This recovery is the slowest for at least a century – so why do rates have to rise?

Economic View: Many will point to what they call strong growth or a buoyant labour market

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.If you talk to economists in the financial markets, the only way UK interest rates will go in the near future is up. Many have been saying the first increase will come in a matter of months – and some have been saying the same thing for over a year.

Members of the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) have generally been more cautious but they, too, have indicated that the next interest rate move, whenever it happens, will definitely be up. I think they could be making a very costly mistake.

The facts on the ground do not point to a rate increase. Inflation has in effect been zero since the beginning of the year. When it is stuck at 2 per cent below the Bank’s target, it is an odd time to be thinking about raising interest rates. Of course, one important reason why inflation is so low is the collapse in oil prices, but core inflation – a measure that strips out volatile elements such as energy prices – has been bobbing around 1 per cent since the beginning of 2015, so this is still well below target.

Many will point to what they call strong growth or a buoyant labour market. In reality recent growth has been mediocre. Looking at the raw growth figures is misleading, because they are flattered by high inward migration; migrants are if anything more likely to be working after they arrive than those already here. A better measure to look at is output per capita (output divided by the total population). Since the beginning of 2013 this has only been growing at an annual rate of around 2 per cent, which is very slightly below typical UK growth rates.

Yet in a recovery, output per capita should be growing at well above average rates. In these terms the current upturn is extremely disappointing. It is the slowest recovery from a recession for at least a century. That, of course, is not how the Government likes to describe it, but it is very worrying that much of the media follows the Government in failing to point out how disappointing current growth is. This might be excusable if we knew for certain that rapid growth was just around the corner, but as recent events in China show, this is far from the case.

Unemployment has fallen rapidly in recent years, but the latest figures suggest that may have come to an end, at a level which is above the trend before the financial crisis.

Nominal earnings growth has picked up a little in recent months, which might suggest some tightening in the labour market. But it could just be that productivity has at long last started growing again. If wages and productivity growth continue to move together, there is no additional pressure on prices.

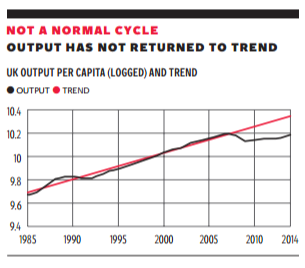

I suspect one reason everyone is thinking about a rate increase is that this is what normally happens at this stage in what economists call the business cycle. When output falls, rates are cut to boost demand; when output starts recovering, rates should start to rise. But one thing we can say with absolute certainty is that this has not been a normal business cycle. The chart plots the log of output per capita against a simple trend that assumes growth of around 2.25 per cent a year, which was around the average from 1955 to 2008.

Growth in the first decade of the last Labour government was, if anything, slightly above this trend. Then we were hit by the financial crisis. After previous UK recessions, like those in the early 1980s or 1990s, output started to return to the pre-recession trend – but that has not happened this time. We are still a massive 15 per cent below the historic trend.

We know that one reason why the recovery faltered from 2010 to 2012 was fiscal austerity. The Office for Budget Responsibility estimates (somewhat conservatively) that fiscal retrenchment reduced growth by 1 per cent in both of the first two financial years of the coalition government. However, it seems improbable that this explains the whole gap between where we now are and the pre-crisis trend.

There are two types of story you can tell. One is that there has been a quite extraordinary and unique decline in the ability of UK companies to produce goods, which represents a permanent loss in capacity. Survey evidence, for what it is worth, backs this up. In those circumstances, thinking about raising rates makes some sense. The second possible story is that deficit demand is stopping us getting back closer to the pre-crisis trend.

The financial markets and the MPC think the first story is more likely, and they may well be right. But that misses the point. As no one has come up with plausible explanation for why we have lost so much potential output (which is why it is called the “productivity puzzle”), there has to be a significant chance that the second story might be correct. Even if we are now only 5 per cent below where output could be without risking excess inflation, that represents a huge loss of resources – something close to £1,500 for every adult and child in the UK each year.

Good policy should not just look at the most likely outcome, but also at risks. At the moment there is a significant risk that we may be losing a huge amount of resources because of a tepid recovery. To cover that risk, we should cut rates now. The worst that can happen if this is done is that rates might have to rise a little more rapidly than otherwise in the future, and inflation might slightly overshoot the 2 per cent target. Inconvenient, but not very costly.

If we fail to cover that risk, there is a non-trivial probability that in three years’ time inflation will still be well below target and we will all be asking why on earth everyone in 2015 was talking about an interest rate increase.

Simon Wren-Lewis is professor of economic policy, Blavatnik School of Government, University of Oxford

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments