performing arts presenters in the world today and she speaks with the passion and excitement of someone who sees a miraculous transformation around her and wants to share it with the world.

The UAE today is a nation that inhales far more than it exhales as people increasingly regard the country as a land of opportunity. And today, Kanoo speaks of a “rewriting of cultural history” with terrific conviction. The grandiosity of her vision is daunting.

Bill Bragin, artistic director of the Arts Center at NYU Abu Dhabi, is visibly animated as he shows me around the various theatres of the new cultural complex he sires. On Bragin’s team, I met people representing diverse walks of life, sexual orientations, religions and their director is passionate about them: “[They come from] extraordinarily different backgrounds… many coming to the UAE for the first time. They find it incredibly warm and welcoming to be here, and regularly remark on how open the community is here, which is often in contrast to their expectations based on what they read online.”

He refers to the coverage which usually surrounds the UAE in western media: human rights abuses, suggestions of dark conspiracies around oil and the notion that the UAE is a plastic society that imports brands like NYU, the Louvre, Guggenheim and so on without any interest in their cultural gifts but an eye on their wallets. On the last point, Bragin, who walks past the artworks of towering Emirati artists like Hassan Sharif, and Mohammed Kazem on his way to his office every day, balks.

But can the UAE itself help to correct the perceptions of itself that run rampant through the digital corridors of the internet? Revoking British-era sodomy laws or arcane vestiges that paint Emirati women as second class citizens (in fact, the statistics tell a story very similar to – and sometimes much better than – the West: Emirati women make up 25 per cent of cabinet-level ministers in the UAE , 50 per cent of employees in the space programme are women, and 46 per cent of the country’s graduates in STEM subjects are women) and replacing de facto extinct legal doctrine with explicit universal protections for all citizens would be a good start.

But the reality on the ground nevertheless remains the reality on the ground. “They realise,” continues Bragin, “that what's happening here is an amazing experiment in diversity, bringing people of so many different backgrounds together to build the country as a core strength. It's an optimistic, progressive vision of the future and of nation-building. And a strong contrast to the backwards looking false nostalgia which is infecting so many other parts of the world.”

While the UAE was developing and refining Masdar, a zero carbon city, America was having a debate on whether global warming was a Chinese hoax. When the Emirati citizen Ahmed al Menhali was beaten in Ohio for wearing UAE national dress, I was grateful to think that there were places like Dubai or Abu Dhabi where people wear whatever they want and don’t get oppressed for it, least of all by law enforcement agencies. From Mars missions to robotics and opera houses to the press, the UAE is quietly getting a lot of things right – despite what we might hear in some parts of the media. Perhaps Western nations should lend an ear and listen.

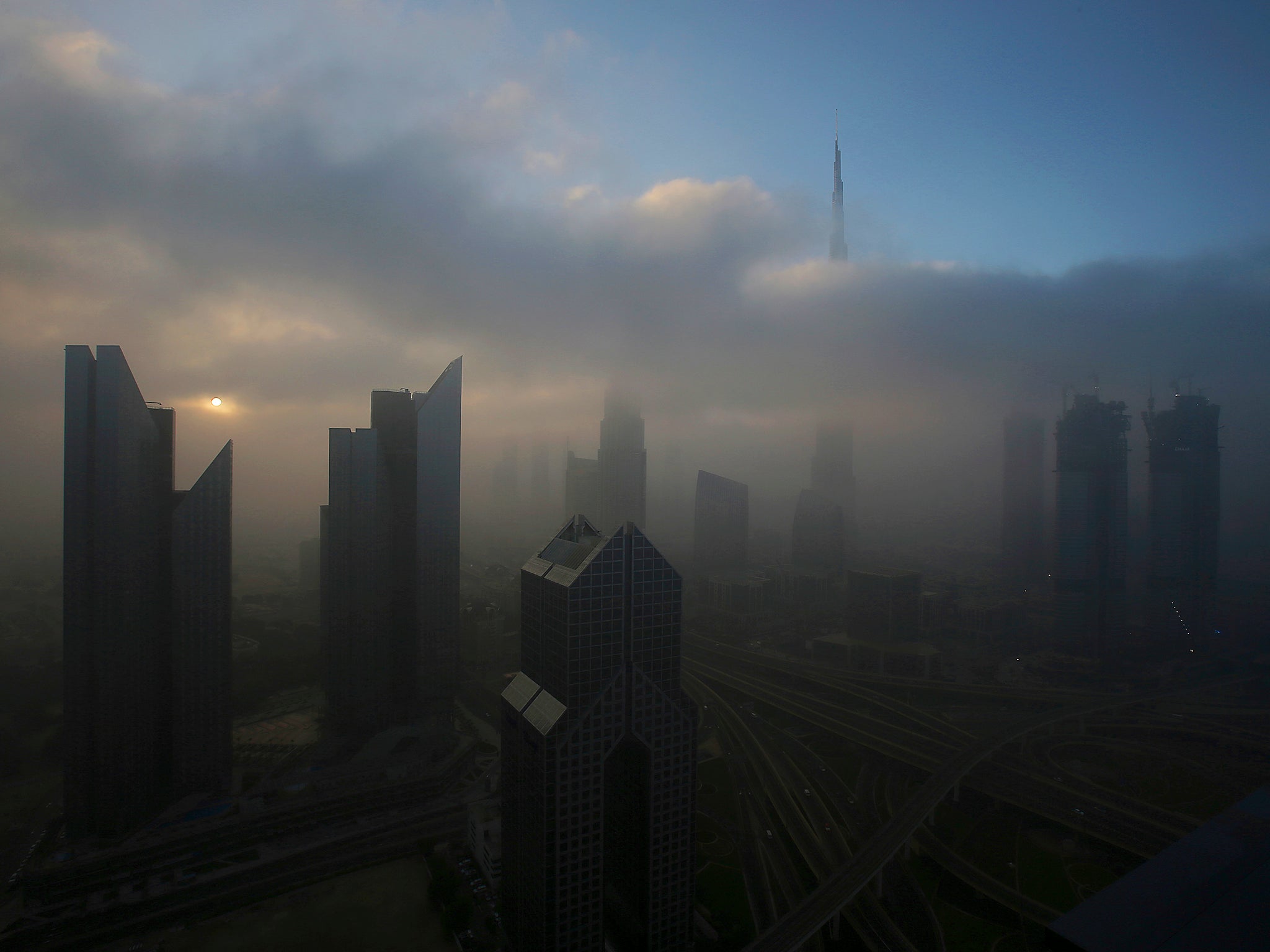

The tallest building in the world is in Dubai. The largest city on the planet is Shanghai. The biggest things are no longer in the West. But they can be. We just have to choose to be a part of the story of the future.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments