The quest for meaning and the desire for tribalism

It’s not difficult to understand the historic need for religion

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Thank you for your overwhelming response to last week’s column asking “which God” would allow incidents such as the shooting down of flight MH370, the protection of some would-be passengers and not others, and the deaths of innocent Palestinian children in the Gaza conflict?

I had admitted that, search as I might, the answer to these questions is not evident to me in any religion - neither the one in which I was brought up (Catholicism) nor another. As ever, having ventured into this territory, some readers accused me of having “a closed heart” – when my entire point is that my heart and head are open, but they are simply not finding any answers, other than that humans need to be less inhumane to each other.

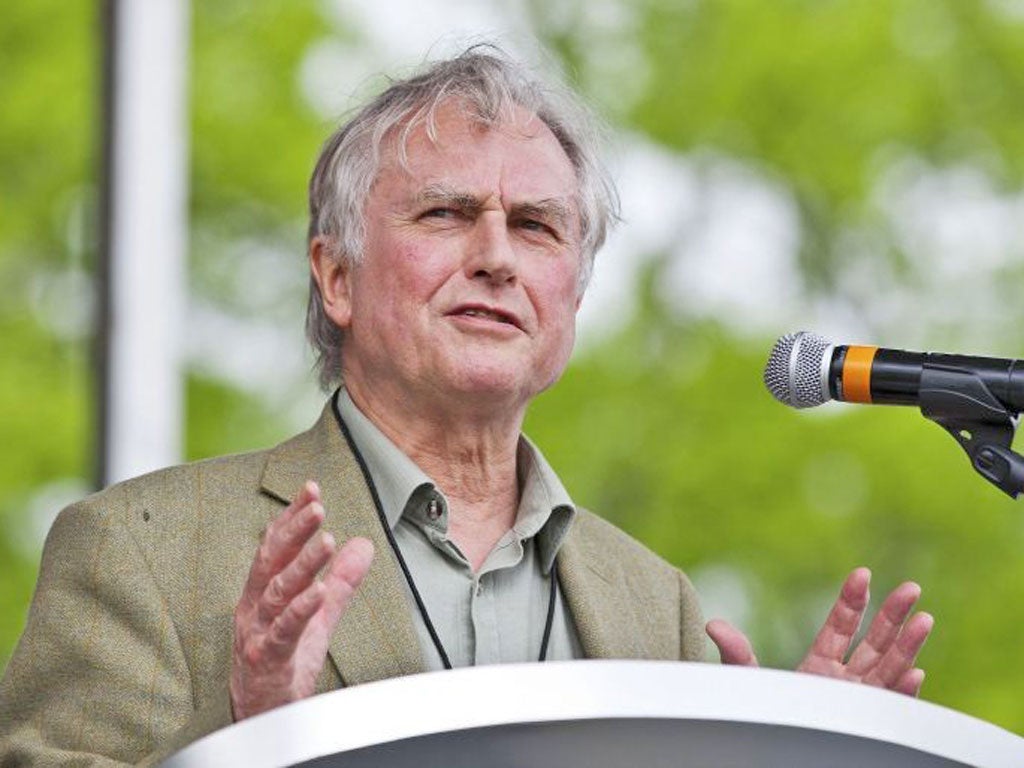

Richard Dawkins is a polarising figure, but at the weekend a series of his tweets caught the eye: “I don't hate Muslims. I don't hate Jews. I hate the hereditary mental illness called religion which labels targets of hate in Palestine” was one of four such tweets about different global conflicts, including ISIS and Iraq.

It’s unfortunate and self-defeating that Dawkins used the term “hereditary mental illness”, because changing those words to “hereditary belief systems” would have had greater long-term meaning, if not short-term shock value.

It’s not difficult to understand the historic need for religion: the quest for meaning on one hand and the desire for tribalism on the other have been with us since the coming of man. That search for meaning has led to so many false idols and fables becoming “God” and the “holy word”. That need to huddle together in tribalism is still evident everywhere from Amish communities to pop “fandoms” and football supporters. The need to collectively believe in a supreme being is an inevitable consequence of these primeval instincts.

Being more cynical, one might buy into the famous Marx quotation: “religion is the opium of the people”. While it’s true that Marx was articulating his belief that religion was a way of “power” saying “don’t worry if you’re downtrodden in this life, you will find a reward in the next”, in the wider quotation from which those words are taken, he was actually being more sympathetic: acknowledging the potential of religion to give solace where there is distress.

That’s how I feel when I look on in bemused fascination at members of my own family’s religious devotion despite their never-ending series of trials in this life. As a callow, arrogant youth I would try the Marx line out on them, only to be dismissed. And rightly so, because back then I was merely trying to provoke them.

Today, the conversation is different. I respect their beliefs because I can see the solace they have brought them, whilst absolutely rejecting any attempts to continue to force those beliefs upon others, or to marry them to the state.

The need for complete dis-establishment of church and state not only in this country, but in all countries, appears so obvious in the face of the many inequalities that accompany “establishment” that it is mystifying that in the 21 Century that there can be any argument against it. But then, what do I know? Apparently, my heart is closed.

Stefano Hatfield is editorial director of High50.com

Twitter: @stefanohat

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments