This rockonomics world in which we live is unfair and ultimately bad for growth

The top 5 per cent of artists take home almost 90 per cent of all concert revenues

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Last week the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) published its annual statistics on the distribution of income in the UK covering the years up to and including 2011-12. It showed that average incomes fell for the second successive year, declining by 3 per cent at the median and 2 per cent at the mean, after accounting for inflation.

This comes on top of large falls in 2010-11, leaving median and mean income 6 per cent and 7 per cent below their 2009-10 peaks respectively. Mean and median income in 2011-12 is now no higher than it was in 2001-02, after adjusting for inflation.

The falls in incomes during 2011-12 were of similar proportionate magnitude across the income distribution. Income inequality was therefore essentially the same as in the previous year. Rather surprisingly inequality was substantially lower in 2011–12 than it was before the recession. Between 2007-08 and 2010-11, the earnings of lower-income households held up better than those of higher-income households. This is largely because, over that period, real earnings fell whereas benefit entitlements grew roughly in line with prices. However, researchers from the Institute for Fiscal Studies suggest that this reduction in inequality between 2007-08 and 2011-12 will be temporary, and “will have been almost unwound by 2015-16”. This is because if the Office for Budget Responsibility’s (OBR) forecasts turn out to be correct, most of the falls in real earnings had already occurred by 2011-12, whereas a number of cuts to the working-age welfare budget are being implemented over the current parliament. There are likely to be more welfare cuts coming if the Chancellor, George Osborne, has his way, which will worsen inequality still further and falls in real earnings may be greater than the OBR predicts.

Changes in inequality were put in context by Alan Krueger, outgoing chairman of President Obama’s Council of Economic Advisers in a speech last week at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland, Ohio. He colourfully used the example of the music industry, or “rockonomics”, as a microcosm of what is happening in the US economy at large. We are increasingly becoming a winner-take-all economy, and the music industry is an extreme example of a “superstar economy”, he argued.

A small number of artists take home the lion’s share of income. Mr Krueger noted that the music industry has undergone a profound shift over the last 30 years. The price of the average concert ticket in the US increased by nearly 400 per cent from 1981 to 2012, much faster than the 150 per cent rise in overall consumer price inflation. And prices for the best seats for the best performers have increased even faster. At the same time, the share of concert revenue taken home by the top 1 per cent of performers has more than doubled, rising from 26 per cent in 1982 to 56 per cent in 2003. The top 5 per cent apparently take home almost 90 per cent of all concert revenues.

This is an extreme version of what has happened to income distribution as a whole in both the UK and the US. In the US, Mr Krueger points out the top 1 per cent of families doubled their share of income from 1979 to 2011. In 1979, the top 1 per cent took home 10 per cent of national income, and in 2011 they took home 20 per cent. An astonishing 84 per cent of total income growth from 1979 to 2011 in the US went to the top 1 per cent of families, and more than 100 per cent of it from 2000 to 2007 went to the top 1 per cent.

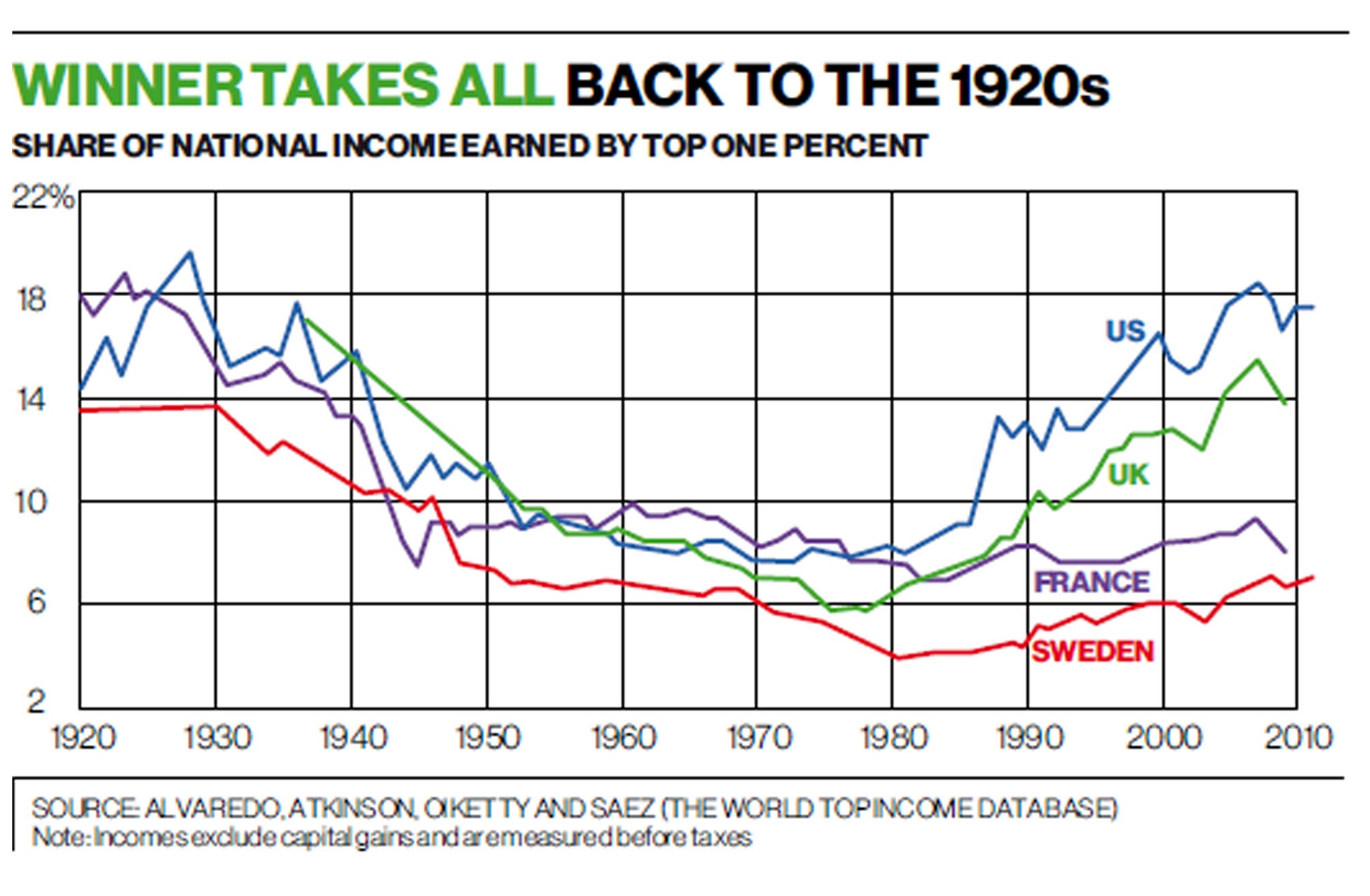

The chart above shows the share of total income going to the top 1 per cent of families starting in 1920 for four countries. During the Roaring 20s, inequality in the US was very high, with the top 1 per cent taking in nearly 20 per cent of total income. This remained the case until World War II. Price and wage controls and the patriotic spirit that “we’re all in it together” during the war caused inequality to fall. Interestingly, the compression in income gaps brought about by World War II persisted through the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s. Beginning in the 1980s, inequality in the US rose significantly with the share of income accruing to the top 1 per cent rising to heights last seen in the 20s.

Inequality followed a broadly similar trend in the UK, France and Sweden, for example. But notice that the level of inequality varies considerably across these countries, and the rise in the share going to the top 1 per cent varies considerably as well. In Sweden, for example, the share of income brought home by the top 1 per cent rose just 3 percentage points, from 4 per cent in 1980 to 7 per cent in 2011, while in the US it doubled from 10 per cent to 20 per cent. In the UK it tripled.

Workers, like music fans, according to Mr Krueger, expect to be treated fairly, and if they perceive they are paid unfairly their morale and productivity suffer. He cites two studies which support this notion. The first study randomly varied the pay of members of pairs of workers who were hired to sell membership cards to discotheques in Germany.

The authors found that increasing the disparity in pay between pairs of workers decreased the productivity of the two workers combined. Their findings suggest that a more equal distribution of wages would be good for business because it would raise morale and productivity.

A second study found that when a business makes the list of the “100 Best Companies to Work for in America” its stock market value subsequently rises by 2 to 4 per cent per year. Because employee morale and compensation are key factors in determining whether a company makes the list, this result suggests that treating workers fairly is in shareholders’ interests.

In another study it was found that in a society where income inequality is greater, political decisions are likely to result in policies that lead to less growth. A recent International Monetary Fund paper also found that more equality in the income distribution is associated with more stable economic growth.

We still aren’t all in this together, but it would be better if we were. We might even get some growth! The Rolling Stones are doing fine; it’s time the average worker did too.

Land of Hope and Dreams: Rock and Roll, Economics and Rebuilding the Middle Class, Alan B. Krueger, Cleveland, Ohio, 12 June 2013

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments