Rupert Murdoch should have been on trial, not his hacks at The Sun

The journalists who were charged and acquitted were part of a culture where any story could be bought, but they didn’t invent it

Support truly

independent journalism

Our mission is to deliver unbiased, fact-based reporting that holds power to account and exposes the truth.

Whether $5 or $50, every contribution counts.

Support us to deliver journalism without an agenda.

Louise Thomas

Editor

When four Sun journalists were acquitted last Friday of corruptly paying public officials for stories, they were not just relieved. They were also very angry. For they had been shopped by their own employer, News International.

In grave trouble itself, the company had given selected emails and expenses documents to the Metropolitan police. As one of the journalists facing charges told the court: “I couldn’t believe I had been handed over to the police by the company where I have worked loyally for 27 years.” In answer to questions from his lawyer, he went on: “I felt completely betrayed by the company. They were not prepared to protect me and they were not prepared to protect my sources.”

That is why, for me, the true villain in this story is the high command of News International itself. It was from there that the pressure came that landed the Sun journalists in court long before emails and documents were handed over to Scotland Yard. However, some newspapers have cast the case in a different light. They blame the Government and argue that the Sun journalists were subject to a show trial.

I agree that the default position of the government of the day, and of the police, will always be to bottle up the press whenever there is an opportunity. For instance, it was recently revealed that the police had been deliberately misusing anti-terror laws to get hold of journalists’ phone records in an attempt to discover the identities of their sources. And the press’s vulnerability resulting from the phone hacking scandal certainly provided as good an excuse as any.

Since 2011, 100 journalists have been arrested or interviewed under caution. Thirteen have been convicted, mainly in connection with phone hacking. In addition, police bail has been extended with the result that many journalist suspects have been left in a state of cruel uncertainty for over three years. When they say that this is the equivalent to a living nightmare, I am sure they are right. Indeed I have no doubt that the police have seized their chance to intimidate the press. But the case of the Sun journalists wasn’t a show trial. After all, the defendants were acquitted.

The reality is that juries find it difficult to handle trials that involve the public’s right to know. Last Friday’s acquittals were not the first. In November, a former journalist for the Sun, Clodagh Hartley, was cleared of illegally paying a press officer for information including details of the March 2010 Budget. Then a month later, another Sun reporter, Nick Parker, was cleared of aiding and abetting misconduct in a public office.

There are many difficulties in assessing the rights and wrongs of paying pubic officials for information. The Daily Telegraph paid £150,000 in order to acquire full details of MPs’ expenses and there was no fuss about that.

Here are some of the grey areas. Quite often, for example, the transaction is initiated by a public official, who contacts a newspaper and offers information in return for a payment. One of the journalists in the dock told the court that, to begin with, he was concerned about the idea of paying a serving police officer but his mind was set at rest after speaking to an in-house lawyer. He said he was advised that this would not amount to corruption because the PC had approached The Sun first. I am not sure that is right.

Then, what if the information that was purchased would have quickly become public anyway – so that the newspaper was, in effect, doing no more than hurrying things along? When The Sun bought and published information from an official at Broadmoor high-security hospital to the effect that Peter Sutcliffe, the so-called Yorkshire Ripper, had been assaulted with a knife, the court was told that such an incident would rapidly become the “talk of Broadmoor and the two pubs at the bottom of the hill… Something like this would not stay secret for very long.” In such circumstances, the jury must have wondered what the harm was.

A third hard case is when the informant is essentially a whistleblower who would like to be paid for his or her pains. An example relating to a Thames Valley hospital was given in court.

So what were the factors that contributed to landing the Sun journalists in court in the first place? One was the pressure to perform that is a feature of a wide range of organisations these days, whether commercial or not. But in the case of the Sun newsroom, there was a particularly disagreeable version.

A news editor informed the court that “on occasions you would receive 25 emails of an extremely unpleasant nature from Rebekah Brooks” in a morning. The court was also told that nobody at The Sun queried payments being made to public officials. It was common knowledge inside the newspaper that cash was handed out in return for supplying information. No executive was ever upbraided for making the payments. As counsel for the prosecution put it, The Sun’s “journalistic culture” involved the use of “wheelbarrows of cash to obtain stories, irrespective of the source.” Counsel told the jury: “It was a culture in which cash was king. Everything and everyone had a price. The story was all. The ends justified the means”.

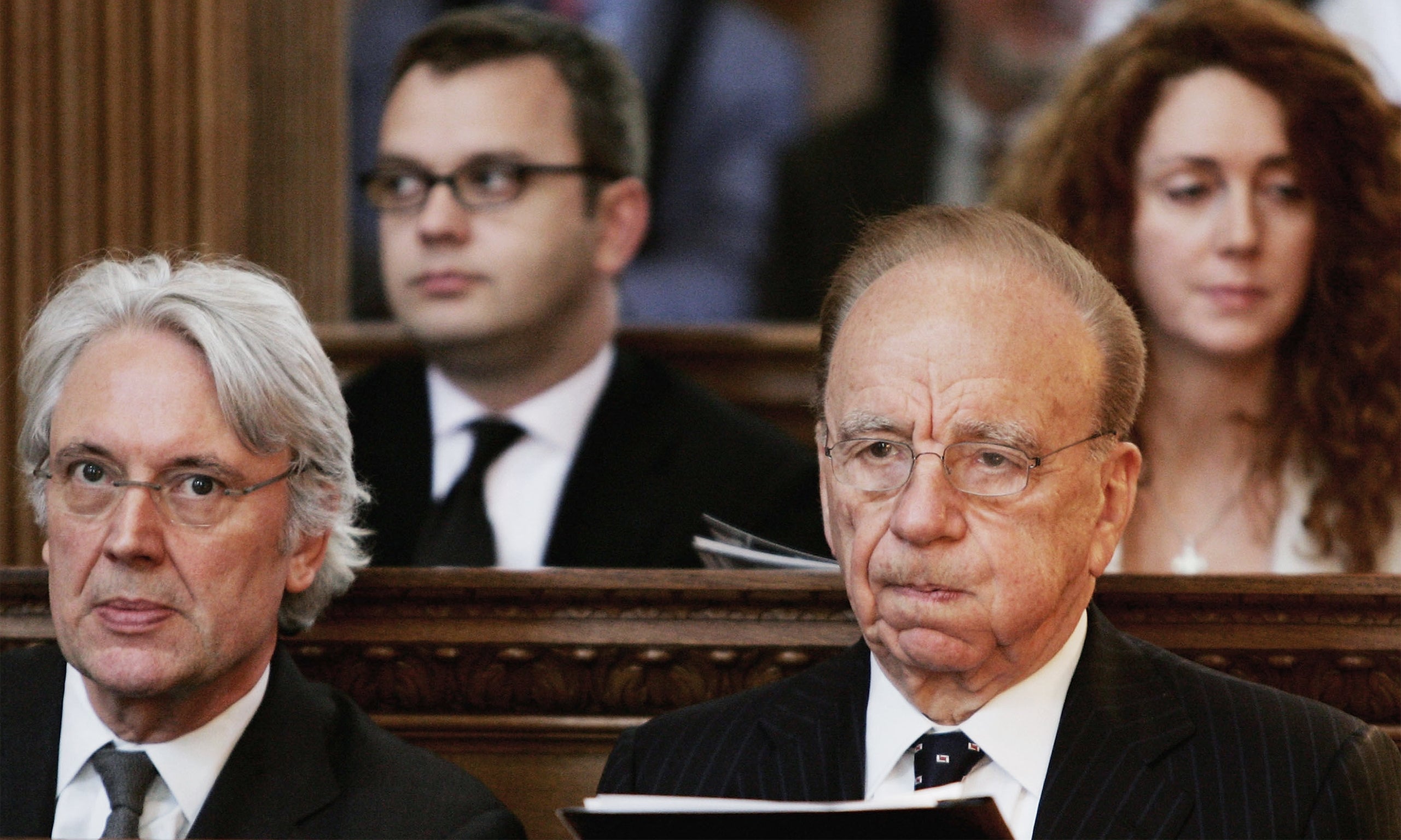

The journalists who were charged and acquitted were part of this culture, but they didn’t invent it. The jury seems instinctively to have realised that. They must have thought, as I do, that the wrong people were facing charges. For the infallible rule where the ethos of organisations is concerned is that, for better or worse, the culture is always set at the very top, by the boss. In the case of The Sun, that person is Rupert Murdoch. He is responsible for the behaviour of his staff and should personally pay any penalty that becomes due.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments