The Coalition has failed the young - but a tax cut from George Osborne could help

These are likely to be the lost generation. Long spells without work leave scars

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The unemployment rate ticked down to 7.6 per cent this month, much to my surprise. It’s down from 7.9 per cent when the Government took office in May 2010. The number of unemployed however, is down by a paltry 5,000 in three years, from 2,471,000 to 2,466,000 in the most recent data.

But one group has seen a marked worsening in their labour market conditions all across the country since this Government took office, and its situation was dire already, and that is the young. There were 929,000 unemployed youngsters under the age of 25 in May 2010 compared with 965,000 today. The unemployment rate of 16-17-year-olds has risen from 33.5 per cent to 36.2 per cent and from 17.8 per cent to 19.1 per cent for 18-24-year-olds. The bad news is getting worse for the young.

There is considerable variation in youth unemployment rates by region, but they have risen across the country. For example, unemployment rates for 18-24-year-olds are currently 26.1 per cent (up from 19.7 per cent in May 2010) in the North-East and 26.3 per cent (18.2 per cent) in the West Midlands, compared with 18.2 per cent (15.6 per cent) in the South-East.

Few if any of these kids are going to be able to participate in the Help to Buy scheme. Not too many of the 18-20-year-olds on the youth sub-minimum wage of £5.03 or the £3.72 under-18 rate or the apprentices’ rate of £2.68 or even at the adult minimum wage of £6.31 an hour will be able to participate either.

In part, this rise in youth unemployment occurred because of the closure of both the Future Jobs Fund and the Educational Maintenance Allowance that were abolished by the Coalition. It said these schemes didn’t work, but this was apparently based on dogma rather than fact. Subsequently, a survey commissioned by the Department for Work and Pensions showed the exact opposite, proving the schemes were hugely successful, providing strong, positive rates of return. Nothing the Coalition has introduced since then appears to have worked, hence the job market for the young has worsened.

We also know that the young are faced with a double whammy. Even if they have a job, they are more likely to be underemployed than any other age group. Even if they have a job, they are disproportionately likely to hold a temporary job but would like a permanent one. They are also more likely to be forced into taking a part-time job rather than a full-time one. My recent work with David Bell also shows that the young would like many more hours while those over the age of 50 would like fewer.

Of particular concern is the number of 18-24-year-olds who have been continuously unemployed for at least a year, which is up from 187,000 in May 2010 to 256,000 today. There are 54,000 youngsters age 18-24 who have been claiming benefits continuously for a year or more, up from 28,000 in May 2010. The main reason this should concern everyone is that these are likely to be the lost generation, as we know long spells of unemployment when you are young cause permanent scars. They lower the chances of being employed later in life; it is crucial to get a toehold in the labour market. If a youngster doesn’t, they never catch up. Shamefully, we are three years in and have seen no improvement.

One response I frequently receive when I write about the problem of youth unemployment is that the initial rise occurred under the previous Labour government. David Cameron has been fond of using this kind of blame game to wriggle out of taking responsibility for a youth joblessness disaster.

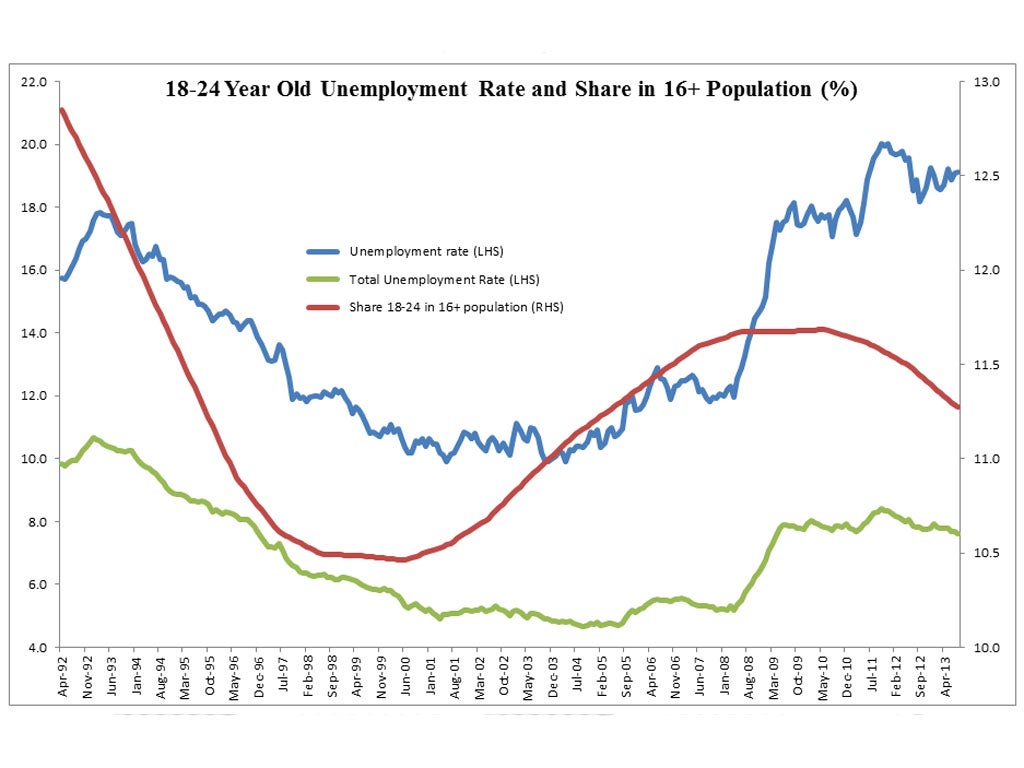

The data tell a rather different story as illustrated in the chart (below). This plots on the left-hand axis the youth unemployment rate, which fell steadily through 2004 to around 10.5 per cent, tracking the overall rate, which hit 4.7 per cent. But then youth unemployment started to rise steadily, even though the overall rate stayed broadly flat. The reason for that is due to a rise in the size of the cohort, which is also plotted on the graph. From around 2000 to 2008 the share of those aged 18-24 as a proportion of the 16-plus population rose by a full percentage point from 10.5 per cent to 11.5 per cent and then fell back.

It seems youth unemployment grew from 2000 to 2008 because of a rise in labour supply. Since then, it has increased because of a fall in labour demand. Politicians need to recognise these facts before trying to make cheap political points.

The Office for National Statistics this week published a new study on graduates in the UK labour market, which showed that even new graduates are struggling. They examined recent graduates and non-graduates aged 21 to 30, and found that the recent graduate group had consistently lower unemployment rates. Since the 2008-09 recession, unemployment rates have risen for all groups but the sharpest increase was experienced by non-graduates aged 21 to 30. None of the groups has seen unemployment rates fall back to their pre-recession levels. Overall, 41 per cent of all employed graduates in the UK were working in public administration, education and the health industry. In contrast, only 22 per cent of employed non-graduates were working in these sectors.

This means that public-sector job cuts, and hence lack of hiring, have especially impacted the young. The proportion of recent graduates who were employed in jobs that do not normally require knowledge and skills developed on a university degree course has risen from 37 per cent in May 2001 to 47 per cent in May 2013.

I understand that the Chancellor is looking into the possibility in his Autumn Statement of scrapping National Insurance for employers who hire youngsters, which would give a relative boost to the hiring of the young and stimulate the economy.

Great idea. I have long advocated this reform, which has generated cross-party support. I am with George Osborne on this one but I would extend it to every employed youngster under 25, not just to new hires.

Almost a million young people are out of work. One might ask: why has it taken so long?

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments