MPC’s downgrade shows it is too early to raise rates

Latest forecasts are likely optimistic, given the euro area’s downside risks

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.I was in Switzerland last week – an intriguing place most of us know for little except making watches and knives with oodles of blades whose purpose remains unclear.

I’ve been racking my brains to come up with famous Swiss people, without much success: the economist John Kenneth Galbraith once said that the only two Swiss that anyone has ever heard of were Calvin, who was French, and William Tell “who had a somewhat perilous attitude to parental duty”.

But the performance of the Swiss economy stands in stark comparison with that of the UK. Since the start of 2008, Switzerland has grown 5.2 per cent compared with a decline of 3.2 per cent in the UK. Unable to raise interest rates above zero for fears of derailing the economy, the Swiss National Bank has been forced to rein in house prices by raising the capital it requires banks to hold against mortgages. This follows its capping of the Swiss franc against the euro in September 2011. These kinds of unconventional policies should be on the table for consideration when the regime changes at the Bank of England in July.

That brings us to the latest forecast of the MPC which, as expected, contained gloomy news of Britain’s economic prospects and in particular higher inflation. It should be said, though, that a good chunk of this inflation – amounting to 1 per cent of the present 2.7 per cent – is because of what the committee calls administered prices, those which are affected by government or regulatory decisions and not from demand pressure so should be ignored in setting monetary policy. A good example is tuition fees which the MPC expects to contribute around 0.3 percentage points to Consumer Price Index inflation throughout next year and 2015.

Most embarrassingly, though, the MPC once again downgraded the growth forecast in its 20th-anniversary Inflation Report.

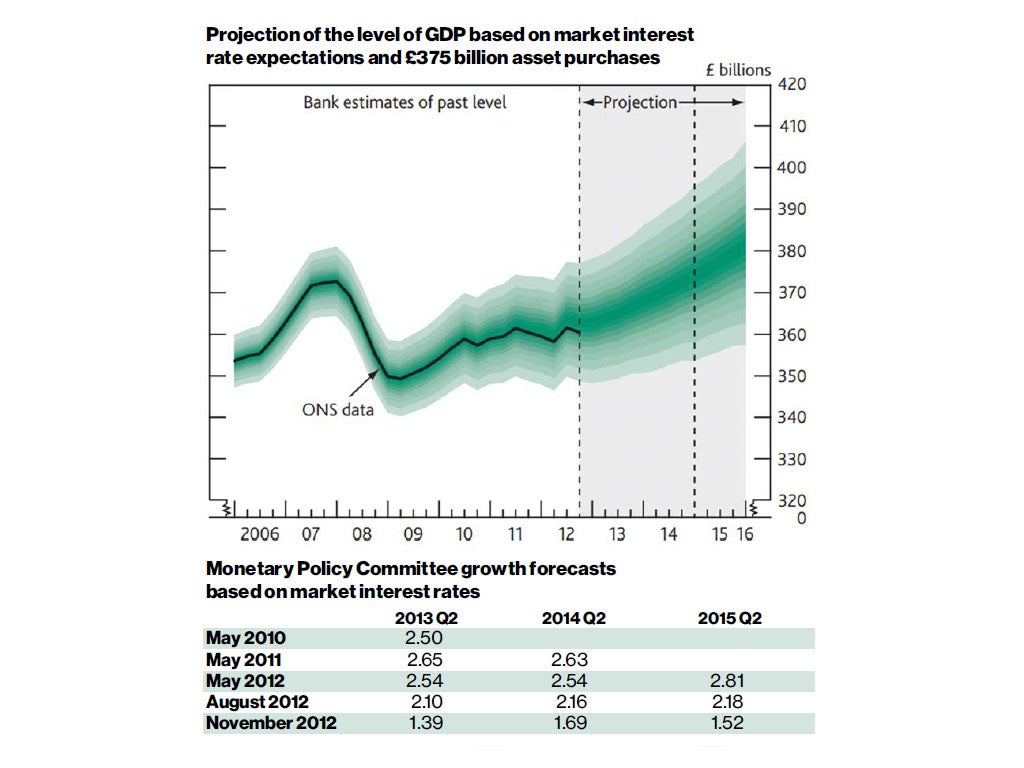

The UK economy is going nowhere and even the latest forecasts are likely overly optimistic, given the still substantial risks to the downside from the euro area and not least because small businesses remain capital constrained. Take a look at the fan chart, which is constructed so that outturns are expected to lie within each pair of the lighter green areas on 10 occasions. In any particular quarter of the forecast period, GDP growth is expected to lie somewhere within the fan on 90 out of 100 occasions. And on the remaining 10 out of 100 occasions GDP growth can fall anywhere outside the green area of the fan chart. The fan suggests that growth around election time in 2015 will be in the interval of 4.5 per cent at best and minus 1 per cent at worst with the so-called central projection around the probably unreachable 2 per cent. Even this bullish forecast implies the level of output at the start of the recession will not be restored for seven years, making this the weakest recovery in more than a century. Interestingly the MPC does not share the view of the make-believe recession deniers that GDP growth will be revised up significantly. The black line to the left of the vertical dotted line is the official ONS forecast and the fan around it is the “backcast”; the fact that the green area above the line is roughly the same as the green area below it means that the MPC believes the chances that the data will be revised up are approximately the same as the chance it will be revised down.

The chances are that even this forecast will be revised down as almost all the previous ones have been. The table sets out the MPC’s growth forecast for the second quarter this year, next year and in 2015. The first forecast for this year’s second quarter was made in May 2010 and, as time moves on, a quarter is dropped and a new one added. For some strange reason it doesn’t publish the most recent exact numbers in the current forecast for a while, so they have to be interpolated off the chart with a ruler and pencil. It looks like the latest forecast for last year’s second quarter is around 1 per cent and for this year around 1.5 per cent – well below the forecast the MPC made of 2.54 per cent for both only nine months ago.

I was also struck by one highly hawkish and false claim in the Inflation Report: “The amount of downward pressure that those seeking jobs place on wages is likely to diminish the longer they have been unemployed, as their skills erode.” There is no evidence that the long-term unemployed impose any less pressure on wages than do the short-term unemployed. Wages remain the dog that hasn’t and isn’t going to bark.

It makes sense that the MPC, just like the Swiss National Bank, continues to ignore any suggestion that it should tighten monetary policy any time soon. Perhaps those who want to raise rates should spend a little time at altitude to get them back to the real world where ordinary people live.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments