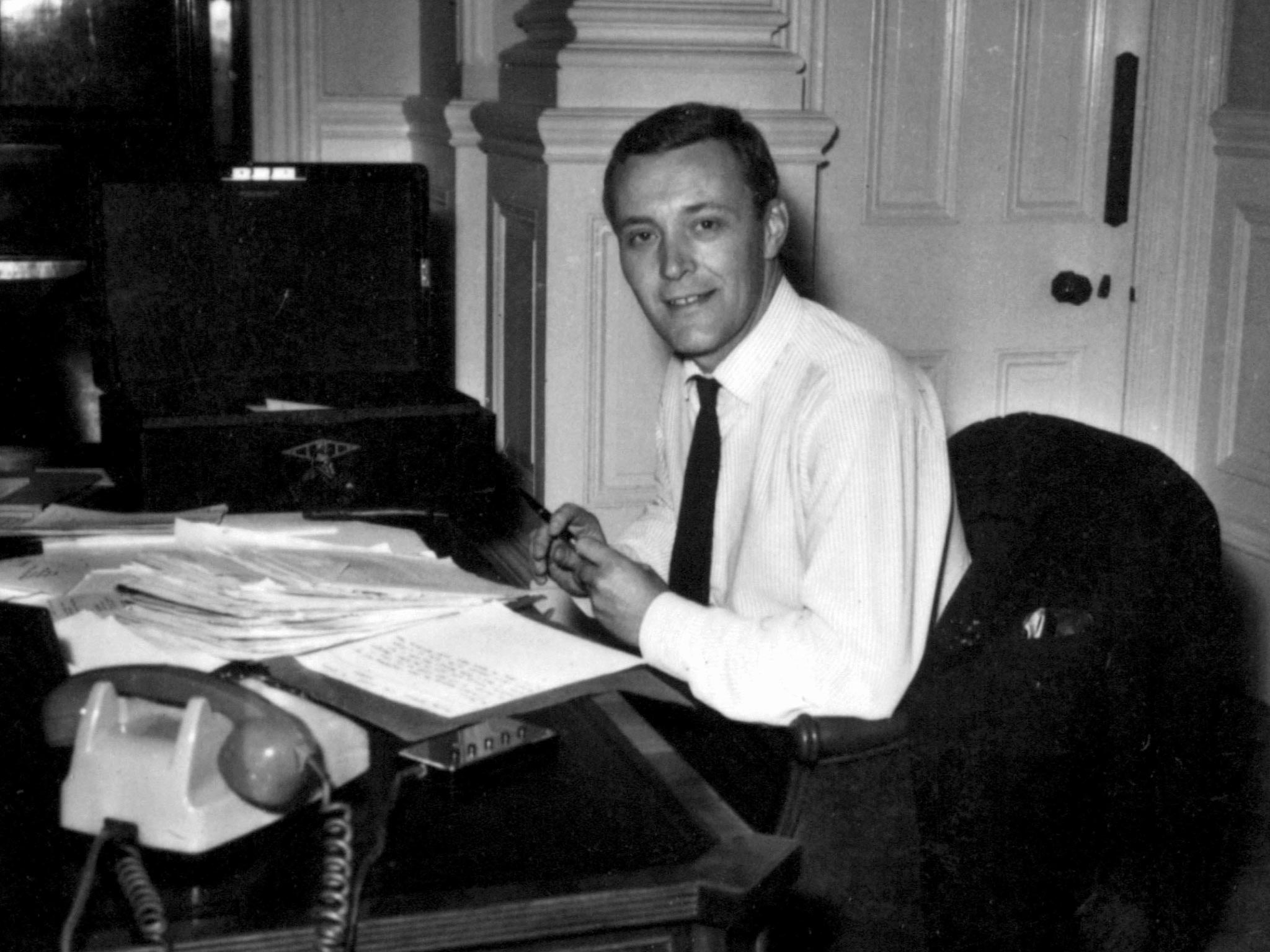

Tony Benn dies: His leadership hopes were foiled by a selection process that favoured compromise

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.There was a time in the late 1970s and early 1980s when the world looked very different, and people took seriously the possibility that Tony Benn could lead the Labour Party and become prime minister.

Most people become more conservative in middle age than when they were young, but Benn seemed to have entered middle age in his 20s, only to break out into youthfulness at the age of 45.

From 1950 to 1970, he was generally a mainstream Labour MP, more interested in new technology than socialism. He did not join the Tribune group, where the Labour left had congregated since the days of Aneurin Bevan, seemingly because it was too left wing. By the time he finally did join, it was not left wing enough and it split, with Benn and his allies marching off to form the Campaign Group, which was so far to the left that even Bevan would have had qualms about signing up.

Rival politicians were puzzled by Benn’s rebirth, wondering whether it was driven by conviction, calculation, or a combination of the two. He was very ambitious and had his eye firmly on the party leadership. Had he stayed in the political mainstream, he would have had to compete with Denis Healey and other heavyweights. If he had moved to the soft left, he would have been up against the mild mannered but very popular Michael Foot. On the outside left, he had no competitors.

On the left there was an expanding political base for him to draw on, as the post-war consensus fell apart in the crisis of the 1970s. With hindsight, we know that the upshot was a long-lasting Prime Minister from the radical right. But Margaret Thatcher was so unpopular during her first couple of years in office that few people expected her to survive the next general election, and it did not seem impossible that the electorate would turn instead to the radical left.

Before Benn could aim for Downing Street, he needed to claim the Labour leadership, which he was never going to do as long as the leader was chosen in a ballot in which only Labour MPs had the vote. When Harold Wilson resigned in 1976, Benn trailed well behind Callaghan, Foot and Healey in the resulting contest.

When the Labour government fell in 1979, he did not compete for a place in the shadow cabinet, instead focusing on his power base in the national executive. The Bennite strategy was to push through changes to the party rules, creating an electoral college through which MPs, constituency parties and unions would all participate in electing the next leader. They were not aiming for one-member, one-vote ballots: it was in the Bennites’ interests that the votes were controlled by the activists.

The proposed rule change was put to the Labour conference but was narrowly defeated when a single delegate from the engineers’ union switched sides. The Bennites then scheduled a special conference for January 1981 to rewrite the rules for electing the leader. Seeing what was coming, Callaghan resigned in 1980 to block Benn’s path by ensuring his successor was elected by the MPs.

Benn did not even contest that election, from which Michael Foot emerged as a compromise leader with Denis Healey as his deputy. Instead, he waited for the rules to be changed, then unilaterally challenged Healey.

The challenge, so narrowly lost, proved to be the high point of the Bennite insurgency. In 1982, Benn and his allies lost their hold over the national executive. The party machine then used a boundary change in Bristol to sideline Benn into a marginal seat, which the Tories won in 1983. It took Benn less than year to get back into Parliament in the Chesterfield by-election, but already there was a sense that his last chance had been lost.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments