Michael Mansfield: Expensive, but justice must be done

The Bloody Sunday Inquiry would not have been necessary had Lord Widgery done his job - and the politicians not interfered

Last week when the Government announced a full public inquiry into the many deaths that had occurred at the Mid-Staffordshire Hospital, there were scenes of overwhelming joy and relief among the families and friends of those who died.

They had campaigned tirelessly for a simple and obvious objective – truth and accountability. The same is true of the families who pressed for the ongoing inquiry into the Iraq war; those who achieved an inquiry into the Marchioness disaster; and the family of Stephen Lawrence, who accomplished so much in yet another public inquiry. The list is endless and it exemplifies a crucial need in any civilised society. It is the need to know.

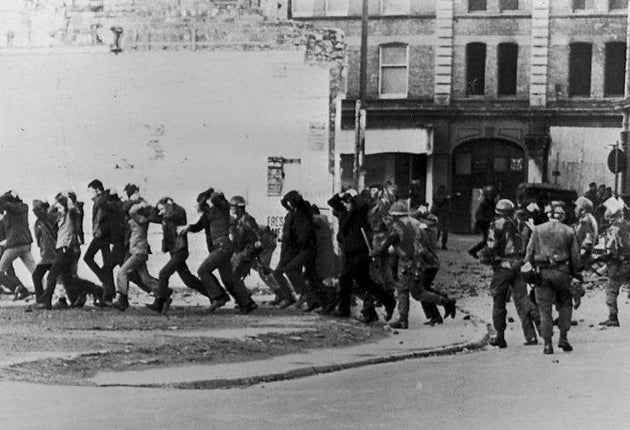

Sadly, over the past 25 years accountability and truth have been lacking in the political process such that a form of democratic bankruptcy has set in. One of the few ways in which the citizen has been able to bring authority to book has been by means of a public inquiry or, in some cases, an inquest. On Tuesday, the Bloody Sunday Inquiry report will be published. It should be remembered that, once again, it was the persistence and dignity of the families which brought this about.

The then Prime Minister, Tony Blair, stated this on 29 January 1998: "I am setting up the inquiry because the relatives of those that died that day have the right to expect us, their government, the British Government, to try to establish the truth of the events of that day. I am interested in their interests, their concerns and their sense of grievance, not in the sense of grievance of people who've engaged in terrorist acts."

At the same time, the Prime Minister added "that those shot should be regarded as innocent of any allegation that they were shot while handling firearms or explosives". This was echoed by William Hague, as the Tory leader, who repeated similar sentiments expressed by former Prime Minister John Major.

Bearing all this in mind, therefore, it was imperative that there should be, in the public interest, a full exploration of not just the circumstances of the shooting on the day, but also the background events which led to this situation. None of this would have been necessary if the first inquiry under Lord Widgery had done the job properly. It was rushed and superficial, completed within 11 weeks of the events. The testimony of the soldiers was not scrutinised thoroughly; statements collated by the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association involving hundreds of civilians were marginalised or not taken account of at all.

Most disturbingly, the Lord Chief Justice had a meeting with Prime Minister Edward Heath and the Lord Chancellor Lord Hailsham on 1 February 1972. This came to light on 4 August 1995 in a letter discovered in the Public Record Office. The Prime Minister had felt it appropriate to remind the Lord Chief Justice "that we were in Northern Ireland fighting not only a military war but the propaganda war".

This goes some way to explaining why the second inquiry has taken so long and incurred extensive costs; it has had to make up for the deficiencies of the first. Lord Saville and the panel members, as well as the legal team that acted as counsel to the inquiry, took meticulous care, courtesy and patience to ensure no stone was left unturned. This was a unique exercise because of the ambit of background factors. What erupted on Bloody Sunday did not come out of the blue.

There was a long history of economic and political deprivation combined with the exigencies of military occupation. This provided a matrix of complex pressures, all of which required reappraisal. Part of the object of an inquiry is to learn lessons in the hope that history may not repeat itself. That has certainly been at the heart of the ones mentioned above.

There is a further particular reason, peculiar to this inquiry, which also contributes to its unique nature. It is the peace process itself. The inquiry was announced in January 1998 only months before the Good Friday Agreement. There can be little doubt that this was another part of the jigsaw building a picture of peace. As Martin Luther King repeatedly observed, "There can be no peace without justice." And I would merely add that there can be no justice without truth. It is important to note that the final piece in the jigsaw, namely the transfer of justice and police powers, occurred just before Easter this year.

For the main parties, the families, who in a sense are representing the public interest, it has been a harrowing experience. It was their moment to speak in a way they had not been allowed to before. It was their moment once and for all to put the record straight and restore innocent reputations. It was their moment to have questions asked about how this could have been allowed to happen, who was responsible, who were the central decision-makers. This is accountability in action which is rarely witnessed in other arenas. Above all, it permits them to begin an unremitting process of coming to terms with it all. These are the sentiments expressed by many of those who participated in the Truth and Reconciliation Commission held in South Africa, led by Desmond Tutu. It takes time and it takes money, neither of which can properly reflect the benefits for us all of constructing a foundation for coexistence. This can provide an example for other parts of the world where intransigence and bigotry dominate.

Michael Mansfield QC represented three families at the Bloody Sunday Inquiry. The case is analysed in his Memoirs of a Radical Lawyer, published last year

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies