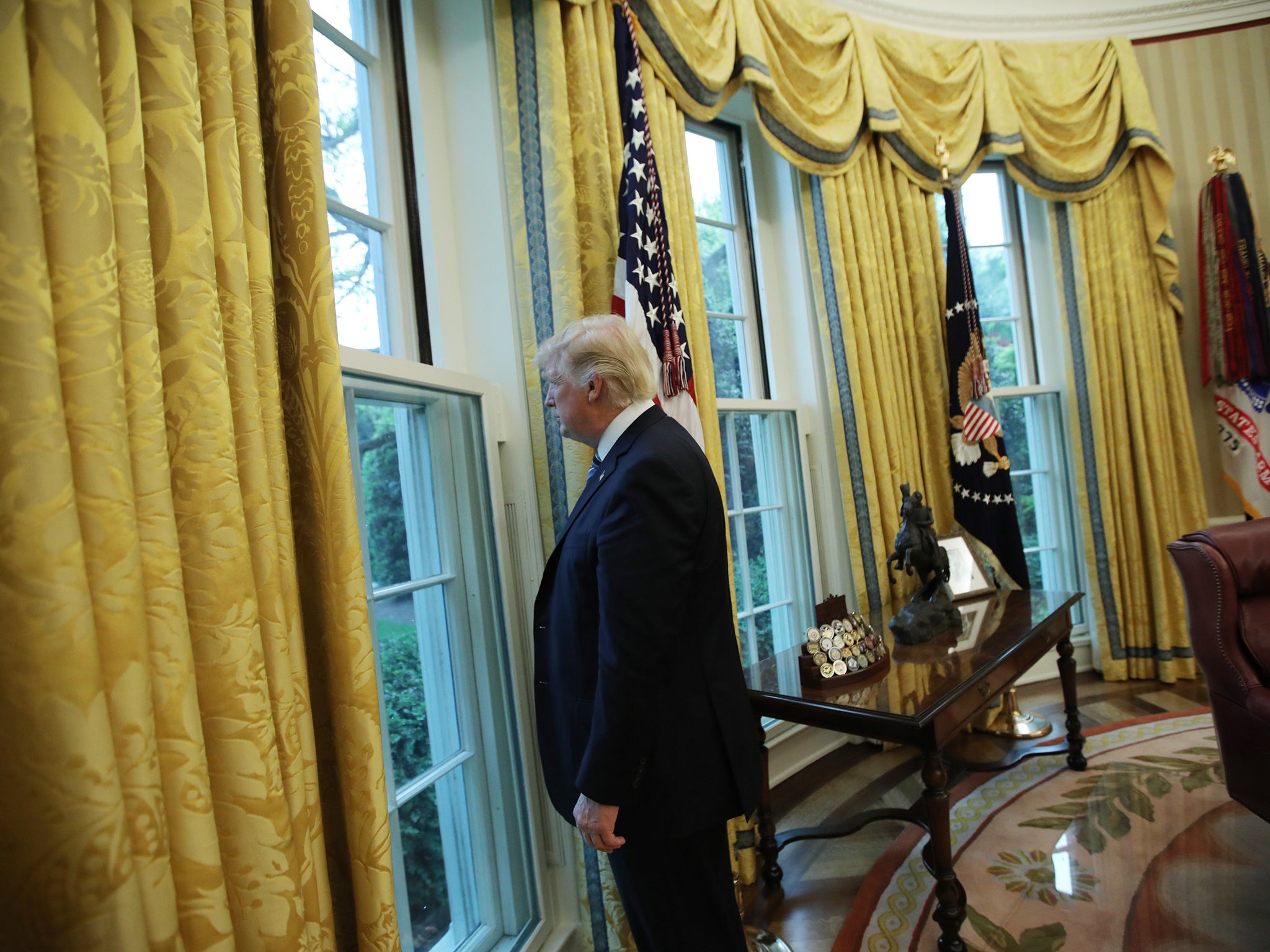

After his first 100 days in office, we should fear Trump more than ever

America's political, economic and ideological power is declining, so it's turning to military power to keep its world status

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Politicians and establishment media have greeted what they see as President Trump’s return to the norms of American foreign policy. They welcome the actual or threatened use of military force in Syria, Afghanistan and North Korea, and praise his appointment of a bevvy of generals to senior security posts. A striking feature of Trump’s first 100 days was the way in which the campaign to demonise him and his entourage as creatures of the Kremlin was suddenly switched off like a light as soon as he retreated from his earlier radicalism.

In reality, the Trump administration should be more feared as a danger to world peace at the end of his first 100 days in office than it was at the beginning. This is because Trump in the White House empowers many of those who, so far from being “a safe pair of hands”, have led the US into a series of disastrous wars in the Middle East in the post 9/11 era. There is no reason to think that they have changed their ways or learned from past mistakes.

This point is understood better in the Middle East than in it is in the US and Europe. In Baghdad, for instance, people are worried because they see the US building towards a renewed confrontation with Iran, possibly reneging on the nuclear agreement with Tehran and trying to curtail or eliminate Iranian influence in Iraq. Jim Mattis, the Secretary for Defence and former Marine general, and HR McMaster, the National Security Adviser and a general with combat experience in Iraq, are both volubly anti-Iranian. For soldiers like McMaster, the US failure in Iraq was unnecessary and self-inflicted and they intend to reverse it.

A US-Iran confrontation is bad news for Iraq because it may not mean an all-out war (though this is perfectly possible), but will be fought out on Iraqi territory by local proxies and allies. “Iraq really cannot take any more violence,” says one Iraqi commentator, “and there would be no clear winner.” He argues that the experience of the Iran-Iraq war of 1980-88, when the Iranians lost half a million dead, is seared into the minds of Iranian leaders and they will never permit a hostile foreign state like the US to become dominant in Iraq.

Many Western commentators were jubilant over Trump’s missile strike in Syria on 7 April, interpreting it as a return to a US policy that demands Assad’s departure as part of a peace deal. But this policy has long been dead in the water because Assad has no reason to go. Trump’s Syrian policy during the presidential election campaign always made more sense than that of Hillary Clinton as the voice of the US foreign policy establishment.

The great dilemma for ordinary Syrians and the Western powers is that if Assad goes or is weakened, then the main beneficiaries will be al-Qaeda and Isis. The choice is between very bad and even worse. There have been propaganda efforts to pretend that the Syrian armed opposition is not overwhelmingly led by Salafi-Jihadi groups. But these attempts are dying away as Jabhat al-Nusr, which is prone to name changes, mops up its last opponents in northern Syria.

An influential piece of propaganda has been to claim that the Syrian government is either complicit with Isis or not doing anything to fight them. But this is contradicted by a new analysis by the monitoring group IHS Markit, revealing that over the last year Isis has fought the Syrian government forces more than any other opponent. Between 1 April 2016 and 31 March 2017, 43 per cent of Isis fighting in Syria was directed against Assad forces, 17 per cent against the US backed but Kurdish dominated Syrian Democratic Forces and 40 per cent against other groups, most notably Turkish proxies reinforced by the Turkish army north of Aleppo.

“It is an inconvenient reality that any US action taken to weaken the Syrian government will inadvertently benefit the Islamic State and other Jihadi groups,” says Columb Strack, senior Middle East analyst at IHS Markit. “The Syrian government is essentially the anvil to the US-led coalition’s hammer. While the US-backed forces surround Raqqa, the Islamic State is engaged in intense fighting with the Syrian Government around Palmyra and in other parts of Homs and Deir al-Zour provinces.” If Isis was to capture Deir al-Zour, the largest city in eastern Syria, this would rejuvenate the group even if it loses Raqqa and Mosul.

The Trump administration says its priority is still to eliminate Isis and nobody openly disagrees with this. But the resurgent influence of the US foreign policy establishment along with that of Israel and the neo-cons, despite their dismal record in Iraq and Syria, is good news for Isis. Washington is seeking closer relations with Sunni states like Turkey and Saudi Arabia which have shadowy links to Salafi-jihadi groups and were at odds with President Obama.

People and policies gaining the power to make decisions in the Trump administration are the very same as those who helped turn the wider Middle East from Hindu Kush to the Sahara into an arena for endless wars. They have no idea how to end these conflicts and show little desire to do so.

There is a more general reason why Washington may in future be more inclined to employ the threat or use of military force to project its power. This is because its political, economic and ideological power is declining relative to the rest of the world. It was at its apogee between the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 and the financial crisis of 2007-8. The rise of China and the return of Russia as an international player cramps its ability to act unilaterally. The election of Trump is evidence of a deeply divided society.

As a military power the US can still claim predominance: international derision of Trump was instantly muted when he fired 59 Tomahawk missiles into Syria, dropped a big bomb in Afghanistan and claimed, falsely as it turns out, that a US armada was sailing towards North Korea. The lesson of recent US foreign interventions is that it is difficult to turn military power into political gains, but this does not mean that Washington will not try to do so.

Trump will have learned over the last month that minimal sabre rattling abroad produces major political dividends at home. Leaders down the ages have been tempted to stage a small short successful war to rally their country behind them. Frequently they have got this absolutely and self-destructively wrong and these wars have turned out to be large, long and unsuccessful.

Trump campaigned as an isolationist, which should protect him from foreign misadventures, but he has never had many isolationists around him. The architects of America’s failed military interventions since Afghanistan are still in business. Strip Trump of his isolationism and what you have left is largely jingoistic bravado and bragging about a return of American greatness. In future crises, both these impulses will make compromise more difficult and war more likely.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments