We’d moved on from New Labour long before David Miliband said he was going

David was a great boss for the 10 very enjoyable minutes that I was a minister at the Foreign Office

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.I’m constantly amazed at how little magnanimity there is in politics, as was shown by the reaction to David Miliband’s standing down.

So many snide, nasty and vindictive comments filled my timeline that I abandoned Twitter for 24 hours. And when I returned, it was full of Tories crowing that “this is the end of New Labour”. Well, yes, folks. Tell it not in Gath, publish it not in the streets of Ashkelon, but not even New Labour was going to live for ever. Few now doubt that Labour had to shake off its donkey jacket reputation for believing six impossible things before breakfast in the 1980s. We had tried to put our 1983 manifesto convincingly behind us, but even up against John Major in 1992 we never quite managed to convince the public that we were not crazed ideologues. So New Labour’s ideological clean slate was necessary. Its core tenet, that you had to marry conviction to practicality – “traditional values in a modern setting”, as John Prescott would put it – was right. And its determination to seek and hold the centre ground was both morally sound and electorally successful.

But that was then, and no sane general continues fighting last year’s battles all over again. The centre ground of politics is not now where it was. Virtually every aspect of modern politics has to be seen in a new frame. The evident fragility of the worldwide finance system has radically altered everyone’s perspective. Gone are the days of parties competing to create ever lighter-touch regulation. Economic stagnation and straitened national finances have changed the nature of the political debate about fair taxation and allocation of resources. The ever faster flows of international capital have both reinforced the sense of our global interconnectedness and people’s desire to create national safe harbours.

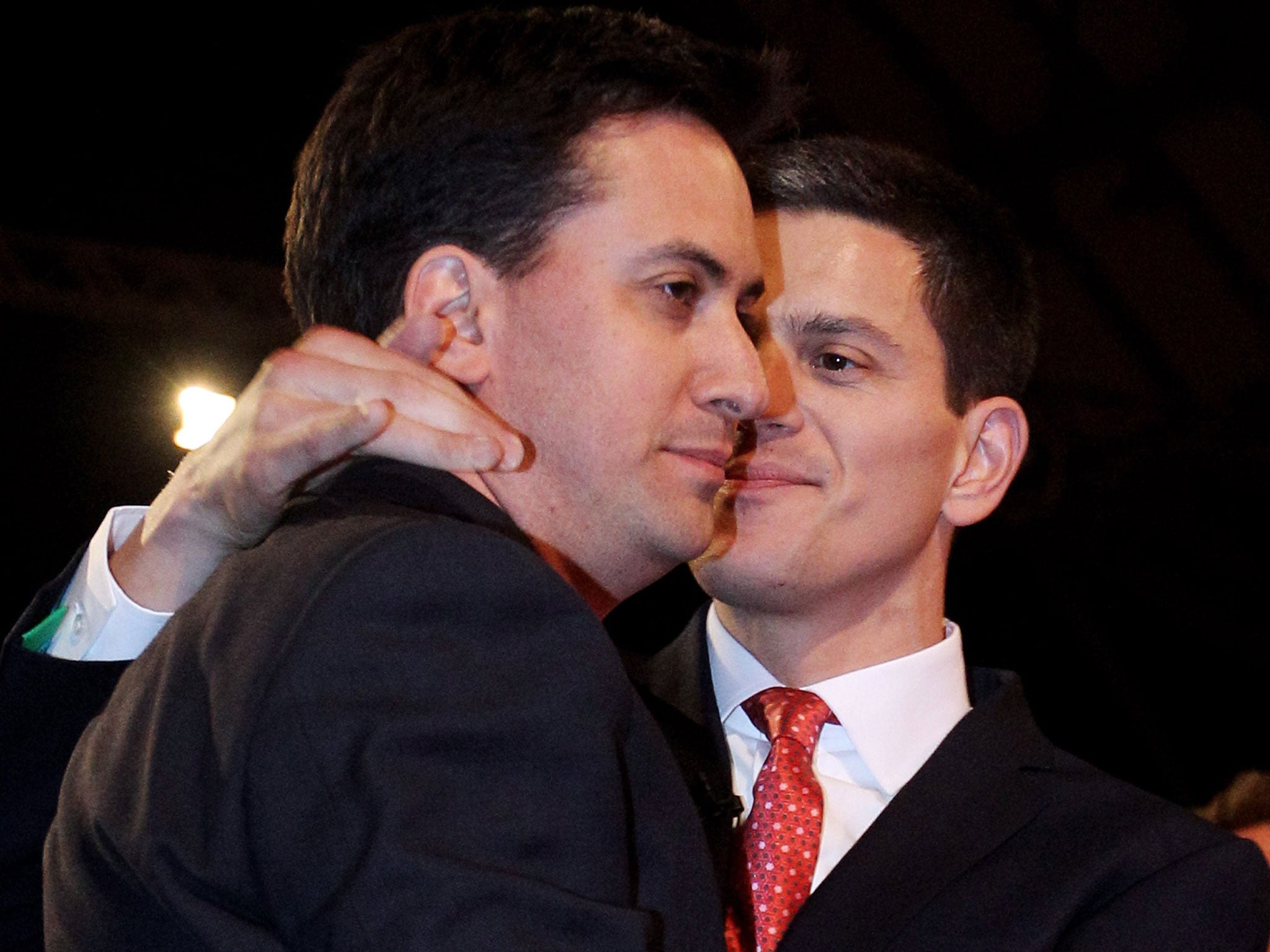

One element of New Labour that still chimes is the need to reassess the lie of the centre ground in every political generation. After all, what might have seemed extreme a decade ago has become commonly accepted. The “loony left” was excoriated for espousing homosexual equality in the 1980s, but New Labour brought in gay adoption, an equal age of consent and civil partnerships, and today same-sex marriage commands majority public support. The Tories once condemned Nelson Mandela as a terrorist, but now they call him a saint. I will miss David (pictured) but his departure does not herald the end of New Labour. We had already moved on.

David was a great boss for the 10 very enjoyable minutes that I was a minister at the Foreign Office. Some have charged him with not having the courage to challenge Gordon Brown. That’s not right. The last thing the country (or the party) needed at the time was a bloody leadership tussle, and just as David had turned down the frequently repeated offer of EU High Representative because it would look as if the rats were deserting the sinking ship, so his sense of decency and duty trumped personal ambition.

I hope he’ll return, although the one previous example of an older brother serving in his younger brother’s government was not a great success: the irascible Duke of Newcastle berated his brother Henry Pelham on a daily basis, and when Pelham died in 1754 and Newcastle took over, his premiership was an unmitigated disaster.

Hillary’s star power

While we were at the FCO, Gordon decided, much to the annoyance of everyone, that we should host an Afghanistan conference, in January 2010, with the aim of getting more countries to play their part in the decade-long conflict. In fact, it was a great success, with virtually every major country sending their foreign or defence secretaries and many stumping up extra resources that lightened the load for the UK.

The Prince of Wales hosted a reception at St James’s Palace on the eve of the conference. In a room full of men there were just two women, Hillary Clinton and Cathy Ashton. The men were star-struck, and at one point a line of foreign secretaries turned to the Duke of York and asked him whether he would take a photo of them shaking Hillary’s hand. Rather bemused, the duke obliged.

The not so good Shepherd

This week it was announced that Shepherd’s Restaurant in Marsham Court, which has been a staple of the political diet for 20 years, is closing for good. Shepherd’s stands in a long tradition of parliamentary eating-holes. When the poet Geoffrey Chaucer was an MP, he stayed next door to the White Rose tavern, which was then pulled down to make way for the Henry VII chapel. In the 16th century, there was a trinity of fairly riotous pubs known as Heaven, Hell and Purgatory where you could get a meal. I confess, though, that I never liked Shepherd’s. The menu was stodgy, the service rather self-congratulatory and the private room (where many a plot was hatched) was dingy and musty.

Honesty may not be the best policy

The new citizenship test includes the question: “Who appoints life peers?” Available answers: a) The Queen; b) The Prime Minister; c) The Archbishop of Canterbury; d) None of these. To any student of British politics, this must be a tricky one. True, all the letters patent for new life peers are in the name of the monarch. But nobody really thinks that Her Majesty dreamt up the idea of appointing an extra 122 since the last election, representing one in 10 of all the life peers ever created. She didn’t choose Jeffrey Archer – that was John Major’s idea. So I just hope that nobody fails their citizenship test by giving a truthful answer.

Twitter: @ChrisBryantMP

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments