US glass ceiling shows political cracks

Out of America: Women have been making inroads into positions of power on Capitol Hill, and their fortunes are at an all-time high

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.An unusual thing is about to happen at the highest levels of America's government. Barring an astonishing rejection of his nomination by his erstwhile colleagues in the Senate, an elderly white man of patrician bearing will soon be taking over as Secretary of State. Once, of course, such appointments were automatic. No longer. Today, John Kerry is the exception for a job that for the best part of two decades might have had the sign "women only" posted on the door.

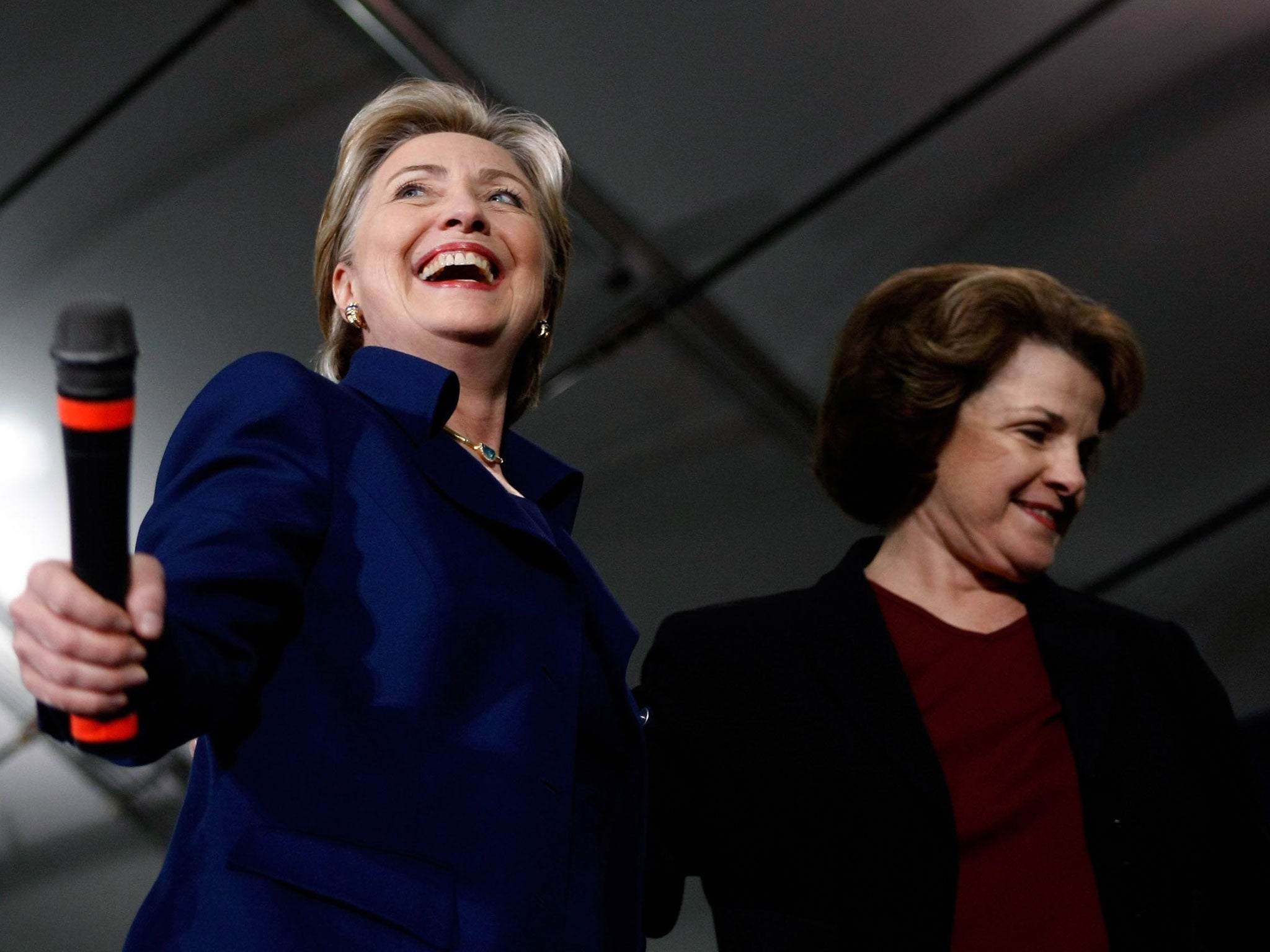

And something of the same is starting to happen on Capitol Hill as well. "Women have the responsibility gene," Hillary Clinton – the most recent of those female secretaries of state – once remarked. In which case, all may not be lost for that feckless and vilified legislature. (It was recently found in an opinion poll here to be even less popular than the notion of the US turning communist. The exact figures, if you're interested, were 10 per cent who approved of Congress's performance, and 11 per cent who looked kindly on a red takeover.)

Although the omens for the 113th Congress which started work last week, are not encouraging, at least the responsible sex is on the march. Of the 535 senators and House members, 101 are women, the most ever. New Hampshire, indeed, has just become the first state to be entirely run and represented by females: the governor, both its senators and two congresswomen.

One way and another, cracks are steadily appearing in the political glass ceiling. It's now almost 30 years since a woman (Geraldine Ferraro, Walter Mondale's running mate in 1984) first featured on a national ticket. And not only have three of the last four secretaries of state been women; in 2007, Nancy Pelosi became the first woman House speaker, third in line to the presidency.

A year later, only the once-in-a-lifetime political meteor named Barack Obama prevented Hillary Clinton from becoming the first female president. Three of the nine Supreme Court justices are now women, while, since September 2011, the most prestigious job in US journalism, executive editor of The New York Times, has been held by a woman. Yet more remarkable, the first ladies were admitted last year as members of that bulwark of southern male obstinacy named Augusta National Golf Club.

Beyond politics, however, women in the US are making slower progress. Take the federal government: lower down the ladder, they are in rough numerical parity with men. But less than a third of the more senior posts – roughly equivalent to the executive grades of the British Civil Service – are occupied by women.

On the corporate front, the picture is even bleaker. Yes, women are advancing, but at a glacial pace. In the workplace, they are paid a quarter less than men for equivalent jobs, while in the boardroom, men still have a stranglehold. Only a tiny fraction of publicly traded American companies are headed by a woman; one in eight don't have a single female board member. Yes, 18 of the Fortune 500 companies are led by a woman, more than ever before. But that's still only 3.6 per cent.

Carly Fiorina summed it up in an interview after she was ousted as CEO of Hewlett-Packard, back in 2005. Ms Fiorina's ascent to the top of one of the country's biggest hi-tech companies was seen as groundbreaking, and she herself hailed it as proof that the glass ceiling existed no more. "Dumb thing to say," she commented drily to Salon.com a few months after her fall.

Not surprisingly perhaps, the US came only 22nd in the latest 2012 ranking by the World Economic Forum of countries, as measured by women's rights and gender equality. The top four places were occupied by the usual Nordic and Scandinavian suspects, while Ireland was ranked fifth. (Britain came 18th.) And even in America's government the ceiling still holds. No part of it has been more unrelentingly male dominated than the national security establishment. Although the Pentagon eased its rules slightly last year, women are still barred from front-line combat. Also, while female secretaries of state have practically become the norm, we have yet to have a woman as Secretary of Defense or director of the CIA. But here, too, things may be changing.

At the Pentagon, the shortlist to succeed Leon Panetta when he steps down includes a woman, Michèle Flournoy. You've probably never heard of her, but in the first Obama administration she held the department's No 3 job, of under-secretary of defence for policy, the highest Pentagon post ever held by a female. With the White House's apparent first choice, the former Republican senator Chuck Hagel, under some criticism, Ms Flournoy could yet find herself Madame Secretary.

True, there's no sign of a lady taking charge of the spies soon. But at the CIA women have long been playing important roles. In the early 1990s, a female counter-intelligence operative named Jeanne Vertefeuille was a key member of the team that exposed the Soviet spy Aldrich Ames as the most damaging mole in CIA history.

And it was a female CIA agent who helped to track down Osama bin Laden in 2011 and serves as model for Maya (played by Jessica Chastain), the central character in the new movie Zero Dark Thirty which recounts the operation. Not least because it suggests that torture – including waterboarding – secured information crucial to pinpointing Bin Laden's hideaway, Zero Dark Thirty has caused a political rumpus. Leading the critics has been the head of the Senate Intelligence Committee, one of the most sensitive positions in Congress – one currently filled by yet another woman, Dianne Feinstein of California.

The biggest glass ceiling of all, of course, is at the White House itself. The US is one of the few major Western democracies never to have had a female head of state or government. (The others are Italy, Spain and Japan.) But even that could change four years hence. Hillary Clinton was released from hospital last week after her blood clot scare. If she wants the job and stays healthy, who'd bet against her in 2016?

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments