What did Grimsby do to deserve Sacha Baron Cohen?

The creative elite has allegedly turned with vicious malice on the very people whom their artistic forefathers used to hail as decent and dauntless

What’s not to love about this breezy seaside town? A writer of French origin who grew up nearby remembered it this way: “As I lay dreaming in my bed/ Across the great divide/ I thought I heard the trawler boats/ Returning on the tide/ And in this vision of my home/ The shingle beach did ring/ I saw the lights along the pier/ That made my senses sing.” Ah, bless. This favoured spot has stirring mythology to spare as well. Once upon a time, a mighty god disguised as a fisherman raised an orphan here, a boy-hero destined to rule great kingdoms on both sides of the seas. I speak, of course, of Grimsby.

Pop pedants may object that when local boy Bernie Taupin wrote the lyrics for “Grimsby”, from Elton’s John’s 1974 album Caribou, he was gently extracting the old Mickey Bliss. So what? Sarcasm lies strictly in the eye of the beholder. Besides, no one would dare to challenge the role of Odin, all-father of the gods who roamed the earth under the soubriquet of “Grim”, as legendary founder of the North Sea port. But the ancient town of fish has seen its trawler fleet shrink during the container age from 400 to a bare handful of ships, even if it still processes and packs the harvest of the sea by the hundreds of tons.

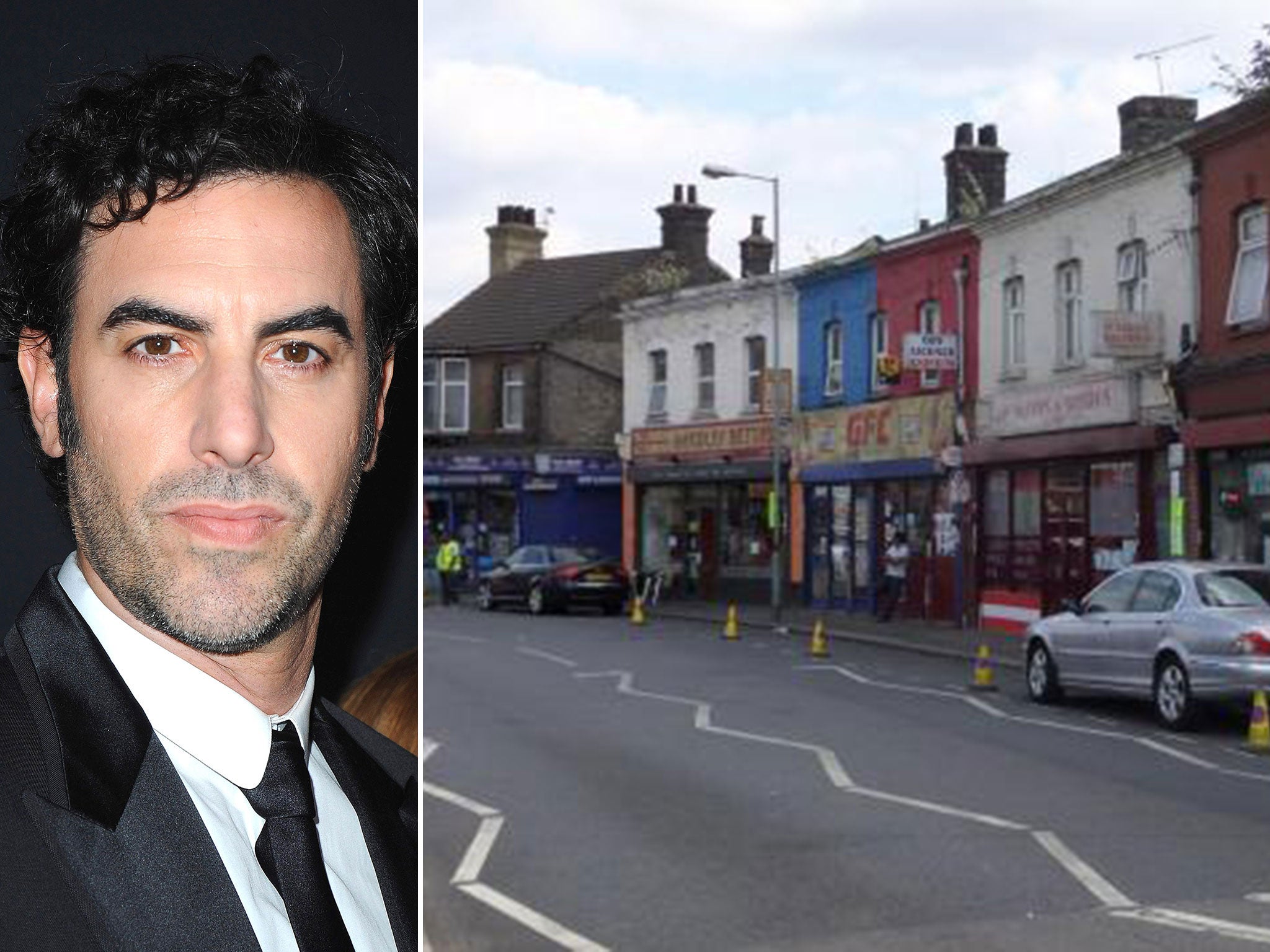

Now, to add insult to maritime injury, Sacha Baron Cohen has chosen not merely to set his new film in a dilapidated English hell-hole of the 1980s but to call it Grimsby. Not content with upsetting one sea-facing borough around the North Sea coast, the creator of Ali G, Bruno and Borat has been filming in distant Tilbury this week. Scenes of gross obesity, daytime inebriation, teenage misconduct and public urination have duly managed to offend estuarine Essex as well as wind-scoured Humberside. This year, Grimsby has already had to mobilise to fight off the attentions of Channel 4’s poverty-porn series Skint.

Myself, I blame the Vikings – or rather, the snooty Anglo-Saxon elite’s disdain for them. How come that so many British satires and exposés of “underclass” depravity happen to be set along the eastern seaboard, from the Thames estuary through Essex and littoral East Anglia, into Lincolnshire and Yorkshire and up to Tees and Tyne? Supposedly rough and boozy Scandinavian invaders left a strong genetic footprint all along that coast. Some people will counter with Vicky Pollard – the shambolic pink-clad “chav” from Matt Lucas and David Walliams’s Little Britain, and a certified Bristolian from her vowels to her venues. But then those marauding Norsemen raided up the Severn as well as up the Ouse.

In Tilbury or Tewkesbury, Grimsby or Guildford – should we care? Through one fretful lens, Baron Cohen’s targeting of yet another rundown town for ridicule will feel like a new front in the long ideological war directed at the remnants of the “white working class”. In this perspective, British culture since the time of Thatcher has ruthlessly rebranded the salt of the earth as the scum of the earth. From the films of Mike Leigh (Meantime to All or Nothing) to the television drama of Paul Abbott (Shameless), by way of Little Britain and Benefits Street, the creative elite has allegedly turned with vicious malice on the very people whom their artistic forefathers used to hail as cheerful, decent and dauntless Tommies, miners, dockers, drivers, sailors and millhands.

In 2011, Owen Jones’s polemic Chavs gave an angrily eloquent voice to this sense of betrayal. Unless sweetened by the multicultural sauce that now makes it palatable to the liberal bourgeoisie, working-class (often, no-longer-working-class) life strikes our genteel glitterati as nasty, British and short. This horror hardly counts as national self-hatred since the supposed oafs and yobs singled out for disgusted caricature indelibly belong with Them rather than Us. In a shrewd review of Chavs for this newspaper, Labour’s policy-review chief Jon Cruddas MP connected this renewed panic over the idle lumpenproletariat to a return of the Victorian distinction between the “deserving” and “undeserving” poor. A century ago, the Fabian pioneers had sought to sweep that away.

Now, the argument runs, our creative industries conspire to rob the working-class losers from a globalised age of honour as well as livelihood. Baron Cohen most probably picked Tilbury as his location for its humdrum municipal ordinariness. Still, it’s poignant to reflect that the Thames port has, in the arrival of the Empire Windrush from the Caribbean in 1948 or the departure of “Ten Pound Poms” on their assisted passages to Australia in the 1960s, witnessed at first hand the shifting tides of change. Who will ever film its real history?

As the comic trapdoors of Ali G or Borat prove, Baron Cohen loves to mine the ground beneath our feet. I would be surprised, and pretty disappointed, if the Eighties spy-meets-hooligan plot of Grimsby does no more than echo the chav-baiting of more mediocre comics. More widely, this genre tends to disclose the underlying attitudes of its public. Mike Leigh and Paul Abbott stress that they love and admire the people whom critics accuse them of mocking. Yet they can never micro-manage the response. I have watched Leigh films with audiences for whom the tenderly excruciating comedy of manners and status in High Hopes or Life Is Sweet offered, mostly, a good laugh at the oiks.

In any case, the peculiarly English form that you could dub Plebeian Grotesque has deep roots in art as well as life. Who first took down the witless chavs? Step forward, William Shakespeare. In Henry VI Part 2, the young playwright stages Jack Cade’s Kentish uprising of 1450. Cade the rebel leader is a boorish twit who, when he confronts ruling-class Sir Humphrey (yes, really), thinks that speaking French makes you a traitor. Plus ça change. He finds it “monstrous” that anyone should know how to read and write. True, Shakespeare’s loathing for the dumb rebel turns on his hypocrisy – Jack wants to be king himself – but he hardly gives “the filth and scum of Kent” a fair hearing in their xenophobic resentment. These days, Jack could expect a regular gig on Question Time.

From the engravings of Hogarth to the novels of Dickens, the Great English Lout belches and staggers his way from century to century. Treat Martin Amis’s anti-hero Lionel Asbo – the small-time thug from outer-suburban “Diston” whose lottery ticket nets him £139,999,999.50 – as a homage to this icon as much as a satire on celebrity idiocy. When, last year, I talked to Amis about his novel, he both emphasised its Dickensian debts and explained why that tone sidesteps naturalism. “It’s not mimetic social realism; it’s something else. It’s more like melodrama or burlesque. Cause and effect is a bit hazier. There are certain transformations, rewards and punishments. It’s an inordinate form.”

Our Plebeian Grotesque doesn’t really purport to tell a sociologically watertight truth about a Grimsby or a Gravesend. But that might not give comfort to the aggrieved burghers of the latest “crap town” in the line of a satirist’s fire. Neither does the “inordinate” form always shake off the taint of simple snobbery. A certain strain of middle-class cosmopolitanism has lent that snobbery a mask and alibi. By now, I have read quite enough state-of-the-nation novels in which some noble eastern European migrant has to navigate his way through the woeful ignorance and drunken vulgarity of England’s perpetually puking proles. As if no one east of the Oder had ever downed a dram.

Along with a default setting to cartoonish satire goes its twin, a downbeat home-grown miserabilism. Here, sink-estate high-rises or threadbare edge-of-town developments will host a depressive cast of junkies, thieves, drifters and abused kids. Although J K Rowling cleverly invoked but then tweaked this genre for her grown-up novel The Casual Vacancy, it thrives mostly in the cinema, from Ken Loach to Andrea Arnold (whose Fish Tank was shot around Tilbury). Again, the makers will avow their deep respect for the characters. Not every viewer will agree. Meanwhile, one vainly hopes for a few well-observed, non-traumatic, non-dysfunctional stories about everyday English life of the kind that routinely emerge (say) from the French domestic film industry. Is that too much to ask?

Whether told in a farcical or mournful light, these flesh-creeping tales of underclass squalor should be coming to the end of their mattress-strewn, cider-sluiced, pitbull-infested road. They have hardened into a package of conventions as rigid in their own way as the world of Downton Abbey. Hence, perhaps, Baron Cohen’s period setting in the hooligan heyday of 30 years ago.

Grimsby will survive Grimsby (as will Tilbury). And if those towns and some others fear that smug metropolitan storytellers will always put the boot in, remember that any serious bruises that they sport come not from scoffing snobs but from the death of trade, the flight of wealth, the loss of jobs. Resolve those core problems and Sacha Baron Cohen’s pursuit of yobbish stereotypes on the coast will hurt them no more than Made in Chelsea can dent property prices in SW3. By the way, the priciest five-bedroom house currently on sale in Grimsby will cost you £399,000; in Chelsea, £12,500,000. It’s an ill (east) wind…

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments