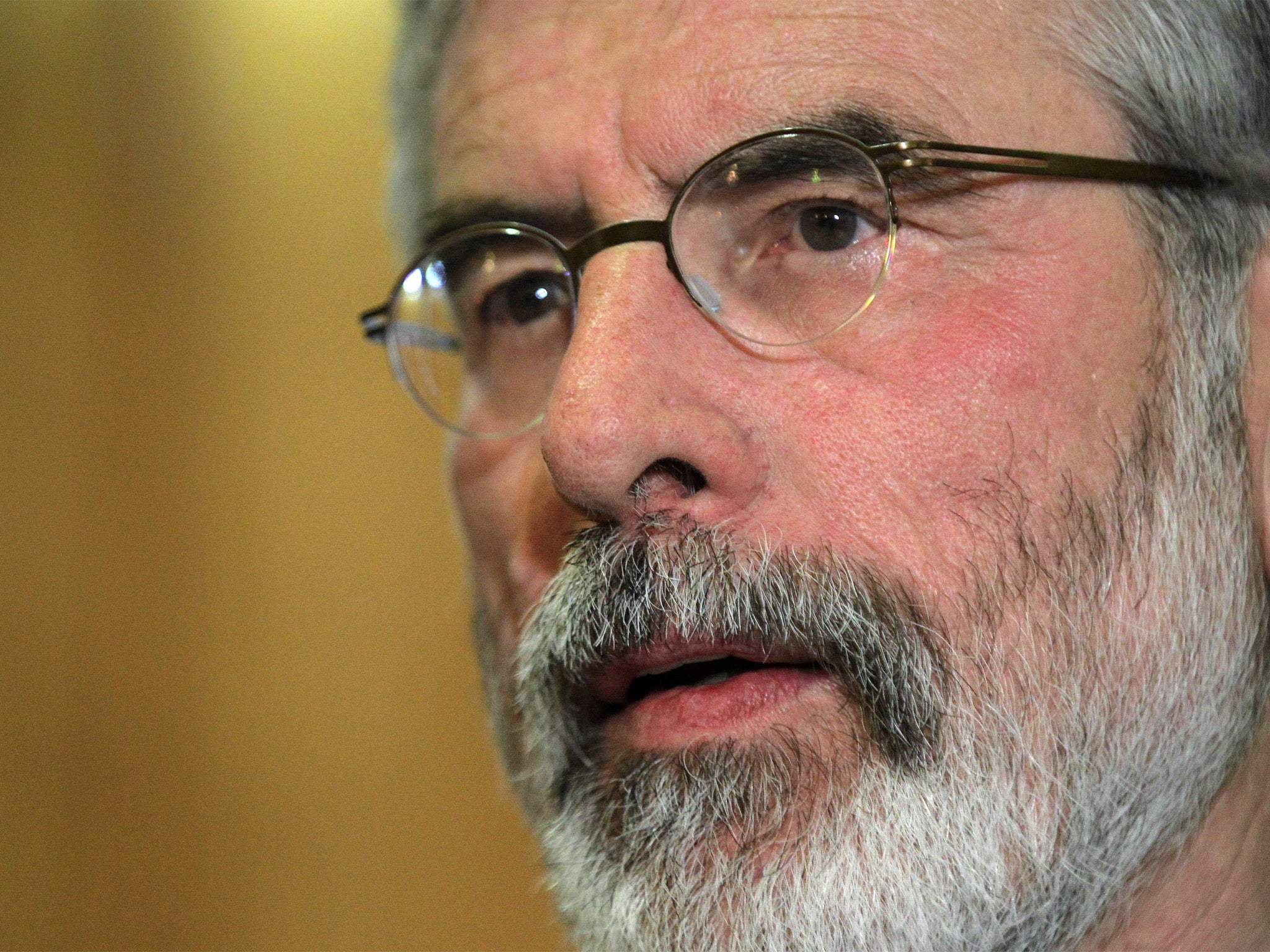

The spread of British hypocrisy, from Gerry Adams and Northern Ireland to Syria

If arresting Adams just before the European elections was not political, then surely the British refusal to inquire into the slaughter in Ballymurphy was.

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The law is the law is the law. So I was taught as a child. But it’s all baloney. Take the case of Gerry Adams, “arrested” and then released after chatting to the Northern Ireland police – I notice the cops did not use the old cliché about “helping the police with their inquiries” – about the torture and murder and “disappearance” of Jean McConville. It is, to quote Fintan O’Toole, that wise old bird of Irish philosophy, “an atrocity that cries out for accountability” – in which Adams has consistently denied any involvement. Sinn Fein announced that Adams’s “arrest” was political, a remark that got the usual tsk-tsk from Unionists and British alike.

But alas, Theresa Villiers, the latest in the hordes of Northern Ireland secretaries to be visited upon Belfast, also announced, a wee bit before Adams’s “arrest”, that there would be no independent inquiry into the killing of 11 unarmed civilians in Ballymurphy in August 1971 by soldiers of the Parachute Regiment, the most undisciplined British military unit to be sent to the province, which later killed another 14 civilians in Derry on Bloody Sunday. In the Ballymurphy shooting, the Brits managed to kill a Catholic priest carrying an improvised white flag and a mother of eight children who went to help a wounded boy. The deaths of Father Hugh Mullan and Mrs Joan Connolly were also deaths that “cry out for accountability”. But of course, there will be none. Ms Villiers has seen to that.

She also ensured that there would be no inquiry into the fire-bombing of the La Mon hotel in 1978, when the IRA burned 12 people to death. Families of the dead have their suspicions that transcripts of police interviews with IRA suspects to this crime were removed from the archives to protect important people involved in the “peace process” in Northern Ireland. No complaints about that, needless to say, from the IRA. But you can see the problem: if arresting Adams just before the European elections was not political, then surely the British refusal to inquire into the slaughter in Ballymurphy – assuming the soldiers involved have not died of old age – was political. After all, the Brits know who these soldiers were, their names, their ages and ranks. They have much more than the statements of two dead IRA supporters – the “evidence” against Adams – to go on.

Now you may argue that the Saville inquiry into Bloody Sunday cost far too many millions of pounds to warrant another investigation into the Ballymurphy deaths. But then you may also ask why the soldiers who gave evidence to the original inquiry were given the cover of anonymity. This was something Gerry Adams was not offered – nor, given the favourable political fallout, was he likely to have asked for it. But then it would also be pleasant if the Brits who know something about the Dublin and Monaghan bombings during the worst days of the Irish war could pop over to Dublin and give a little evidence about this particular atrocity. No chance of that, of course.

And you don’t have to stick in Ireland for further proof of legal hypocrisy. Take our beloved Home Secretary’s decision to deprive British immigrants of their British passports if they go to fight Assad’s regime in Syria. Quite apart from the fact that William Hague, the Foreign Secretary, and his friends originally supported the armed Syrian opposition, there are problems with the passport story. Many British supporters of Israel, for example, have fought on Israel’s behalf in Israeli uniform in that country’s wars. But what if they served in Israeli units known to have committed war crimes in Lebanon or Gaza? Or in the Israeli air force, which promiscuously kills civilians in war. Are they, too, to be deprived of their passports if they were not born in the UK? Of course not. One law for Muslims, another for non-Muslims – not unlike Spain’s offer of passports to the descendants of those driven from their homes in the 15th century, a generous act somewhat damaged by the fact that only Jews (not Muslims) may take advantage of it.

We will not dwell upon all the other hypocrisies of the Middle East – the outrage at any Iranian interest in acquiring nuclear weapons, for example, when another country in the region has an awful lot of nuclear weapons; or US fury at Russian annexation of Crimea but no anger at all about the annexation of Golan or the theft of Arab land in the West Bank, which are equally illegal under international law. Upon such foundations is aggression built: the illegal invasion of Iraq, for instance.

I contemplate all this because of a little research I’m undertaking about a Moroccan air force colonel who, in 1972, tried to stage a coup against the brutal King Hassan who was also, by the way, quite an expert on “disappearances”. Mohamed Amekrane flew to Gibraltar and threw himself upon the dodgy mercy of Her Majesty. He pleaded for asylum (after all, the coup had failed) but we packed him off back to Morocco because, while the European Convention on Human Rights gives anyone the right to leave his or her own country, no international treaty obliges a country to give that person asylum. So back Amekrane went – and was, of course, put to death. His widow eventually got £37,500 from the British government – ex gratia, needless to say, out of goodwill not guilt, you understand – and Colonel Amekrane was then erased from history. Interesting to see what happens to the ex-Brits who lose their passports for going to Syria – and have to go back to the country of their birth. They might be better off – and live longer lives – if they to go off to fight in another jihad.

The Great War’s forgotten victims in the Levant

Horrors of the Great War you will not read about this year: among the casualties were another million dead, the men, women and children of the Ottoman Levant – for which read modern-day Lebanon and Syria – who died of famine, victims of both the Allied blockade of the east Mediterranean coastline (which is why we ignore these particular souls) and of the Turkish army’s seizure of all food and farm animals from the civilian population; all this in addition to the million and a half slaughtered Armenians of 1915. Many Lebanese remember parents who ate nettles to stay alive, just as the Irish did in the famine. I have a book by Father Antoine Yammine, published in Cairo in 1922, illustrated with photos of stick-like children and of a priest in his habit lying dead on a Beirut street, another of a baby suckling at his dead mother’s breast outside their front door. “And some there be which have no memorial; who are perished as though they had never been…”