DJ Taylor: For 168 years News of the World was as English as roast beef

It could be amused by sexual peccadilloes one week and puritanically disapproving the next

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.For evidence of the News of the World's absolute centrality to a certain part of our national culture in the past century and a half, one need only turn to the opening paragraph of George Orwell's 1946 essay, "Decline of the English Murder": "It is Sunday afternoon, preferably before the war. The wife is already asleep in the armchair, and the children have been sent out for a nice long walk. You put your feet up on the sofa, settle your spectacles on your nose and open the News of the World..."

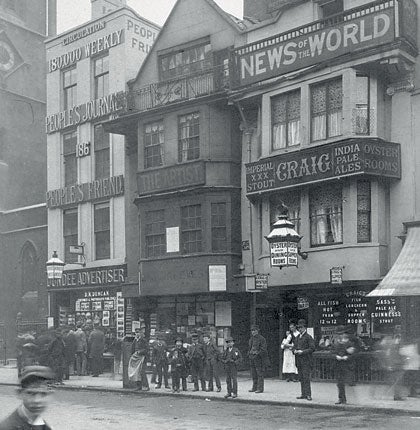

The essay is about changing attitudes to crime, and what might be called the moral basis of criminality, but it is also an evocation of early 20th-century British working-class life – the smell of roast beef and suet pudding, pipe smoke rising above the open fire – and at its heart, significantly enough, lies a single mass-market newspaper. Orwell's locus classicus is the 1930s, but the portrait could date from any time in the previous 90 years. Founded in 1843, aimed at a newly literate working-class and lower-middle-class audience and competitively priced (3d even in the age of newspaper stamp duty), the News of the World, even in its early days, got by on the source material of the penny dreadful – murder, sexual indiscretion, salacious court-reporting and the ever-enticing world of "crim con" (ie "criminal conversation", that is adultery.) Even in the early post-war era, before the collapse of censorship and the age of sexual liberation, the NOTW kept up the salacity count by offering sexual assault-trial transcripts ("What was the defendant's next action, Miss X?" "He asked me to remove my knickers, Your Honour" etc.)

However grandly sustained by an eternal cast of randy vicars, misbehaving politicians and adulterous celebrities, not to mention an abiding fondness for tall stories – a famous standby in the 1920s was the story of a man swallowed by a whale and supposedly coughed up three days later, still alive but bleached white by its gastric juices – the NOTW's moral atmosphere was seldom quite as clear-cut as it seemed. It was vulgar, but except in very exceptional cases not obscene. It could be amused by sexual peccadilloes one week and then puritanically disapproving of them a week later. Philistine, anti-art and incorrigibly vindictive, it also cultivated a terrific vein of sentimentality born of a weakness for "old folks" and "kids". It was for "us" (never exactly defined) against "them", without ever trumpeting the fact they "they" owned it and that if anyone could be said to be exploiting working-class sensibilities throughout the post-war era it was the magnates of Bouverie Street, the paper's HQ until the final late 1980s transit to Wapping. (Rupert Murdoch bought the company in 1969.)

Its general atmosphere, at least until the late 1980s when competition from sewer-level scandal sheets like the Sunday Sport made the material even less appetising, was, approximately, that of a variety hall which is awaiting the arrival of Max Miller in the knowledge that the censor has gone to sleep in the front row. It was at all times sensitive to the interests of its readers, often in what were on the face it rather bizarre ways: I can remember my astonishment, as a teenager, finding a leading article in it lamenting the death of the best-selling novelist A J Cronin with the bluff sign-off "Thanks, mate". But Cronin was exactly the kind of writer the NOTW's millions of readers would have heard of and enjoyed.

And what was yours truly doing reading this benighted scandal sheet in late 1970s teendom? The answer is that the NOTW was another kind of cultural signifier, capable of defining the class origins and affiliations of the people who read it almost from one page to the next. My mother, the middle-class daughter of an insurance manager, groaned if it so much as entered the house. My father, on the other hand, an escapee from the council estates, liked the occasional prurient glance at its contents in the same spirit that he brought to Carry On... films or The Benny Hill Show.

"Every morning a piece of the world comes through the door... But remember it's just a comic, not much more" runs that fizzing late 1970s single from The Jam, "News of the World". Quite right, too. And yet even a comic populated by an adult cast of brothel madams, serial love-rats and celebrity reality-evaders, can be an uncannily accurate reflection of the kind of myths, illusions and idées fixes by which a nation buttresses its sense of collective identity. All this makes its passing a horribly symbolic moment, both for the history of newspapers and society itself.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments