Robert Fisk: Truth and reconciliation? It won't happen in Syria

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.If you want to understand the cruel tragedy of Syria, there are two books you must read: Nikolaos van Dam's The Struggle for Power in Syria and, of course, Patrick Seale's biography Assad.

Van Dam was an ambassador in Damascus and his study of the Baath party was so accurate – albeit deeply critical – that all party members in Syria were urged to read it. But this week, for the first time, Lebanese journalist Ziad Majed brought together three of Syria's finest academics-in-exile to discuss the uprising in their native country, and their insight is as frightening as it is undoubtedly true.

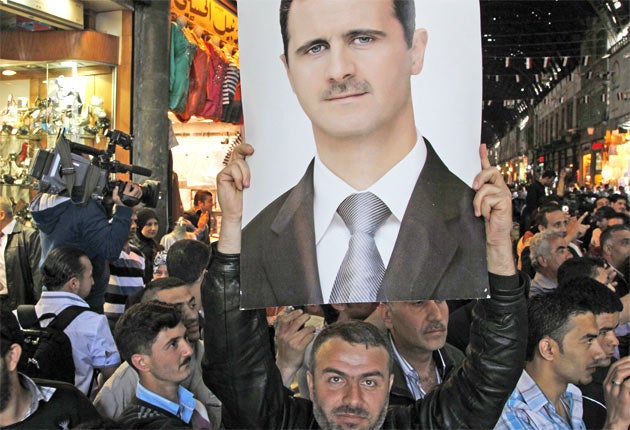

According to historian Farouk Mardam-Bey, for example, Syria is "a tribal regime, which by being a kind of mafia clan and by exercising the cult of personality, can be compared to the Libyan regime", which can never reform itself because reform will bring about the collapse of the Baath party which will always ferociously defend itself. "It has placed itself – politically and juridically – upon a war footing," Mardam-Bey says of its struggle with Israel, "without the slightest intention of actually going to war."

Burhan Ghalioun makes the point that "the existence of the regime is like an invasion of the state, a colonisation of society" where "hundreds of intellectuals are forbidden to travel, 150,000 have gone into exile and 17,000 have either disappeared or been imprisoned for expressing their opinion... It is impossible (for President Bashar al-Assad) to say (like Mubarak and Ben Ali) 'I will not prolong or renew my mandate' like other presidents have pretended to do – because Syria is, for Assad, his private family property, the word 'country' is not part of the vocabulary."

Assad has opened Koranic schools and "Bashar's recent proposal to create a religious Islamist satellite television channel as a 'gift' to Sheikh Mohamed Said Ramadan Buti (who supports the regime) shows very clearly his support for an obscurantist Islam which is loyal to the regime" as part of a plan, according to Ghalioun, since "the regime is gambling on sectarian discord to raise the spectre of war and chaos if the protests continue". In Aleppo and Damascus, Mardam-Bey insists very convincingly, the Assad regime wants to persuade the large Christian communities that "if the regime falls, it will be replaced by an extremist Islamist regime and that their fate will be the same as that as the Christians of Iraq".

In holding on to power, literary critic Subhi Hadidi said rather archly, the Assad regime has divided Syrians into three categories: "The first belongs to those who are too preoccupied in earning their daily bread to involve themselves in any political activity. The second group are the greedy whose loyalty is easy to buy and who can be brought on board and corrupted in a huge network of 'clientelism'. The third are intellectuals and activist opponents of the regime who are regarded as 'imbeciles who believe in principles'."

Yet none of these men reflect upon the frightfulness of the killings in Syria and the immense difficulties of reuniting a post-Assad country after civil war. By chance, the anniversary of the start of Lebanon's own 15-year civil war, which killed up to 200,000 people, was marked last month with an Amnesty report which estimated that 17,000 men, women and children had simply disappeared in the conflict, recalling repeated promises by the post-war Lebanese authorities to investigate their fate, none of which were honoured.

A 1991 Lebanese police report did in fact give an exact figure for those who must surely be in their graves – 17,415 – but this has been disputed. Most of these people were kidnapped by Muslim and Christian militias, but some families have related how their relatives were taken by Israeli soldiers in 1982 and by armed men who transferred them to Syria, never to be seen again. This was the Syria of Bashar's father Hafez, and Bashar did himself permit the setting up of a joint Lebanese-Syrian committee in 2005 to investigate what happened to those Lebanese who were abducted to Damascus. It has met 30 times. Needless to say, its conclusions – if any – have never been made public.

Even today, in the centre of Beirut, relatives of the disappeared camp out next to photographs of sons and husbands and fathers who vanished more than 35 years ago, clinging to a frayed thread of hope, permanent victims of the civil war. Neil Sammonds, who conducted the research for Amnesty, told me Lebanon "doesn't carry out its obligations properly and it hasn't done for years. The judicial authorities are unable or unwilling to do their job. Only when they do will we be able to find out the truth".

But I fear they never will do their job. Opening mass graves in a sectarian society is a very dangerous act – the Yugoslavs did this in a search for Second World War massacre victims, and within months the Balkan wars flamed back into life with mass killing, concentration camp atrocities and ethnic cleansing. Truth and reconciliation committees do not exist in Lebanon – nor will they, I fear, in Syria – and 20 years after the Lebanese authorities agreed to produce a national school history book to include the civil war, it does not exist. An extraordinary 67 per cent of Lebanese students go to private schools (D Cameron, please note), yet they prefer to teach "safe history" like the French revolution. If Lebanese children want to read of their fathers' and mothers' 1975-1990 golgotha, they often have to buy British and French books about the civil war.

The Syrian academics also warned that Syria's conflict could cross into northern Lebanon where Sunnis live next to Alawites, the Shia sect to which the Assads belong. Touring northern Lebanon this week, I saw posters outside Sunni Muslim homes, saying "Assad – you won't escape us". Not something their Alawite neighbours are likely to enjoy reading. But I will end by returning to a bloody if ultimately hopeful prediction of Subhi Hadidi. " The oppression of the (Assad) regime will be terrible. But the courage of the people in the street and the overall struggle – despite the difficulties they encounter – along with the very youth of the protesters, will lead the Syrian people to follow them all the way to freedom."

I'm not so sure. In the wreckage of post-Assad Syria – if this time come to pass – it will be difficult to reunite Syrians amid the dried blood of their mass graves. Try writing their new history books for them.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments