Robert Fisk: The forgotten martyrdom of Algeria's reporters

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.How quickly we forget the murder of colleagues.

The Algerian press, freer than it has been for years (though that's not saying a lot), now boasts a smart and cynical edge. The Arabic-language Al-Sharq newspaper, with a million copies sold a day, rightly claims the highest circulation in the Arab world. But then there I was, sitting above Bab el-Oued in the winter sunshine, flicking through the pages of Le Soir d'Algérie, when a face glares at me from a book review. Thick-haired, moustache creeping round his cheeks, giant 1990s spectacles, sharp eyes, the features of journalist Tahar Djaout, subject of a new biography by Algerian writer Rachid Mokhtari. Djaout died 2 June 1993. Murdered, of course. Like 94 of his fellow journalists. Ninety-four!

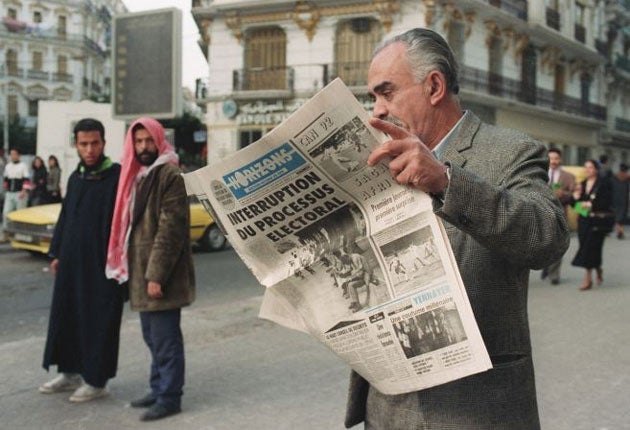

A few years ago, I wouldn't have been sitting here above the Algiers Casbah. A French colleague of mine was murdered less than a mile away on 1 February 1994. In those days, four minutes was all we allowed ourselves in shops – five gave the watchers enough time to call the killers of the Islamic Armed Group – and lingering on the streets to read a newspaper was suicidal. But we could retreat at day's end to the few heavily guarded hotels in this beautiful, morally damaged city. Algiers is safer now. But Tahar Djaout's face brings it all back.

He put his arms round his three daughters on his fatal day, said goodbye to his wife, walked to the street from his fourth-floor apartment, "lost in his thoughts" over the next edition of his paper Ruptures, as a colleague put it later, failing to notice one of three men climbing from a car. The moment he caught sight of the gun, Djaout must have realised he was too late. Three bullets, one in the head, and he collapsed to the ground in a coma. His latest column had appeared that very morning on the Algiers news-stands, a condemnation of the attempted assassination of Omar Belhouchet, the editor of El Watan and a friend of mine. It took Djaout eight days to die.

A few of the almost 100 murdered journalists in Algeria are thought to be the victims of government thugs. But most were undoubtedly slaughtered by the Islamists, not because they were pro-Pouvoir – a lot had been harassed, arrested or detained by the police – but because they did not want to live in the Islamic republic which seemed certain to emerge in Algeria until the regime stopped the second round of elections (to the quiet applause, of course, of America, France and most of the other Western nations who spend their time promoting "democracy" around the Muslim world). The armed groups had even given journalists a warning, a few days' grace to put their pens away, or else.

A sober, black-covered book by journalist Lazhari Labter now records the martyrdom of the reporters of Algeria. It makes terrible reading – not least because we have, all of us outside, forgotten these literal pages of suffering. I reported many of their deaths and I had forgotten them. Youcef Sebti, a bachelor in his fifties, a man deeply learned in Arab and French culture, poet, humanist, nationalist, intellectual; just before midnight, 27 December 1993, three armed men entered his apartment in the Algiers suburb of El Harrach. Sebti's housekeeper found his body in a pool of blood next morning, slumped beneath a framed copy of the executions in Goya's The Third of May, 1808.

Said Mekbel was shot twice in the head on 3 December 1994, as he took his lunch in an Algiers restaurant. They found him sitting at his table, dead, knife and fork still in his hands. Mekbel – perhaps the most popular journalist in the country – ran a wonderful column called "Mesmar J'ha" – "The Rusty Nail" – in which he had written of his work as a journalist. "This thief who slinks along walls in the night to go home, he's the one. This father who warns his children not to talk about the wicked job he does, he's the one... He's the one whose hands know no other skill... He is all of these, and a journalist only." In his office, he left an unfinished article in which he wrote: "I would really like to know who is going to kill me."

Then there was Khadija Dahmani. Twenty-seven years old, she told colleagues that only by working as a journalist could she liberate herself from being cloistered at home as a Muslim woman. "The only way in which she could be free was through her work," a fellow journalist wrote. She was intercepted by armed men just outside her home on 5 December 1995, and shot dead. How do you recognise an Algerian journalist, the cartoonist Dilem asked? "He's the only guy who has a pen in his hand, two dinars in his pocket and three bullets in the head." In El Watan, Boubakeur Hamidechi condemned those reporters who always tried to find a reason for each killing. "Every time a journalist is targeted, the sincerest pens try to explain it," he wrote. "In a way, we work on the logic of proof, something which makes sense of an act of terrorism."

Yes, today may all of us beware... Zouaoui Benamadi, the editor of Algérie Actualité – he survived the war – once explained to me: "Only Islamic movements are capable of breaking the government systems that exist in the Arab world. But who are these people? What are these strange clothes they wear? They have beards and wear white caps and shortened trousers to show their allegiance... But we have beautiful national clothes in Algeria. We have the burnous, a big woollen robe. Where does it come from, this curious dress of theirs?" Well, Saudi Arabia, you might have said. But Afghanistan is where many of the men came from. They were Algerians who fought alongside Osama bin Laden against the Soviet army, another little blowback that soaked Algeria deeper in blood than Afghanistan.

And now, when we drench our pages in sorrow at the death of every Western reporter, why don't we remember these 94 Algerian men and women? Yasmina Drissi, an editor on Le Soir d'Algérie, had her throat cut open in September 1994, after being kidnapped while waiting at a petrol station. Rachida Hammadi, a television station secretary, was shot in the head on 20 March 1995, her sister Houria killed as she tried to protect her. Rachida died a few hours later. Do these poor souls not touch us? And if not, why not? Because they were Arabs? Because they were Muslims, because they were darker skinned than us, had brown rather than blue eyes, spoke French rather than English when they chose not to speak Arabic, because they were – let us speak frankly – Algerians? I fear that all this is true. I wrote about them at the time. And then, until a few days ago – until Tahar Djaout's face stared at me from a newspaper above the Casbah of Algiers – I forgot them too.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments