The weird maths that add up to the White House

Out of America: The result is too close to call, and could even be a tie that will make for edge-of-the-seat election viewing

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.You have to admit, first- past-the-post is more fun. Elections decided by direct popular vote and proportional representation may be "fairer" and more "democratic" – but what's an election night when a computer tells you who has won, or how many seats each party will have, within moments of the polls closing?

I have covered elections in France and Germany, Greece and Italy (as well as the Gorbachev-era Soviet Union). But for suspense and great viewing on election night, nothing beats a system when the outcome is determined by a host of separate, winner-take-all contests, as in Britain and the United States. And by any standards, 6 November here promises to be a thriller.

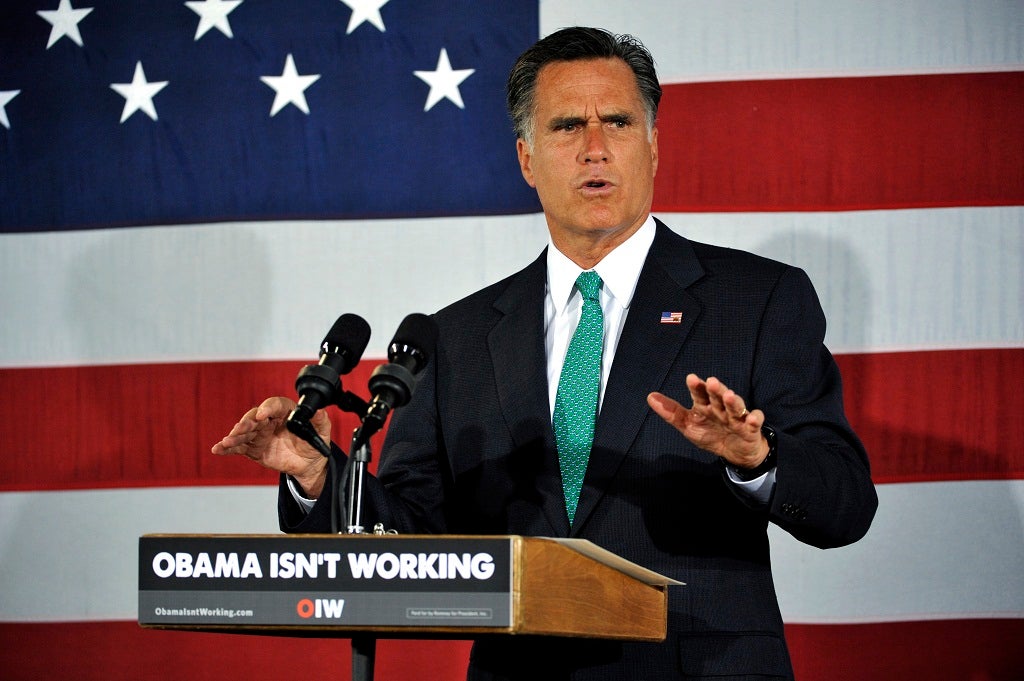

The first thing to remember is that a US president is chosen not in a single nationwide election, but as a result of 51 separate elections in each state and the District of Columbia, in which – as in a British parliamentary seat – a majority is enough for outright victory. Secondly, Americans don't vote directly for a candidate, but for a slate of special electors in each state, chosen by the party. These electors, 538 in number, make up the electoral college that in early January will either re-confirm Barack Obama as the 44th president, or install Mitt Romney as the 45th. Beyond that, everything right now is up in the air.

Landslides of the Eisenhower or Reagan variety are a thing of the past. In the modern polarised and almost equally divided America, 2008 may prove as close as we come – when, in circumstances ideal for a Democrat, Obama won by 53 per cent to 47 per cent in the popular vote, by 28 states (and DC) to 22, and by 365 to 173 votes in the electoral college. By contrast, George Bush's win in 2000 came down to 537 votes in Florida, and just four votes in the electoral college, one more than the minimum needed. Overall, he lost the national popular vote to Al Gore by 544,000 votes. Four years later, had just 60,000 people in Ohio voted for John Kerry instead of George W Bush, Kerry would have become president. This time around could be as close or closer than 2004 – and even more controversial.

Perhaps the electoral college this time will fulfill its most valuable function, translating a narrow edge in the popular vote into a clear majority of electoral votes. But it may not be so simple. Consider a few scenarios. The most straightforward is where a candidate wins the popular vote but is defeated in the electoral college. Even before 2000, that had happened three times. (Britain, incidentally, has had an equivalent experience three times, in 1929, 1951 and 1974, when one party won the most votes, but the other secured the most seats in the Commons so formed the government.)

Were that to happen in nine days' time, the most likely beneficiary would be Obama, on the plausible assumption that he is soundly defeated by Romney in the red states, loses votes in safe Democratic states, but squeaks through in just enough of the hotly contested swing states to win. In that case, justice of a sort would be done, after Bush's win in 2000. There would also be fresh demands that the electoral college be scrapped – but with no greater likelihood of success than before.

More contentious would be a repeat of Gore/Bush, where close results in at least one state or more prompt legal challenges. The Florida impasse 12 years ago came as a shock, but this time both sides are "lawyered up". Indeed electoral litigation, over issues like provisional voting and voter ID requirements, has already far exceeded pre-2000 levels. Any serious dispute is likely to end up in the courts.

Most intriguing of all – and here we're enter the realm of what Italians call fantapolitica – is where one candidate, say Obama, carries the popular vote, but manages only a tie in the electoral college. At that point the election would be decided by the ferociously partisan House of Representatives, where each of the 50 state Congressional delegations would have a single vote. Suppose, for argument's sake, that the Democrats win a tiny overall majority in the House, but 27 of the delegations are majority Republican, and thus supporters of Romney. Obama would be denied a second term by a double distortion, first in the electoral college, and then on Capitol Hill. How would Democrats feel about that?

And the fantapolitica doesn't end there. In the event of a tie, the vice-president is chosen by a simple Senate vote. Imagine the Democrats retain a paper-thin majority in the Senate. Then Joe Biden would be elected vice-president. Welcome to the Romney/Biden administration, truly a match made in heaven.

A tie is extremely unlikely. But not inconceivable. Yes, there are 50 states, but in the vast majority the result is a foregone conclusion. At this stage perhaps only eight, are "in play", visited every other day by the candidates. Of these eight, the most vital is Ohio, and its 18 electoral votes. No Republican has won the White House without it; but without Ohio and Florida (which seems to be edging towards Romney), Obama has virtually no margin for error. But the eight offer various arithmetical paths to a 269-269 split of the electoral college vote.

Arcane stuff, but what excitement it promises on the night. In 1980, Jimmy Carter conceded defeat to Ronald Reagan an hour before the polls had closed on the West Coast. That won't be happening this time. Indeed, we may not know the result until 7 November, or even later.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments